A Thoughtful Exchange

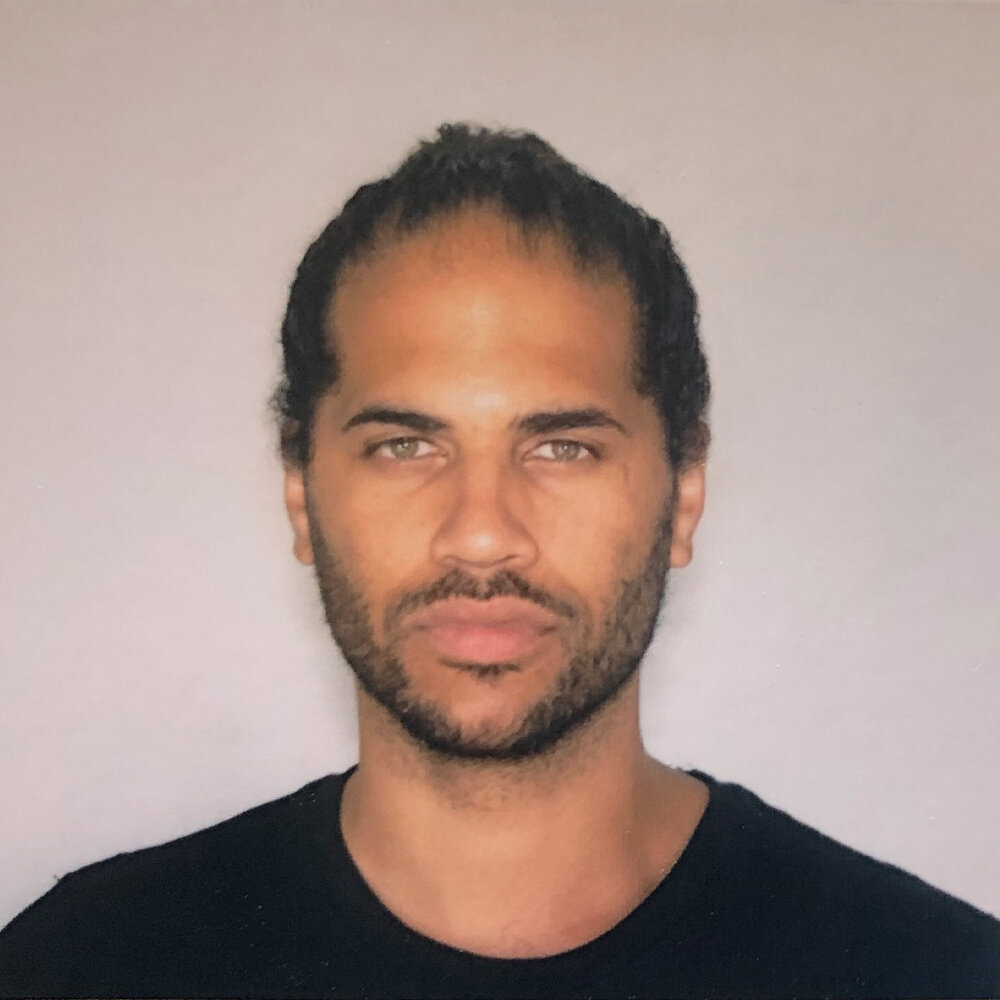

In Conversation with Brett Childs

a concerted effort and pressure

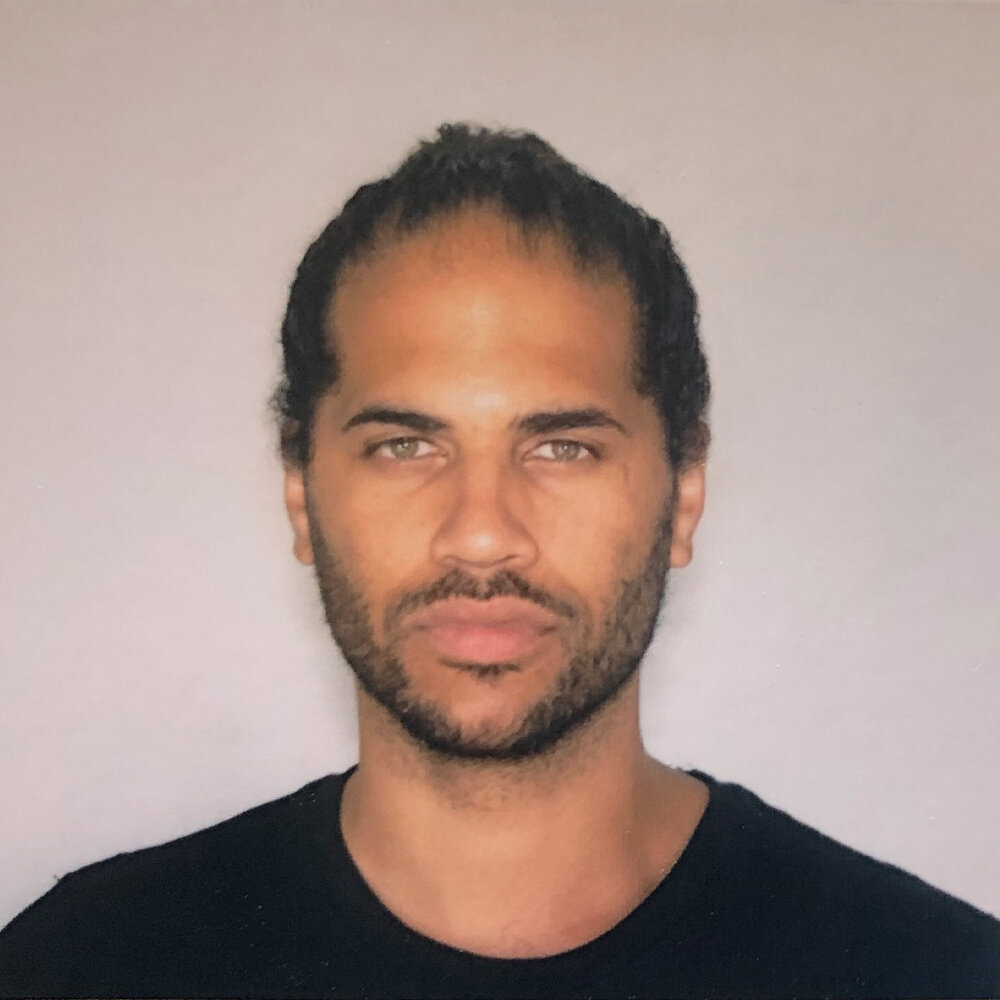

Brett Childs is a photographer and thinker, focused on the relationship between individuals and the larger groups that they constitute. Specifically, he is interested in what agency individuals possess in a world largely comprised of complex systems. The images he makes are always, in one way or another, about the individual. He strives to allow his subjects to be recognized, rather than just seen.

Interviewed by Liam Lezra | June 30, 2020

When did you first realize that you could explore and express abstract concepts through photography?

The curtain was pulled back when I took that first class and learned what an f-stop was. It was a light switch. I saw how it all worked and this giant shroud of mystery was removed. I started shooting. It became clear that I had a developed eye. I was making a good image, made like I had seen before. It was aesthetically pleasing, well-lit; it was what was expected.

I started asking, how do I make something that people can really feel when they look at it? I still don’t have a concrete answer for that. I found what became really important is how I choose my sitters. Or, if they are choosing me, how am I responding? How am I trying to create an image with them?

In a studio, I want to have a thoughtful exchange. Once that happens, there is a vulnerability. What I want is to form a connection and try to capture that connection; other people may not know what our conversation was about, but they can look at the image and feel an emotional experience.

