The Past is as Fluid as the Future

In Conversation with Susan Stryker

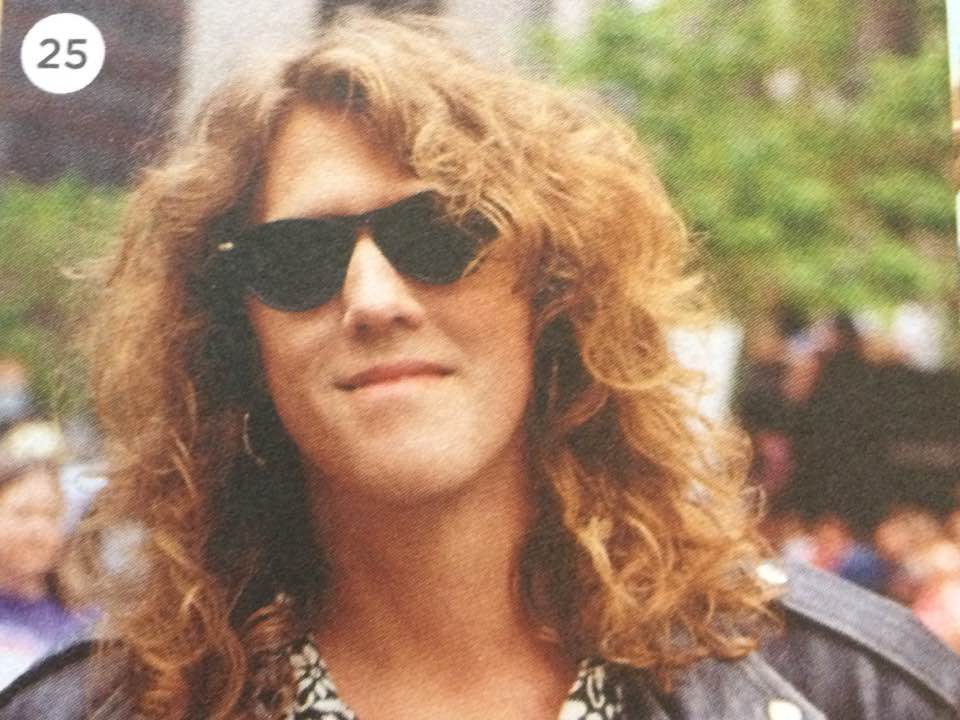

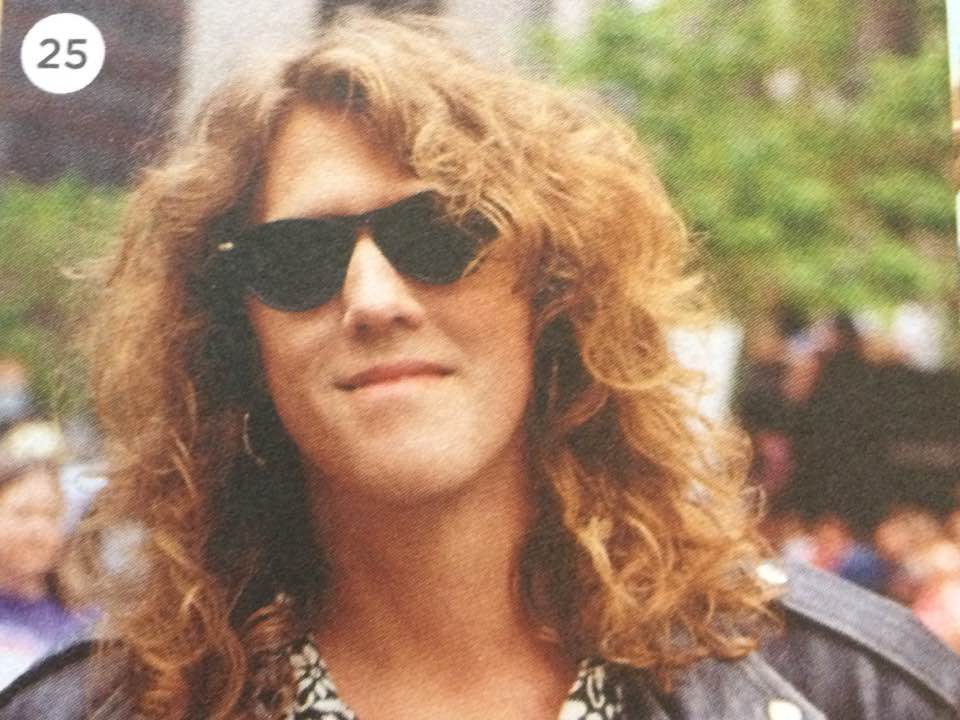

This photo was taken for a Tucson Weekly story about the trans studies initiative at University of Arizona. The backdrop is the courtyard of the Gender & Women’s Studies building.

Susan Stryker, who received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, and completed her postdoctoral research at Stanford, is a pioneer in the field of transgender studies. Before her appointment at Mills, Professor Stryker held appointments at Harvard, Yale, University of California, Santa Cruz, and Simon Fraser University. Susan Stryker is Professor Emerita of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona, and Barbara Lee Distinguished Chair in Women’s Leadership at Mills College. According to Inside Higher Ed, she is “a driving force” in expanding academic programs and faculty hiring for transgender studies.

