In Conversation with Andrea Gibson

Billy Lezra

coco aramaki

I was stuck in a bus during a decimating New Jersey winter the first time Andrea Gibson spoke to me through my right headphone (the left one was broken). The poem was grief and glory in the same breath; it was called “Dive.”

(excerpt)

and the second time’s a lie

I love you

I love you

see what I mean

I don’t

and I do.

And I’m not talking about a girl I might be kissing on

I’m talking about this world I’m blissing on

and hating

at the exact same time

see life

doesn’t rhyme

it’s bullets

and wind chimes

it’s lynchings

and birthday parties.

You’ve described your writing process as bizarre—that the poem moves through the body; the words reveal themselves last. How do the words actually come to you?

I write out loud running around the house. I’m hyper-focused on sound, how the words sing and how truthfully they make their way into the air. Something can feel honest on the page, and then when spoken they can reveal themselves to be less than authentic. So that’s what I keep touching back to, feeling for what is true. I typically begin by asking myself what needs to be said, and the answer more often than not surprises me, as what needs to be said is quite commonly a secret we are keeping from ourselves.

In “Dive,” how did you land on “bullets/wind chimes/lynchings/birthday parties”?

That piece I wrote mostly while running through a field. I was jogging one day and heard the most heartbreaking sound of my life. I started running in the direction of the sound and ended up at a “branding day celebration” which sadly, is an actual thing—a day when baby cows are branded and people hang out and drink and BBQ and party while watching the whole awful scene. The sound I heard was not the cries of the baby cows being pinned down and branded, though that was itself excruciating to listen to, but the sound of almost 200 adult cows, who had run from every corner of the pasture, to try to bust down the fence to save their babies from the violence. I don’t know if I’m answering your question, but in the moment I arrived there I was struck by the horror and the love all at once, how all of it is happening at the same time everywhere, and that’s when the poem started making its way into the air.

william dibble

In what ways does performing the same poem over time change the meaning of the poem for you?

The same way a poem means something different to different individuals, the poem means something different to me each time I read it, as I am forever growing, changing, and becoming. I have a heart rule in which I promise myself I won’t perform any poem I can’t in that moment resonate with. And that rule often ensures that I will read poems I’m not expecting to read each night, so to make sure to stay true.

You’ve said that you would only write love poems, if you could have it your way; that writing a love poem about a woman is political in itself. You put out “Hey Galaxy” as a response to the political climate, despite having just written an album full of love poems. How would you describe your personal and creative trajectory between “Hey Galaxy” and “Right Now, I Love You Forever”?

I delayed the love album because of the election of Trump, which, when I write that down-seems like the wrong decision, doesn’t it? Delaying love because of Trump? It felt right at the time. There were things I needed to scream about. We were all altered by a fascist becoming president, and still are. That said, there is a line in the new show that says “How will we ever achieve world peace if we can’t figure out how to sew a white flag our of our bedsheets?” That one line drew me back to the idea and then, as I began writing, I realized nothing doesn’t intersect with love. The show talks about climate change, suicidality, chronic illness, queer rights, most of the things I talk about in other shows—except this time it is all written through a lens of love.

Where do you go to find inspiration?

Everywhere. There is no place I don’t find it.

What is the best piece of creative advice you have ever received?

Write what you are most terrified to write.

How do you know when a poem is done?

When I read it out loud to an audience and nothing feels unnecessary, or absent.

How would you like to be remembered?

I would like to be remembered as an awfully good person, and as a goodly awful person, meaning I’d like to be remembered as a whole person who cared about other people’s wholeness.

Where do you go to find hope?

My girlfriend wrote a poem in which she said “the most beautiful word in the English language is stay.” For me, all of my hope is found in staying with whatever comes up. If there is joy I stay as presently as I can possibly stay with that joy. If there is grief I stay as presently as I can possibly stay with that grief. To not run away from is where I find hope. Or life. To not run away from is where I find life.