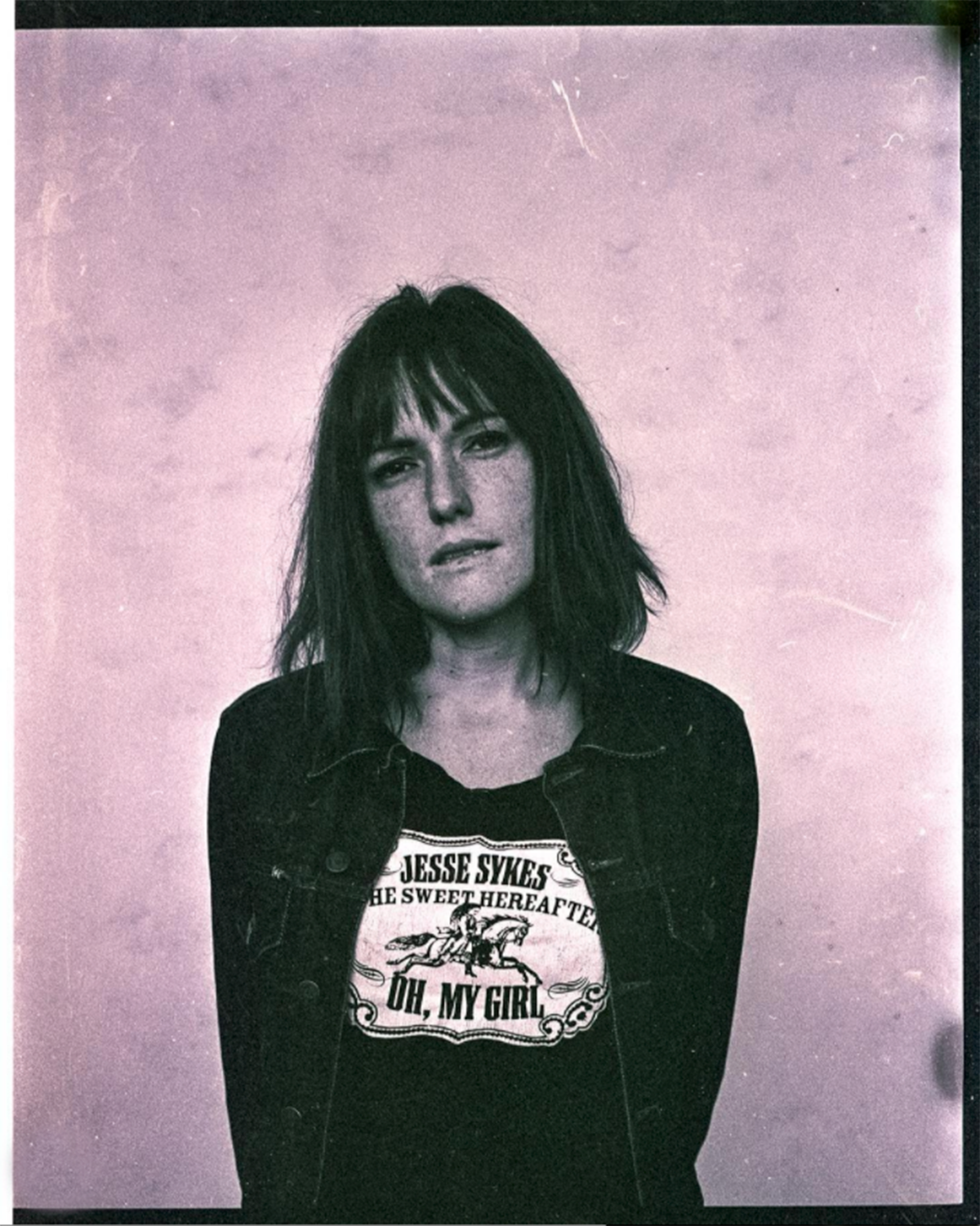

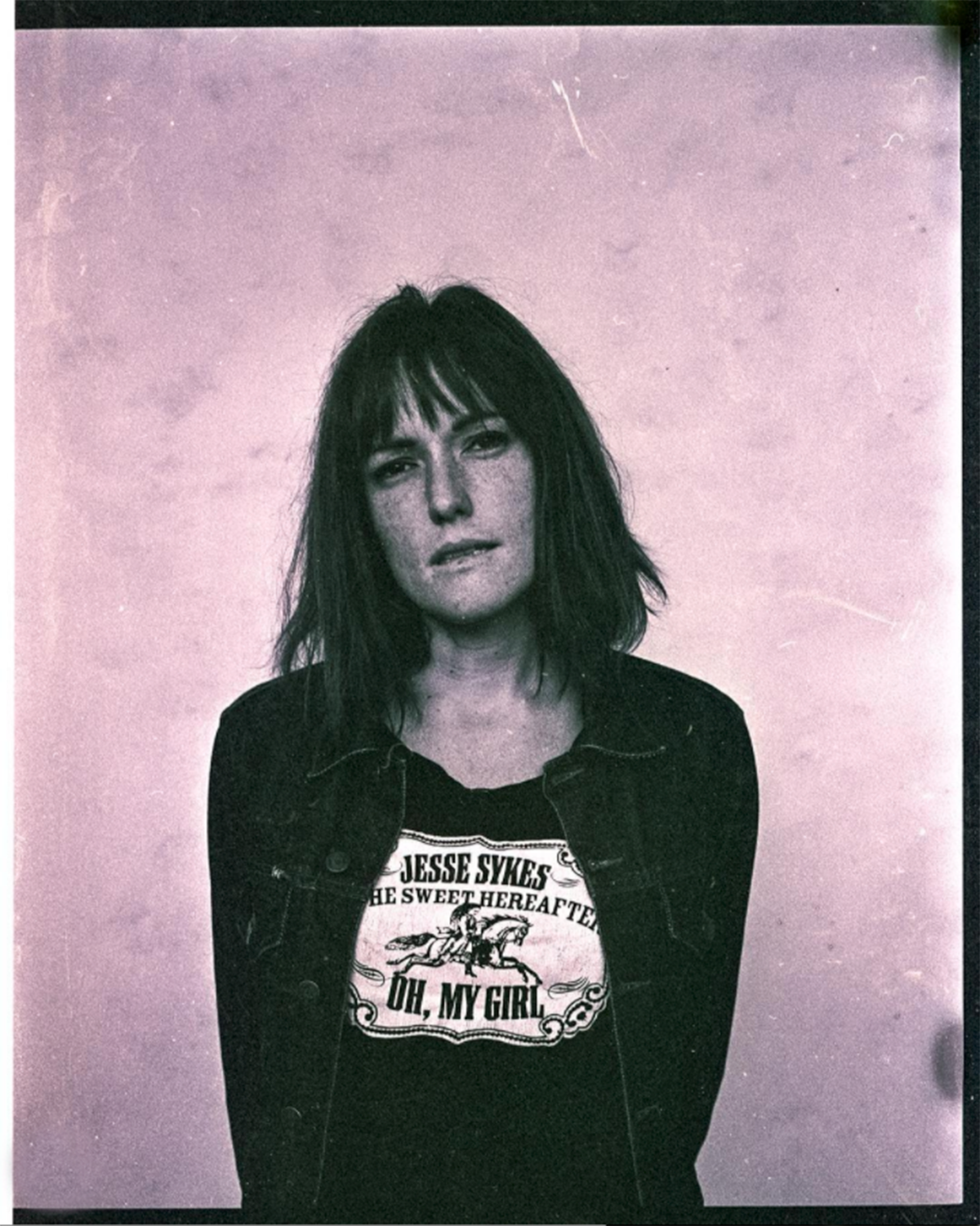

claire 2016

What kind of emotional experience do you want your viewer to have?

If I make an image that no one looks at, it’s never really finished.

I don’t want to color the internal conversation of the viewer, but I want to direct them. I try to make work that has a lot of entry-points. Once they are looking, they are doing a lot of work with what I put in front of them.