Also a longtime award-winning activist, author, and filmmaker, Professor Stryker is co-founder of direct-action activist group, Transgender Nation, and executive director of San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society, 1999-2003. She is co-founder of the TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, the first academic journal in the humanities and social sciences devoted to exploring transgender issues through an expressly interdisciplinary lens. Prior to this, Professor Stryker was among the first openly transgender authors to ever publish an academic article in a peer-reviewed journal.

Interview by Billy Lezra and Liam Lezra | October 12, 2020

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How are you?

In general? Same crises as everybody else. Not necessarily the same boat, but the same storm. There’s the COVID pandemic, the public health crisis, the economic crisis, the crisis of democracy in the U.S. The forests are burning here in California, the air has been unbreathable. The seas rise, the glaciers melt, the hurricanes rage and the deserts creep. You know, just the usual, right? But at an individual level, I live a relatively privileged life. I have a comfortable place to live, a salary for the time being, I eat well, I get enough sleep, I exercise regularly, I stay hydrated. I’m fine. The people closest to me are fine. As long as the whole social system doesn’t collapse, I’m as good as anybody could reasonably expect to be.

How did you decide to become a professor?

I come from a working class, rural, southern white background. I didn’t come from a family that had a lot of access to higher education, but I was groomed in this upwardly mobile way that encouraged me to go to college. For the longest time, I really thought I would go into medicine. That would be a good job that I could get if I had a good education. Besides, I was fascinated with bodies.

But what I realized as soon as I got to college was that I hated my science classes. They seemed dull to me, too mechanistic, like they already had all the answers to all the questions. I realized—this is how I formulated my dissatisfaction in my eighteen year old brain—that I was not interested in how bodies functioned, but rather in what bodies meant. That was a humanities question, not a science question. It had never dawned on me that you could go to college to study the humanities. I switched degrees from Zoology/Pre-Med to Letters after my first semester as a freshman, and never looked back.

The Letters major at the University of Oklahoma where I went to college on scholarship was really cool. You had to have upper-division concentrations in Philosophy, History and Literature, plus three years’ study of a one modern and one classical language, fines arts appreciation and history of science, and a minor; I minored in Economics. I was also in the honors program, which meant that instead of big mass lectures, I got to take small seminars with professors for all of my core classes. It was like I discovered a secret small little liberal arts college hidden inside the machinery of Big State U.

After I shifted gears, I had no idea what I was going to do for a career. I never wanted to be an elected official, but I thought I’d be really a good policy wonk on a campaign, or a strategist. I was active in student government. Then between my sophomore and junior years I interned with the Oklahoma State Senate Legislative Research Office and decided that there was no fucking way was I going to go into politics.

My junior year, it was like, Ding, Ding, Ding! I really enjoy being in college—I should become a professor! That still promised the class mobility I associated with being a medical doctor, but with the bonus of stay in college for the rest of my life and getting to think about the things I think are interesting.

What are you interested in thinking about?

I’m interested in interpretive questions. Part of what makes history interesting to me is that it sits on that boundary between empirical evidence—the material trace that an event has left in some record—and the creativity of storytelling. There’s a common but misguided assumption that the past is fixed in place and we just have to recover knowledge about it somehow. That a fact that happened, we will learn about it, and then we will know what the past means.

But I find the past to be in many ways as fluid as the future. There is always a speculative dimension to recovering the past. That doesn’t mean you can just make stuff up, history is at some level a practice of truth-making, but the truth of the past isn’t fixed or predetermined. The past is a foreign country in some ways, where you find things that you weren’t expecting based on their difference from present-day understanding. I think that’s actually the politically radical promise of studying history: that it empirically documents the actual existence of a social order different from now. And just as the past is different from now, transpositionally, the future can be different from now. Ultimately, history bears witness to the inescapability of difference and the inevitability of change. That’s hopeful for all of us who feel oppressed by the current organization of the world.

How did you decide to pursue a Doctoral Degree at UC Berkeley in United States History?

Based on my undergrad Letters major, I thought I should pursue my “good job” in either History, Philosophy, or Literature. At the time, I considered literature to be limited to questions of representation, and philosophy to questions about ideas and concepts. I thought of History, on the other hand, as the study of all human culture in the contexts of time and place. Why not swing for the fences? But then to narrow that vastness down, I had to answer the question of “history of what?” And I decided on U.S. history, since that’s where I’m from. Like my earlier interest in bodies that I was pursuing through medicine, my interest in history was largely rooted in questions about myself as a trans person. In hindsight, I can see that I was first asking questions about “how can my body be like this, and my identity be like that?” and later asking questions about how identities always emerge in specific historical circumstances that provide their “conditions of possibility.” But all along my “research” was based on “me-search” at some level. How was it possible that a person like me existed?

When I graduated from college in 1983, there were actually really poor prospects for getting a professorship, given that all the Baby Boomers already had tenure in those sorts of jobs and were still a long way from retiring. So I decided to apply to only the most highly rated History programs, figuring if I could get in I’d stand a good chance of landing one of a small number of available jobs. If it didn’t work out, I was planning on being a bartender and working on a novel.