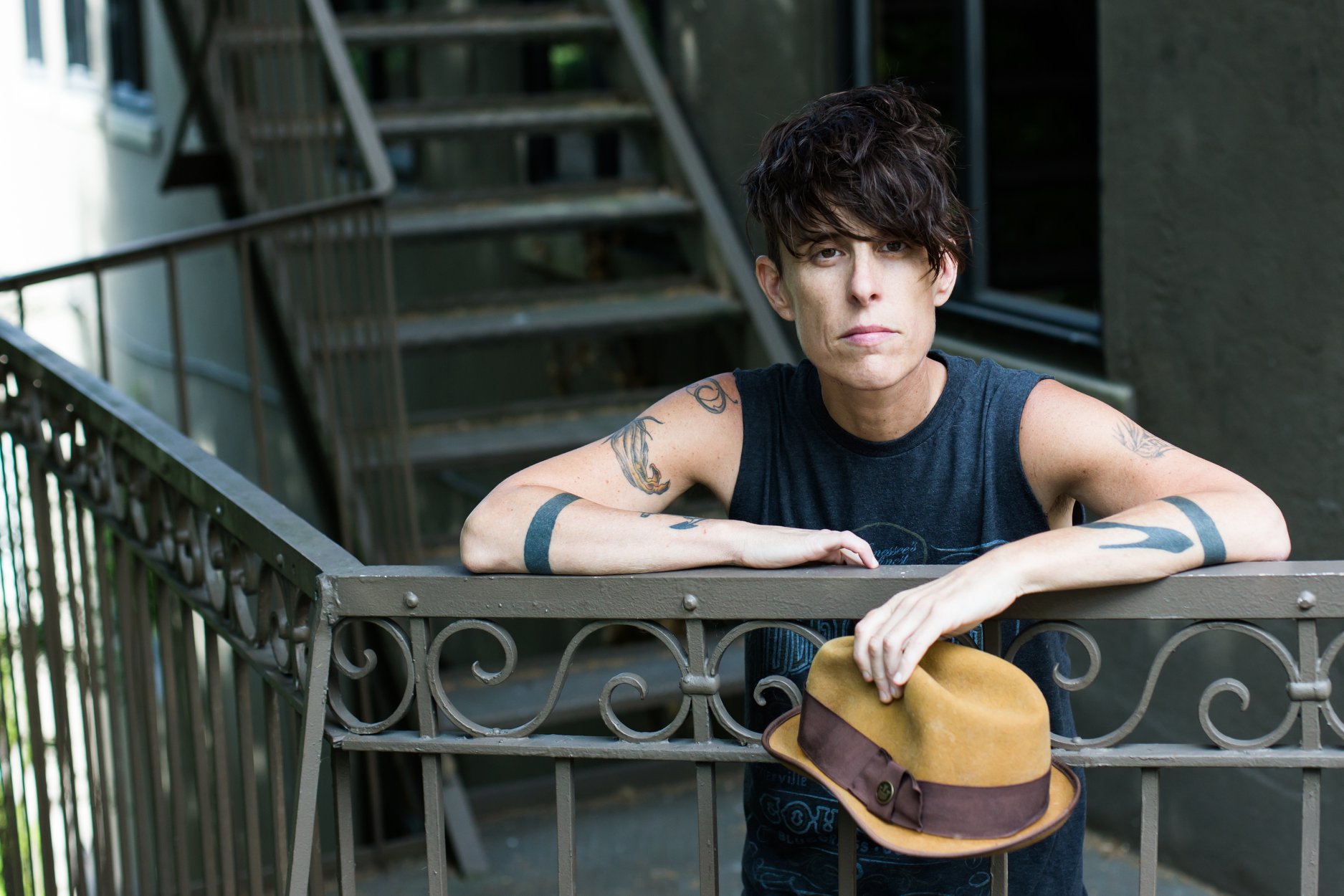

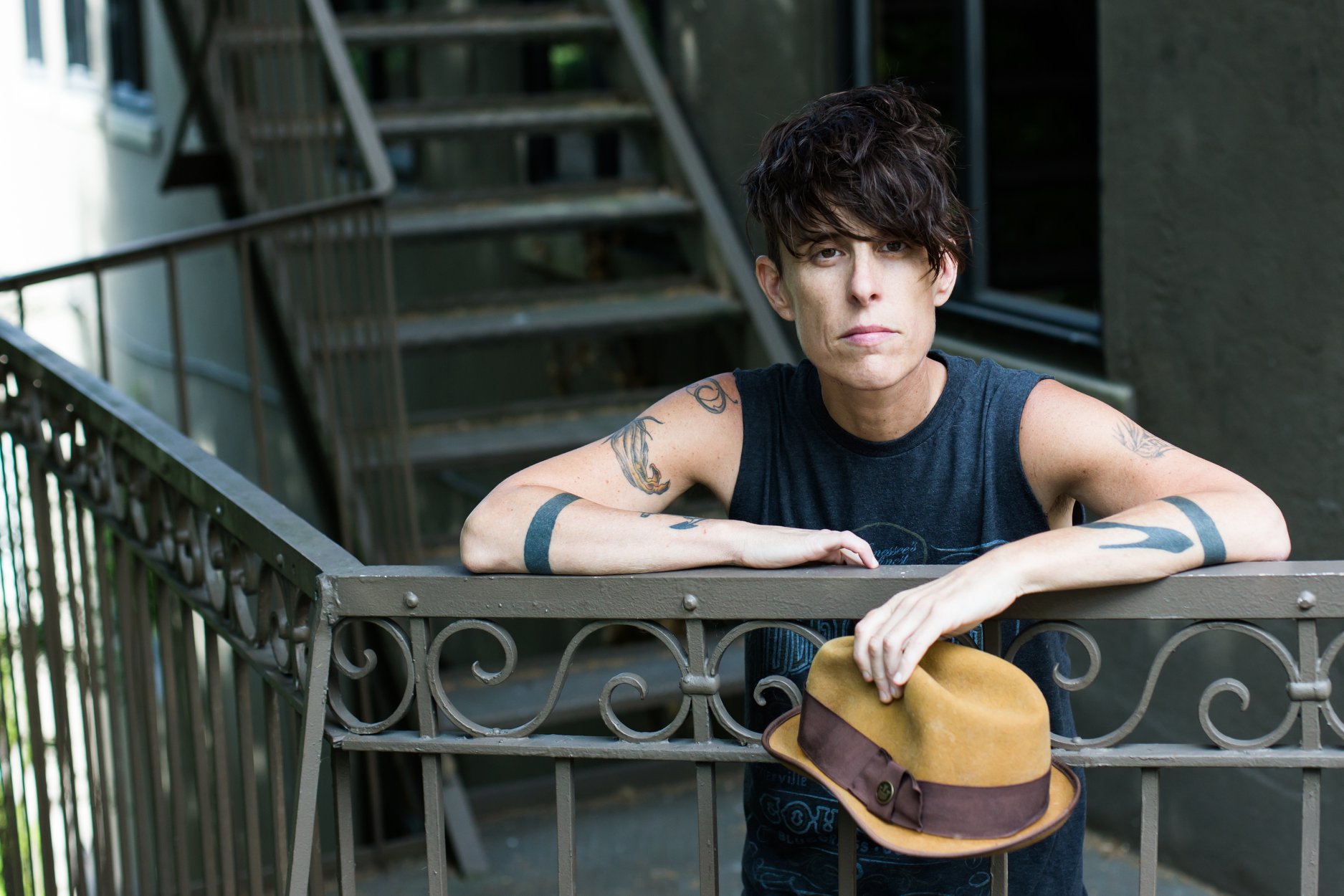

Andrea Gibson is an award-winning poet and activist born in Calais, Maine.

Their Facebook page (with over 116,000 followers) describes their illustrious career: They began performing in 1999 with a break-up poem at an open mic in Boulder, Colorado. Gibson then leaped into the forefront of spoken word poetry on the national scene in 2008 when they won the first-ever Woman of the World Poetry Slam. Author of three collections of poetry and currently working on an illustrated collection of their most memorable quotes for Penguin (Winter 2018), Andrea (they/them/their) has also released seven (7) full-length albums.

They are currently touring their newest album: Right Now, I Love You Forever. The show is “a multimedia, poetic story-telling experience” highlighting “the most unforgettable moments of their love-life: from a neighbor’s pet pig walking in during a sexy hook-up, to being proposed to just hours after leaving the psych ward.”

annie schugart

In Conversation with Andrea Gibson

Billy Lezra

coco aramaki

I was stuck in a bus during a decimating New Jersey winter the first time Andrea Gibson spoke to me through my right headphone (the left one was broken). The poem was grief and glory in the same breath; it was called “Dive.”

(excerpt)

and the second time’s a lie

I love you

I love you

see what I mean

I don’t

and I do.