Often, the person I have in mind as the viewer is the person I am photographing. Everyone has a camera now. Everyone is having their picture taken. People are much more aware of what they think they look like. But really it’s because they see a camera and they have that same face they put on, and they see the pictures and say, “I don’t photograph well.” Okay, maybe. Maybe no one’s taken a good photograph of you.

It’s never that someone doesn’t photograph well. It’s that they don’t have any photographs of themselves that they like. I love when I’ve taken a picture and I show it to someone and they say, “Damn, I knew you were taking a picture, but when did this happen? Why didn’t I know it was going to be like this?”

I’m like, “Good. I hope you remember how this feels.”

How do you choose your subjects?

Usually, it’s people I’ve met. I’m interested in them as an individual. That’s how it starts. There’s some inkling or exchange I’ve had with them. Specifically for Against Monolith, the pool is limited to people of color, but it’s also people who have a very defined sense of individuality. Individuality is a big part of all of my images because we categorize things without even thinking about it. I’m interested in people who break out of categorization. It can be for a lot of reasons. I noticed that oftentimes it’s that someone has a very specific style.

The piece that is featured in Rough Cut, Julia, is a portrait of my sister. At that time, she had just started her Master’s Program in Social Work, specifically Critical Race Theory. She was hugely influential in this project because I love to read, so when she started her program the first thing I did was ask her to send me everything she was reading. Send your syllabi, all of your essays, everything.