I applied to Berkeley, Harvard, Yale, Michigan and North Carolina, which at the time were rated the top five history programs by the American Historical Association. I got into Berkeley, Michigan and North Carolina. Berkeley was actually my number one choice. Growing up mostly in Oklahoma but having lived in Europe and the Pacific because my father was in the Army, I knew there was a wider world I wanted to move in. When I was a kid, I always said I wanted to live someplace that other people go to on vacation. And when I saw San Francisco on television and thought, “That’s a really beautiful, interesting city by an ocean. That could be a good place to live.” Then Harvey Milk was assassinated my junior year of high school. I thought that if a gay person could be elected to citywide office in San Francisco, that must mean that there are a lot of gay people in San Francisco, and that it might be a good place to be trans. And then, to top it off, I learned that Berkeley was right across the Bay from San Francisco. I was very inspired in the student movements of the sixties, and knew Berkeley was where the revolution was happening. The thought of being in that milieu was really exciting. Getting into Berkeley felt like winning the lottery. It was a beautiful place to go and become radically queer.

What did you write your dissertation on?

The origins of Mormonism. Think about it: in 1825, there is no such thing as a Mormon. They don’t exist. The name has not been invented. No Mormon walks the face of the earth. It’s just not a thing yet. Twenty years later, in 1845, there’s a new church, there’s a new body of sacred literature, there’s a new cosmology, there are new forms of kinship, there’s transcontinental migration; there’s an anti-Mormon backlash. A new identity and community formation simply erupted onto the stage of history in very short order. I wrote about Mormonism as a case study in the formation of marginal cultural identities. It was kind of a crypto-trans project, written at a time when it was not possible to study trans history more directly. I never published that work, but what I learned about the process of sociogenesis during my Ph.D. studies informs everything I’ve done since.

What did you do when you finished your doctoral program?

I’d been aware of my trans feelings since early childhood, but it wasn’t until I was in my later 20s that my dysphoria was so strong that I simply had to transition, no matter the consequences. It was hard. I was married, and that blew up. It was virtually impossible to be taken seriously for professorial jobs as an out trans person. It was virtually impossible to be taken seriously for any job at all—employment discrimination against trans women is a very, very real thing. I was dirt-poor, trying to pay off student debt. I was living in a collective household in Oakland with a motley crew of anarchist, queer folks who were ten years younger than me. I had to hustle, making money however I could. I’ve called the period after I finished my Ph.D. my seven year unpaid residency in transgender studies.

I’ve often said that there’s only one job most trans women are allowed to have, and that’s to figure out how to get other people to pay you for being a trans woman. I decided to do that by using my historical training to learn and teach about trans history. That’s going to be my shtick, the thing I knew how to do, that felt live “right livelihood,” whether or not it actually paid the rent. The 90s were a hard decade for me. There was a real sense of financial deprivation. I made less money than I was making as a graduate assistant. I hovered around ten thousand dollars a year for seven years, living in the Bay Area which is not cheap. I would not have made it without my community.

I felt like I won the lottery again in 1998 when I was awarded a Ford Foundation/Social Science Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship that let me study history of sexuality at Stanford for a couple of years. It was like forty thousand dollars a year, which was four times what I had been living on. But it was also a huge validation for the grass-roots work I’d been doing on trans history, a big stamp of approval and recognition from the powers that be. Plus I now had enough money to complete my medical transition. My life changed a lot in 1998.

How did you become the Executive Director of the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco?

I had been involved with the Historical Society since ’91, when I was just coming out as trans and finishing my Ph.D. I started as a volunteer. Then I was asked to join the board of directors, and I became very involved with the organization. It was a real base of operations for me as I delved into trans history. By 1998, when I got the post-doc at Stanford, the organization was kind of falling apart during in the first wave of the dot-com boom. Our rent was about to triple. Nobody in the organization had any real experience with fundraising or organizational development. Things could have simply collapsed. But since I had some new-found income through my post-doc, I said: “Let me become the organization’s executive director”—we’d been an all-volunteer group with no paid staff—“and I’ll do it for a stipend”—I think I said $5000—“but if I can raise the money we need to keep the doors open and pay real staff salaries, then when my post-doc runs out I want to be hired half-time with healthcare benefits.” I thought it would be a great day job, that would let me continue with my research. So that’s what the organization did, I think mostly in desperation. And that’s when I found out that I could raise significant amounts of money. During my “unpaid residency” I had learned how to hustle and sniff out opportunities that nobody handed to me.

What was your path to becoming a professor?

By the mid 2000s I’d written some academic articles that were retroactively positioned as foundational to the emerging field of transgender studies. I had written a couple of coffee-table books on queer history, as well as the first edition of my Transgender History book for Seal Press. I’d edited The Transgender Studies Reader, which won a Lambda Literary Award. I’d made the film Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria, which won an Emmy. And I had management experience in the non-profit sector. Over time, all of that added up to something that universities were interested in, even though I was doing anything very different in the mid-2000s than I’d been doing in the mid-1990s. I used to say back then that I would never get an academic job until the people I knew as undergrads and grad students became associate professors sitting on the hiring committees, and that’s exactly how it worked out. In 2007 a colleague I knew through the film festival circuit invited me to apply for a visiting professor position at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, and worked from the inside to make sure I got the job. I got it. And as soon as I had that title in my signature line—Professor—and an academic email address, I had different kind of visibility and legitimacy. It took me 15 years to go from Ph.D. to Professorship.

What advice would you give to someone early in their career?