And I’m not talking about a girl I might be kissing on

I’m talking about this world I’m blissing on

and hating

at the exact same time

see life

doesn’t rhyme

it’s bullets

and wind chimes

it’s lynchings

and birthday parties.

You’ve described your writing process as bizarre—that the poem moves through the body; the words reveal themselves last. How do the words actually come to you?

I write out loud running around the house. I’m hyper-focused on sound, how the words sing and how truthfully they make their way into the air. Something can feel honest on the page, and then when spoken they can reveal themselves to be less than authentic. So that’s what I keep touching back to, feeling for what is true. I typically begin by asking myself what needs to be said, and the answer more often than not surprises me, as what needs to be said is quite commonly a secret we are keeping from ourselves.

In “Dive,” how did you land on “bullets/wind chimes/lynchings/birthday parties”?

That piece I wrote mostly while running through a field. I was jogging one day and heard the most heartbreaking sound of my life. I started running in the direction of the sound and ended up at a “branding day celebration” which sadly, is an actual thing—a day when baby cows are branded and people hang out and drink and BBQ and party while watching the whole awful scene. The sound I heard was not the cries of the baby cows being pinned down and branded, though that was itself excruciating to listen to, but the sound of almost 200 adult cows, who had run from every corner of the pasture, to try to bust down the fence to save their babies from the violence. I don’t know if I’m answering your question, but in the moment I arrived there I was struck by the horror and the love all at once, how all of it is happening at the same time everywhere, and that’s when the poem started making its way into the air.

william dibble

In what ways does performing the same poem over time change the meaning of the poem for you?

The same way a poem means something different to different individuals, the poem means something different to me each time I read it, as I am forever growing, changing, and becoming. I have a heart rule in which I promise myself I won’t perform any poem I can’t in that moment resonate with. And that rule often ensures that I will read poems I’m not expecting to read each night, so to make sure to stay true.

You’ve said that you would only write love poems, if you could have it your way; that writing a love poem about a woman is political in itself. You put out “Hey Galaxy” as a response to the political climate, despite having just written an album full of love poems. How would you describe your personal and creative trajectory between “Hey Galaxy” and “Right Now, I Love You Forever”?

I delayed the love album because of the election of Trump, which, when I write that down-seems like the wrong decision, doesn’t it? Delaying love because of Trump? It felt right at the time. There were things I needed to scream about. We were all altered by a fascist becoming president, and still are. That said, there is a line in the new show that says “How will we ever achieve world peace if we can’t figure out how to sew a white flag our of our bedsheets?” That one line drew me back to the idea and then, as I began writing, I realized nothing doesn’t intersect with love. The show talks about climate change, suicidality, chronic illness, queer rights, most of the things I talk about in other shows—except this time it is all written through a lens of love.

Where do you go to find inspiration?

Everywhere. There is no place I don’t find it.

What is the best piece of creative advice you have ever received?

Write what you are most terrified to write.

How do you know when a poem is done?

When I read it out loud to an audience and nothing feels unnecessary, or absent.

How would you like to be remembered?

I would like to be remembered as an awfully good person, and as a goodly awful person, meaning I’d like to be remembered as a whole person who cared about other people’s wholeness.

Where do you go to find hope?

My girlfriend wrote a poem in which she said “the most beautiful word in the English language is stay.” For me, all of my hope is found in staying with whatever comes up. If there is joy I stay as presently as I can possibly stay with that joy. If there is grief I stay as presently as I can possibly stay with that grief. To not run away from is where I find hope. Or life. To not run away from is where I find life.

Andrea Gibson is an award-winning poet and activist born in Calais, Maine.

Their Facebook page (with over 116,000 followers) describes their illustrious career: They began performing in 1999 with a break-up poem at an open mic in Boulder, Colorado. Gibson then leaped into the forefront of spoken word poetry on the national scene in 2008 when they won the first-ever Woman of the World Poetry Slam. Author of three collections of poetry and currently working on an illustrated collection of their most memorable quotes for Penguin (Winter 2018), Andrea (they/them/their) has also released seven (7) full-length albums.

They are currently touring their newest album: Right Now, I Love You Forever. The show is “a multimedia, poetic story-telling experience” highlighting “the most unforgettable moments of their love-life: from a neighbor’s pet pig walking in during a sexy hook-up, to being proposed to just hours after leaving the psych ward.”

annie schugart