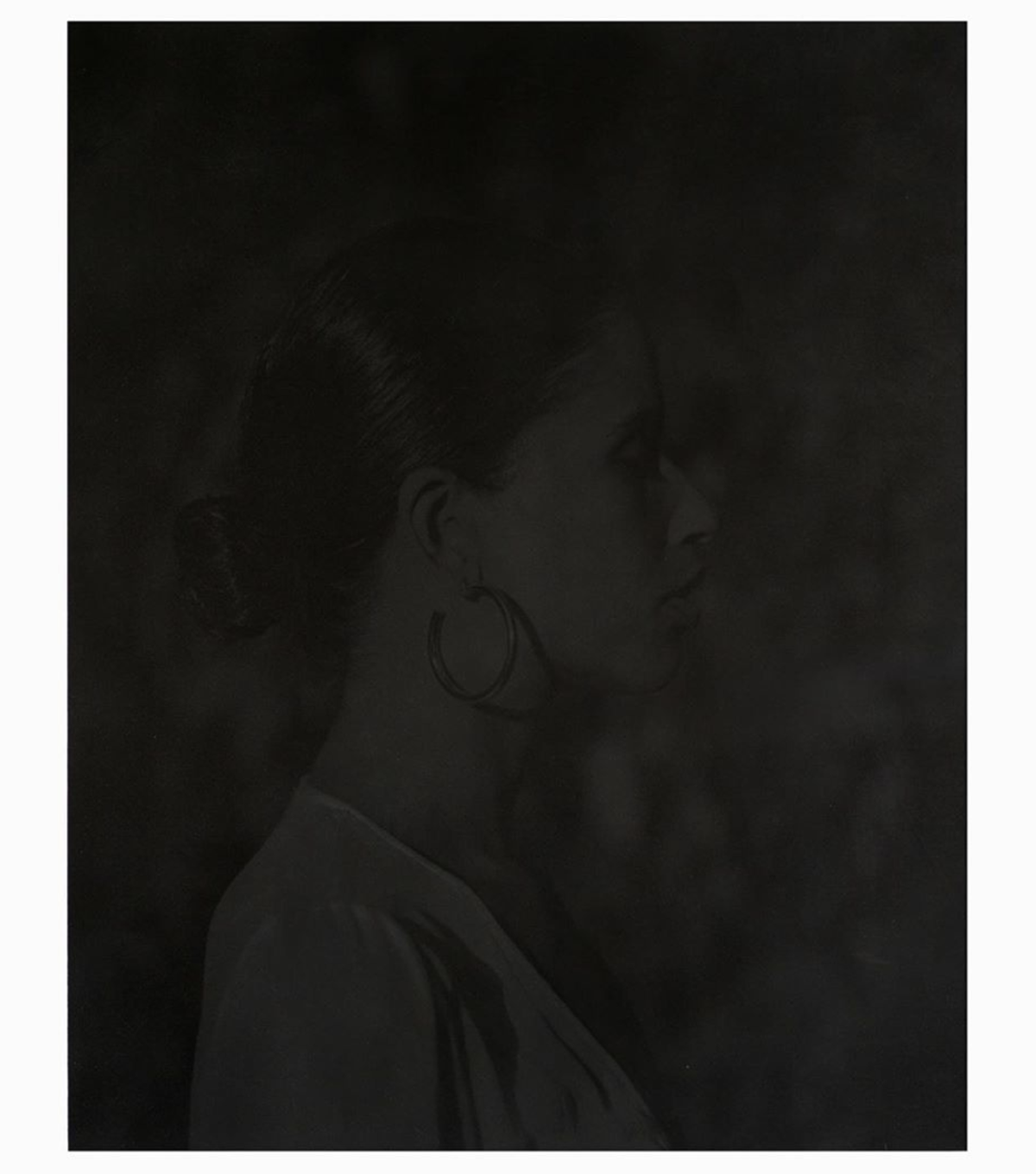

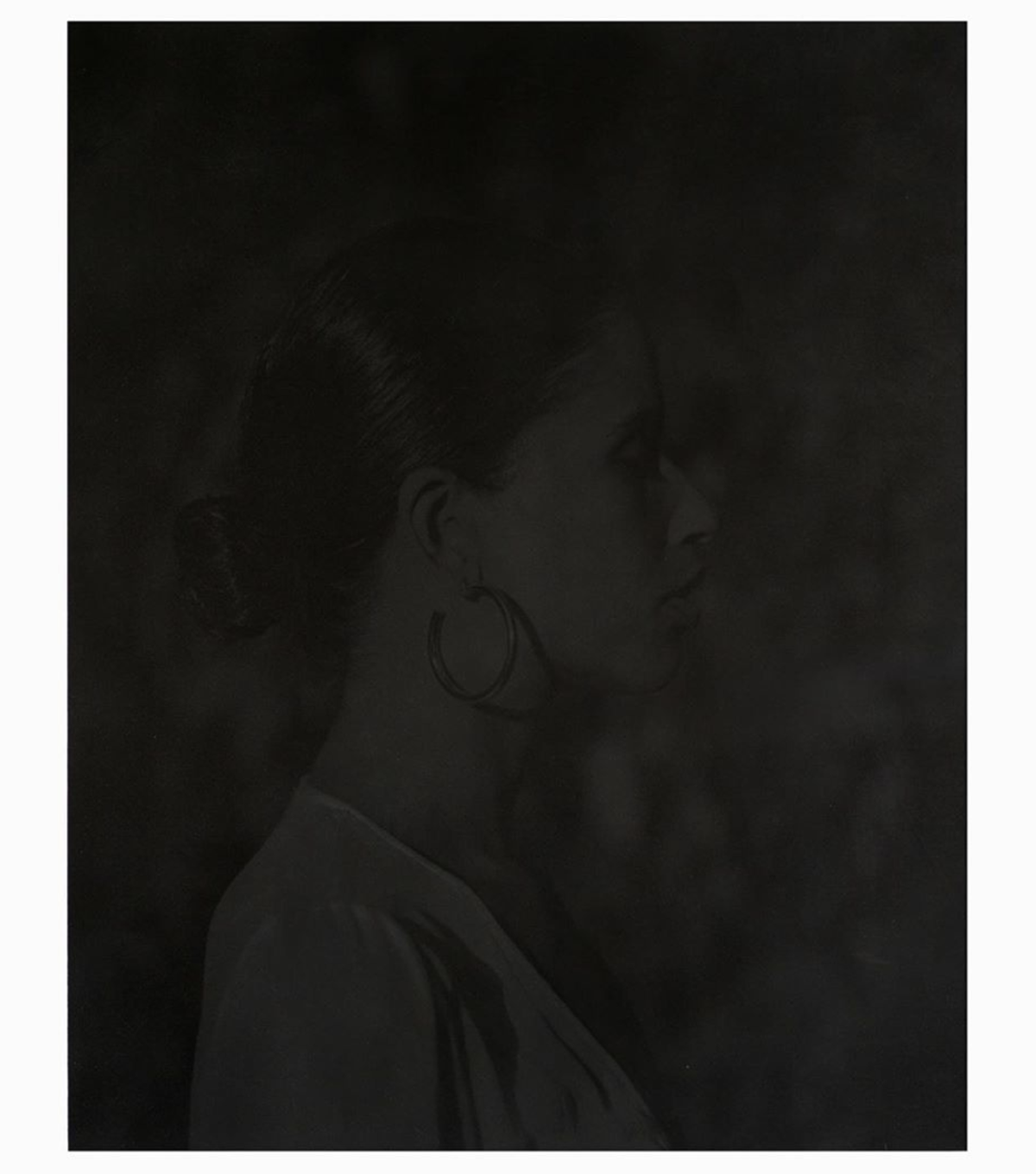

Julia – from Against Monolith

She is such an incredibly smart and caring person. Social work is a rough job. She just decided she wanted to be the person giving back, and she’s doing it in a big way. She’s specifically focused on generational trauma. My conversations with her became the rock and foundation for Against Monolith. It helps that she had a very solid background, both in her own experience and in doing the work to try and understand it better. I was able to try and understand my own experience and integrate that.

What inspired you to create this series, Against Monolith?

The project looks at this big thing that is happening, and it looks at little ways that it is also happening. The big thing is, “Are we recognizing people of color?” That question is happening all the time; on a structural level, on a personal level, it’s always happening.