Go just put your stuff out there and see what happens. Live your best life, try things out, call it the way you see it, follow your bliss, figure out how to keep food in your belly and a roof over your head. As you go along, try to get all of those things to align as best they can.

How do you manage it all? Any secret tips?

Well, I don’t know that I would recommend this as a general practice, but I’m increasingly open about using psychedelics. For me, part of being trans is having a sense of self that is unreal to others, even if it is deeply real for me. I am very attuned to the awareness of the dominant reality being a collective fiction, and to how material practices, both individual and group, can generate new realities. This is not too far from those old questions about religiously-motivated sociogenesis that drove my doctoral research. Psychedelic experience similarly gives me insight into how reality can be both actual and otherwise. I think substances can be chemical teachers. There’s a whole new psychedelic movement going on right now, using them to heal from PTSD and trauma, and to treat depression and addiction. For the last couple of years I’ve been doing ketamine-assisted meditation. It’s really interesting and I think it’s been really good for me. I don’t think of it as recreational–I actually have a prescription and work with a therapist. It seems paradoxical—most people think of psychedelics as being really “out there,” but for me they feel very grounding and help me integrate a lot of different dimensions of life, thought, feeling, and action.

There’s a whole new psychedelic movement going on right now with PTSD and trauma healing. I started using ketamine because I had a problem with something called frozen shoulder. I was doing acupuncture and massage and physical therapy.

I was at a Thanksgiving party and I met a psychotherapist who recommended ketamine-assisted therapy to me. She works with people who have really severe trauma and PTSD. She said that with any kind of chronic pain there is always an injury. It becomes chronic because of your emotional relationship with it.

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic. It gives you a very different sense of embodiment, and a different relationship to consciousness, place, and the body. Whatever might be happening chemically, physiologically, that is what’s happening emotionally. Ketamine gives you the space to feel in your body how something can be different. It’s a different way to hold yourself. Creating that awareness of the space for a potential difference becomes the space that you can move into.

What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Even when I recognize advice that comes from a well-intentioned place, I find that I actually know what’s best for myself. Advice is good for triangulating and situating, but really, you listen to yourself. Or maybe, listen to that quiet place in the center of your being where the cosmos manifests itself to you.

How do you listen to yourself?

I think it involves putting ego aside, actually, that it’s self-less to a significant degree. It’s about holding yourself open to experiencing the qualities and intensities of being that flows through you. The cosmos manifests in a particular way that is shaped through your consciousness, experience, history, and language, but it is not “you” in a personal sense. All the egotistical personal parts of you are adjacent to the creative wellspring, and they can report on what’s happening, but it’s not like your insights are something that you invented. It’s more of a witnessing of something that is essentially beyond you. For me, the creative process is very humbling, it’s a standing aside and a holding of space, where I try to use certain learned skill sets to communicate to others what emerges in that space. It’s like opening a portal, and listening to an echo coming out of the void that teems with virtual life that is constantly materializing into actuality, where your own situatedness in that process of becoming is part of how the cosmos unfolds.

What are the qualities you look for in a friend?

Loyalty, honesty, openness, and reciprocity. Sometimes I find that people bring a lot of needs to me, they want me to be something for them that might not be what I am for myself. I feel it’s very easy for my relationships to become unbalanced when people ask more me than I ask of them in friendship, relationship, even love relationships. So, reciprocity is really important for me.

What do you mean by loyalty?

People who stick with you through all the changes. We’re not the same person yesterday as we will be tomorrow. Loyalty is when someone is with you iteratively, as you are with them through their iterations. I think this is my historian’s sensibility as well as my transperson sensibility. I’m down for the long haul. I like ongoingness. I’ve been with my current partner for twenty-five years. I feel really committed to long-term relationships. I like to stay in touch with family, with people from childhood, high school, college, or grad school, from times of life gone by. You can always make new friends, but you can’t ever make new old friends.

Where do you go to find hope?

Thinking about the biggest possible picture. I think that our understanding of time and space is very particular to the ways the perceptual apparatus of our body is organized. Time and space are not in nature, they are in our perceptions of material existence. There’s a cultural component in how you learn to create conceptual packages for time and space.

My belief—or my faith, if you want to call it that—is that time and space are illusions and there is a persistence to being, a four-dimensional history of the whole cosmos from the Big Bang to heat death. Or maybe the cosmos breathes, collapsing into a singularity before expanding into something else and then regathering in a different way. However we think about the bigness of the cosmos, if we just accept that our species has always been and will always be present in it, that we have our own little four-dimensional squiggle in the fabric of space-time mattering, it’s all good. Everything dies, everything changes, everything moves on. And everything is part of the same life. So, it’s all good. Don’t worry. Don’t sweat the small stuff.

On a nearer term, I do think about death. Not in a morbid way. I’m coming up on sixty. My partner is a little older than me. I’ve got friends who are in their seventies and eighties. Death happens. There’s something specific to my stage of life, I think, in my increasing attention to death. But I actually find something very hopeful in thinking about death. One of the things that we need to be working on as a culture is not being in denial about what’s happening to the planet. Shit is breaking. It’s dying. Dying is just the dissolution of one pattern and the emergence of another pattern. In our culture we need to have a different ritual around death. Different funerary practices, a different cultural awareness of death, a different kind of ritual and symbolic encounter with the fact that we don’t live in a world of endless resource extraction. We’re going to hit a limit. Right? So, I find hope in the inevitability of death at many scales, which might sound like a very paradoxical thing, but it involves the on-going emergence of life in some new pattern. Just not one that you will personally be able to reflect on, even though what has been “you” will be a part of it. There is something quite beautiful in that process.