I am a photographer, so I am looking at the history of the medium and how it can support the thoughts I am having. I was interested in earlier photographic work that involved individuation and identity formation. So, I started obsessively trying to tear apart and understand what forms an individual, which is always related to another individual or a group. I wondered: how do you maintain individuality when you’re in a group?

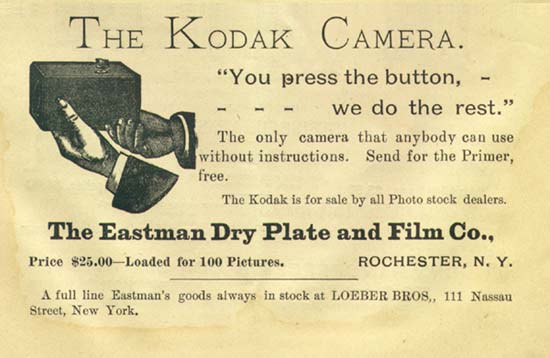

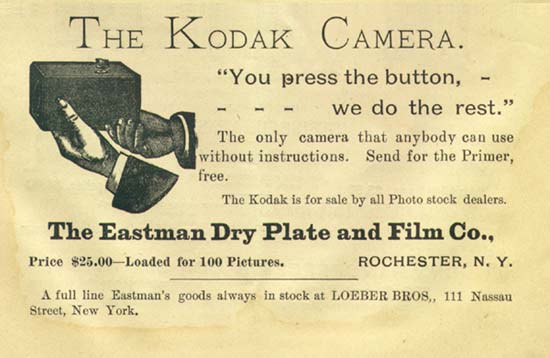

Then I wondered, how do you affect change? What is the efficacy of change? What can you change, as an individual? I started looking deeper into the history of photography. There’s been some writing about the history of Kodak Films. Goddard was a filmmaker who proclaimed Kodak films racist in the 70s. He wouldn’t use them to shoot a project because they couldn’t reliably capture the skin tones of people of color.