How would you like to be remembered?

It’s not something I think about a lot. I like to do the things that I like to do and then I’ll be dead and won’t care. The doing of it now is enough.

On a pettier level, I’ll tell you one thing, though, that annoys me. Having had a public career for about thirty years at this point, there are people who have been born after I came out and started doing work who are now grown up and fully functional adults. When younger people misremember, misunderstand, or mischaracterize something I’ve experienced directly, or something I myself have done, or something I’ve written, a little egotistical part of me feels like: “No, that’s not what it was like. That’s not what I said. That’s not what I did. You don’t understand where I was coming from.” I have to work to not feel annoyed at people’s completely understandable ignorance. They’re learning their world. They’re making sense of what the world looks like from their perspective, not mine. I need to listen to that. I don’t want to fall into authorial fallacy. It’s not like: “I said it, and this is why, and if you think differently, you’re wrong because I’m the person who wrote it.” It’s a good practice, to cultivate humility.

I get approached by people all the time who have taken elements of what I’m like and they’ve created someone in their head based on things they know about me, or based on what they want or what they feel hungry for, and they expect me to be something for them. They have some image of who they think I am that has absolutely nothing to do with my life. Increasingly, I have the sense that I am not recognized as a person because of my accumulated body of my work. I breathe life into a practice of interpreting the world, and it is what it is. The work is not me, even if it’s also not not me. It just came through me and of me.

Ideally, I guess I would like to be remembered more or less accurately when judged by the standpoint of my intention, and the context. I’m a very straight-forward, casual, curious, and somewhat opportunistic and experimental person. I haven’t had a plan, or an ulterior motive, or a rhyme or a reason to what I’ve done. I was just doing my thing, in whatever world opened up in front of me, to unfold the mystery of my transness to myself, and to help make more room for trans experience for others.

Thank you for your brilliant time.

I like to think that I’m just a transcriber of the brilliance of being as it manifests itself to me. But if you see brilliance when you listen to me, then I’m transcribing it well, so thank you.

To stay up to date with Susan Stryker, check out her 2021 Mills College Trans Studies Speaker Series.

The Past is as Fluid as the Future

In Conversation with Susan Stryker

This photo was taken for a Tucson Weekly story about the trans studies initiative at University of Arizona. The backdrop is the courtyard of the Gender & Women’s Studies building.

Susan Stryker, who received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, and completed her postdoctoral research at Stanford, is a pioneer in the field of transgender studies. Before her appointment at Mills, Professor Stryker held appointments at Harvard, Yale, University of California, Santa Cruz, and Simon Fraser University. Susan Stryker is Professor Emerita of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona, and Barbara Lee Distinguished Chair in Women’s Leadership at Mills College. According to Inside Higher Ed, she is “a driving force” in expanding academic programs and faculty hiring for transgender studies.

Also a longtime award-winning activist, author, and filmmaker, Professor Stryker is co-founder of direct-action activist group, Transgender Nation, and executive director of San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society, 1999-2003. She is co-founder of the TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, the first academic journal in the humanities and social sciences devoted to exploring transgender issues through an expressly interdisciplinary lens. Prior to this, Professor Stryker was among the first openly transgender authors to ever publish an academic article in a peer-reviewed journal.

Interviewed by Billy Lezra and Liam Lezra | October 12, 2020

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How are you?

In general? Same crises as everybody else. Not necessarily the same boat, but the same storm. There’s the COVID pandemic, the public health crisis, the economic crisis, the crisis of democracy in the U.S. The forests are burning here in California, the air has been unbreathable. The seas rise, the glaciers melt, the hurricanes rage and the deserts creep. You know, just the usual, right? But at an individual level, I live a relatively privileged life. I have a comfortable place to live, a salary for the time being, I eat well, I get enough sleep, I exercise regularly, I stay hydrated. I’m fine. The people closest to me are fine. As long as the whole social system doesn’t collapse, I’m as good as anybody could reasonably expect to be.

How did you decide to become a professor?

I come from a working class, rural, southern white background. I didn’t come from a family that had a lot of access to higher education, but I was groomed in this upwardly mobile way that encouraged me to go to college. For the longest time, I really thought I would go into medicine. That would be a good job that I could get if I had a good education. Besides, I was fascinated with bodies.

But what I realized as soon as I got to college was that I hated my science classes. They seemed dull to me, too mechanistic, like they already had all the answers to all the questions. I realized—this is how I formulated my dissatisfaction in my eighteen year old brain—that I was not interested in how bodies functioned, but rather in what bodies meant. That was a humanities question, not a science question. It had never dawned on me that you could go to college to study the humanities. I switched degrees from Zoology/Pre-Med to Letters after my first semester as a freshman, and never looked back.

The Letters major at the University of Oklahoma where I went to college on scholarship was really cool. You had to have upper-division concentrations in Philosophy, History and Literature, plus three years’ study of a one modern and one classical language, fines arts appreciation and history of science, and a minor; I minored in Economics. I was also in the honors program, which meant that instead of big mass lectures, I got to take small seminars with professors for all of my core classes. It was like I discovered a secret small little liberal arts college hidden inside the machinery of Big State U.

After I shifted gears, I had no idea what I was going to do for a career. I never wanted to be an elected official, but I thought I’d be really a good policy wonk on a campaign, or a strategist. I was active in student government. Then between my sophomore and junior years I interned with the Oklahoma State Senate Legislative Research Office and decided that there was no fucking way was I going to go into politics.

My junior year, it was like, Ding, Ding, Ding! I really enjoy being in college—I should become a professor! That still promised the class mobility I associated with being a medical doctor, but with the bonus of stay in college for the rest of my life and getting to think about the things I think are interesting.

What are you interested in thinking about?

I’m interested in interpretive questions. Part of what makes history interesting to me is that it sits on that boundary between empirical evidence—the material trace that an event has left in some record—and the creativity of storytelling. There’s a common but misguided assumption that the past is fixed in place and we just have to recover knowledge about it somehow. That a fact that happened, we will learn about it, and then we will know what the past means.

But I find the past to be in many ways as fluid as the future. There is always a speculative dimension to recovering the past. That doesn’t mean you can just make stuff up, history is at some level a practice of truth-making, but the truth of the past isn’t fixed or predetermined. The past is a foreign country in some ways, where you find things that you weren’t expecting based on their difference from present-day understanding. I think that’s actually the politically radical promise of studying history: that it empirically documents the actual existence of a social order different from now. And just as the past is different from now, transpositionally, the future can be different from now. Ultimately, history bears witness to the inescapability of difference and the inevitability of change. That’s hopeful for all of us who feel oppressed by the current organization of the world.

How did you decide to pursue a Doctoral Degree at UC Berkeley in United States History?

Based on my undergrad Letters major, I thought I should pursue my “good job” in either History, Philosophy, or Literature. At the time, I considered literature to be limited to questions of representation, and philosophy to questions about ideas and concepts. I thought of History, on the other hand, as the study of all human culture in the contexts of time and place. Why not swing for the fences? But then to narrow that vastness down, I had to answer the question of “history of what?” And I decided on U.S. history, since that’s where I’m from. Like my earlier interest in bodies that I was pursuing through medicine, my interest in history was largely rooted in questions about myself as a trans person. In hindsight, I can see that I was first asking questions about “how can my body be like this, and my identity be like that?” and later asking questions about how identities always emerge in specific historical circumstances that provide their “conditions of possibility.” But all along my “research” was based on “me-search” at some level. How was it possible that a person like me existed?

When I graduated from college in 1983, there were actually really poor prospects for getting a professorship, given that all the Baby Boomers already had tenure in those sorts of jobs and were still a long way from retiring. So I decided to apply to only the most highly rated History programs, figuring if I could get in I’d stand a good chance of landing one of a small number of available jobs. If it didn’t work out, I was planning on being a bartender and working on a novel.

I applied to Berkeley, Harvard, Yale, Michigan and North Carolina, which at the time were rated the top five history programs by the American Historical Association. I got into Berkeley, Michigan and North Carolina. Berkeley was actually my number one choice. Growing up mostly in Oklahoma but having lived in Europe and the Pacific because my father was in the Army, I knew there was a wider world I wanted to move in. When I was a kid, I always said I wanted to live someplace that other people go to on vacation. And when I saw San Francisco on television and thought, “That’s a really beautiful, interesting city by an ocean. That could be a good place to live.” Then Harvey Milk was assassinated my junior year of high school. I thought that if a gay person could be elected to citywide office in San Francisco, that must mean that there are a lot of gay people in San Francisco, and that it might be a good place to be trans. And then, to top it off, I learned that Berkeley was right across the Bay from San Francisco. I was very inspired in the student movements of the sixties, and knew Berkeley was where the revolution was happening. The thought of being in that milieu was really exciting. Getting into Berkeley felt like winning the lottery. It was a beautiful place to go and become radically queer.

What did you write your dissertation on?

The origins of Mormonism. Think about it: in 1825, there is no such thing as a Mormon. They don’t exist. The name has not been invented. No Mormon walks the face of the earth. It’s just not a thing yet. Twenty years later, in 1845, there’s a new church, there’s a new body of sacred literature, there’s a new cosmology, there are new forms of kinship, there’s transcontinental migration; there’s an anti-Mormon backlash. A new identity and community formation simply erupted onto the stage of history in very short order. I wrote about Mormonism as a case study in the formation of marginal cultural identities. It was kind of a crypto-trans project, written at a time when it was not possible to study trans history more directly. I never published that work, but what I learned about the process of sociogenesis during my Ph.D. studies informs everything I’ve done since.

What did you do when you finished your doctoral program?

I’d been aware of my trans feelings since early childhood, but it wasn’t until I was in my later 20s that my dysphoria was so strong that I simply had to transition, no matter the consequences. It was hard. I was married, and that blew up. It was virtually impossible to be taken seriously for professorial jobs as an out trans person. It was virtually impossible to be taken seriously for any job at all—employment discrimination against trans women is a very, very real thing. I was dirt-poor, trying to pay off student debt. I was living in a collective household in Oakland with a motley crew of anarchist, queer folks who were ten years younger than me. I had to hustle, making money however I could. I’ve called the period after I finished my Ph.D. my seven year unpaid residency in transgender studies.

I’ve often said that there’s only one job most trans women are allowed to have, and that’s to figure out how to get other people to pay you for being a trans woman. I decided to do that by using my historical training to learn and teach about trans history. That’s going to be my shtick, the thing I knew how to do, that felt live “right livelihood,” whether or not it actually paid the rent. The 90s were a hard decade for me. There was a real sense of financial deprivation. I made less money than I was making as a graduate assistant. I hovered around ten thousand dollars a year for seven years, living in the Bay Area which is not cheap. I would not have made it without my community.

I felt like I won the lottery again in 1998 when I was awarded a Ford Foundation/Social Science Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship that let me study history of sexuality at Stanford for a couple of years. It was like forty thousand dollars a year, which was four times what I had been living on. But it was also a huge validation for the grass-roots work I’d been doing on trans history, a big stamp of approval and recognition from the powers that be. Plus I now had enough money to complete my medical transition. My life changed a lot in 1998.

How did you become the Executive Director of the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco?

I had been involved with the Historical Society since ’91, when I was just coming out as trans and finishing my Ph.D. I started as a volunteer. Then I was asked to join the board of directors, and I became very involved with the organization. It was a real base of operations for me as I delved into trans history. By 1998, when I got the post-doc at Stanford, the organization was kind of falling apart during in the first wave of the dot-com boom. Our rent was about to triple. Nobody in the organization had any real experience with fundraising or organizational development. Things could have simply collapsed. But since I had some new-found income through my post-doc, I said: “Let me become the organization’s executive director”—we’d been an all-volunteer group with no paid staff—“and I’ll do it for a stipend”—I think I said $5000—“but if I can raise the money we need to keep the doors open and pay real staff salaries, then when my post-doc runs out I want to be hired half-time with healthcare benefits.” I thought it would be a great day job, that would let me continue with my research. So that’s what the organization did, I think mostly in desperation. And that’s when I found out that I could raise significant amounts of money. During my “unpaid residency” I had learned how to hustle and sniff out opportunities that nobody handed to me.

What was your path to becoming a professor?

By the mid 2000s I’d written some academic articles that were retroactively positioned as foundational to the emerging field of transgender studies. I had written a couple of coffee-table books on queer history, as well as the first edition of my Transgender History book for Seal Press. I’d edited The Transgender Studies Reader, which won a Lambda Literary Award. I’d made the film Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria, which won an Emmy. And I had management experience in the non-profit sector. Over time, all of that added up to something that universities were interested in, even though I was doing anything very different in the mid-2000s than I’d been doing in the mid-1990s. I used to say back then that I would never get an academic job until the people I knew as undergrads and grad students became associate professors sitting on the hiring committees, and that’s exactly how it worked out. In 2007 a colleague I knew through the film festival circuit invited me to apply for a visiting professor position at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, and worked from the inside to make sure I got the job. I got it. And as soon as I had that title in my signature line—Professor—and an academic email address, I had different kind of visibility and legitimacy. It took me 15 years to go from Ph.D. to Professorship.

What advice would you give to someone early in their career?

Go just put your stuff out there and see what happens. Live your best life, try things out, call it the way you see it, follow your bliss, figure out how to keep food in your belly and a roof over your head. As you go along, try to get all of those things to align as best they can.

How do you manage it all? Any secret tips?

Well, I don’t know that I would recommend this as a general practice, but I’m increasingly open about using psychedelics. For me, part of being trans is having a sense of self that is unreal to others, even if it is deeply real for me. I am very attuned to the awareness of the dominant reality being a collective fiction, and to how material practices, both individual and group, can generate new realities. This is not too far from those old questions about religiously-motivated sociogenesis that drove my doctoral research. Psychedelic experience similarly gives me insight into how reality can be both actual and otherwise. I think substances can be chemical teachers. There’s a whole new psychedelic movement going on right now, using them to heal from PTSD and trauma, and to treat depression and addiction. For the last couple of years I’ve been doing ketamine-assisted meditation. It’s really interesting and I think it’s been really good for me. I don’t think of it as recreational–I actually have a prescription and work with a therapist. It seems paradoxical—most people think of psychedelics as being really “out there,” but for me they feel very grounding and help me integrate a lot of different dimensions of life, thought, feeling, and action.

There’s a whole new psychedelic movement going on right now with PTSD and trauma healing. I started using ketamine because I had a problem with something called frozen shoulder. I was doing acupuncture and massage and physical therapy.

I was at a Thanksgiving party and I met a psychotherapist who recommended ketamine-assisted therapy to me. She works with people who have really severe trauma and PTSD. She said that with any kind of chronic pain there is always an injury. It becomes chronic because of your emotional relationship with it.

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic. It gives you a very different sense of embodiment, and a different relationship to consciousness, place, and the body. Whatever might be happening chemically, physiologically, that is what’s happening emotionally. Ketamine gives you the space to feel in your body how something can be different. It’s a different way to hold yourself. Creating that awareness of the space for a potential difference becomes the space that you can move into.

What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

Even when I recognize advice that comes from a well-intentioned place, I find that I actually know what’s best for myself. Advice is good for triangulating and situating, but really, you listen to yourself. Or maybe, listen to that quiet place in the center of your being where the cosmos manifests itself to you.

How do you listen to yourself?

I think it involves putting ego aside, actually, that it’s self-less to a significant degree. It’s about holding yourself open to experiencing the qualities and intensities of being that flows through you. The cosmos manifests in a particular way that is shaped through your consciousness, experience, history, and language, but it is not “you” in a personal sense. All the egotistical personal parts of you are adjacent to the creative wellspring, and they can report on what’s happening, but it’s not like your insights are something that you invented. It’s more of a witnessing of something that is essentially beyond you. For me, the creative process is very humbling, it’s a standing aside and a holding of space, where I try to use certain learned skill sets to communicate to others what emerges in that space. It’s like opening a portal, and listening to an echo coming out of the void that teems with virtual life that is constantly materializing into actuality, where your own situatedness in that process of becoming is part of how the cosmos unfolds.

What are the qualities you look for in a friend?

Loyalty, honesty, openness, and reciprocity. Sometimes I find that people bring a lot of needs to me, they want me to be something for them that might not be what I am for myself. I feel it’s very easy for my relationships to become unbalanced when people ask more me than I ask of them in friendship, relationship, even love relationships. So, reciprocity is really important for me.

What do you mean by loyalty?

People who stick with you through all the changes. We’re not the same person yesterday as we will be tomorrow. Loyalty is when someone is with you iteratively, as you are with them through their iterations. I think this is my historian’s sensibility as well as my transperson sensibility. I’m down for the long haul. I like ongoingness. I’ve been with my current partner for twenty-five years. I feel really committed to long-term relationships. I like to stay in touch with family, with people from childhood, high school, college, or grad school, from times of life gone by. You can always make new friends, but you can’t ever make new old friends.

Where do you go to find hope?

Thinking about the biggest possible picture. I think that our understanding of time and space is very particular to the ways the perceptual apparatus of our body is organized. Time and space are not in nature, they are in our perceptions of material existence. There’s a cultural component in how you learn to create conceptual packages for time and space.

My belief—or my faith, if you want to call it that—is that time and space are illusions and there is a persistence to being, a four-dimensional history of the whole cosmos from the Big Bang to heat death. Or maybe the cosmos breathes, collapsing into a singularity before expanding into something else and then regathering in a different way. However we think about the bigness of the cosmos, if we just accept that our species has always been and will always be present in it, that we have our own little four-dimensional squiggle in the fabric of space-time mattering, it’s all good. Everything dies, everything changes, everything moves on. And everything is part of the same life. So, it’s all good. Don’t worry. Don’t sweat the small stuff.

On a nearer term, I do think about death. Not in a morbid way. I’m coming up on sixty. My partner is a little older than me. I’ve got friends who are in their seventies and eighties. Death happens. There’s something specific to my stage of life, I think, in my increasing attention to death. But I actually find something very hopeful in thinking about death. One of the things that we need to be working on as a culture is not being in denial about what’s happening to the planet. Shit is breaking. It’s dying. Dying is just the dissolution of one pattern and the emergence of another pattern. In our culture we need to have a different ritual around death. Different funerary practices, a different cultural awareness of death, a different kind of ritual and symbolic encounter with the fact that we don’t live in a world of endless resource extraction. We’re going to hit a limit. Right? So, I find hope in the inevitability of death at many scales, which might sound like a very paradoxical thing, but it involves the on-going emergence of life in some new pattern. Just not one that you will personally be able to reflect on, even though what has been “you” will be a part of it. There is something quite beautiful in that process.

How would you like to be remembered?

It’s not something I think about a lot. I like to do the things that I like to do and then I’ll be dead and won’t care. The doing of it now is enough.

On a pettier level, I’ll tell you one thing, though, that annoys me. Having had a public career for about thirty years at this point, there are people who have been born after I came out and started doing work who are now grown up and fully functional adults. When younger people misremember, misunderstand, or mischaracterize something I’ve experienced directly, or something I myself have done, or something I’ve written, a little egotistical part of me feels like: “No, that’s not what it was like. That’s not what I said. That’s not what I did. You don’t understand where I was coming from.” I have to work to not feel annoyed at people’s completely understandable ignorance. They’re learning their world. They’re making sense of what the world looks like from their perspective, not mine. I need to listen to that. I don’t want to fall into authorial fallacy. It’s not like: “I said it, and this is why, and if you think differently, you’re wrong because I’m the person who wrote it.” It’s a good practice, to cultivate humility.

I get approached by people all the time who have taken elements of what I’m like and they’ve created someone in their head based on things they know about me, or based on what they want or what they feel hungry for, and they expect me to be something for them. They have some image of who they think I am that has absolutely nothing to do with my life. Increasingly, I have the sense that I am not recognized as a person because of my accumulated body of my work. I breathe life into a practice of interpreting the world, and it is what it is. The work is not me, even if it’s also not not me. It just came through me and of me.

Ideally, I guess I would like to be remembered more or less accurately when judged by the standpoint of my intention, and the context. I’m a very straightforward, casual, curious, and somewhat opportunistic and experimental person. I haven’t had a plan, or an ulterior motive, or a rhyme, or a reason to what I’ve done. I was just doing my thing, in whatever world opened up in front of me, to unfold the mystery of my transness to myself, and to help make more room for trans experience for others.

Thank you for your brilliant time.

I like to think that I’m just a transcriber of the brilliance of being as it manifests itself to me. But if you see brilliance when you listen to me, then I’m transcribing it well, so thank you.