I was also taking a deep dive into what’s called the Zone System, which was developed by Ansel Adams for photography. It’s kind of a pre-visualization system. When you’re looking at a scene you want to photograph it helps you map all the tones in that scene mentally so you can execute it technically. If you’re looking at the zone system on a chart of grays, Zone 10 is pure white. Zone 0 is pure black. Skin tone is Zone 5. Zone 3 is shadow with detail and Zone 8 is highlight with detail. Zone 6, as skin tone, is an inherently Caucasian skin tone.

The test print at Kodak was called a “Shirley Card,” It changed over the years. Had some color bars, a bowl of fruit, a red dress. It was always a white woman, though. You could try and print your own negative that was taken of a person of color until it looks right to your eye, but there wasn’t a way of calibrating it, so your skin tones would be all off.

Kodak knew it was a problem, it was brought up for decades, they didn’t change anything. Eventually, it was chocolate manufacturers and furniture makers who said, “We’re not getting the correct tones in our advertising. This needs to be changed.”

Kodak & Rochester was a behemoth of research and development, but it wasn’t until the late seventies or eighties that it became a priority. Then they pushed an advertising campaign for film that would be more accurate with darker skin tones, or just darker things. They said you could photograph a black horse at night.

The first multi-racial Shirley Cards came out in the nineties.

To me, this is a really interesting example of how complex racism can be. It doesn’t matter if Kodak was acting in a racist way, because the lived experience of people was the same. If you were a person of color who was trying to get your wedding photo taken, that was the grinder with Kodak. You have dark skin and a white dress. If you’re a photographer trying to capture the detail in the dress, all of her skin tone is gone. She just turns into kind of a black smear. No bride wants to spend all the money on a dress for her special day and see no detail in the pictures.

Was there someone at Kodak Films thinking, “Hey, let’s continue to marginalize a whole group of people?” No, of course not. They were probably thinking, “No one is taking pictures of shadows.” People are always taking pictures of stuff that’s lit.

It doesn’t really matter, though, because the end result is the same, which is, great, I can’t get my fucking picture taken.

How did studying history of Kodak and the zone system affect your work?

I didn’t just want to illustrate the thing that’s happened. I didn’t want to take photographs where people turned into a black smear. That’s not very interesting. So I thought a lot about what we expect of portraits. How can I subvert that? Is there any sort of template for how to go about that? We’re used to seeing and recognizing people in portraits. How can I subvert that familiarity? How can I stop it?

What if I make an image where it’s hard to see anything? But make it in a way where you really want to see it? Let’s make an image that rejects images. A black square. I thought of Kerry James Marshall, who is a painter, and he has a lot of paintings that are similar to this idea. The one that sticks in my mind is a nude male in a room at night and it’s just layers of black that he’s painted, so it’s really hard to see. I thought, what would that look like as a photograph? That meets what I was looking for, how do I make that happen? And then the whole technical thing is really very boring and extremely involved.

When I showed my advisor my first print he was like, “This is it.”

When did you start the project?

I started at the end of 2018. I was midway through one of my later undergrad terms. I pulled my first test-print in October, but the thought behind it wasn’t as fleshed out as I wanted it to be. I took nine months off from shooting to consider all of the different ways I can look at subject formation and how it ties into race. I started trying to survey a whole field looking at race. Eventually, I decided that with this project, and with all of my projects, I don’t really want answers. I want to ask better questions because if I give you what I think is the answer, it becomes a very simple exchange of right or wrong; I believe it or I don’t. I want to ask better questions so anyone who’s viewing the work can try and form their own answers. I’m not really looking to have an answer, I’m looking to create an experience.

Eventually, I got to the point where I’d thought enough about it and started shooting again. Instead of trying to offer an answer, “This is what it looks like. This is what it is.” There wasn’t that thing. Which is often true in life. We’re used to a narrative structure of things. It’s how we often tell and retell stories. But there’s not necessarily a definitive end. Maybe for an individual, you might die, and that’s kind of a definitive end, but your story continues on and there is no end.

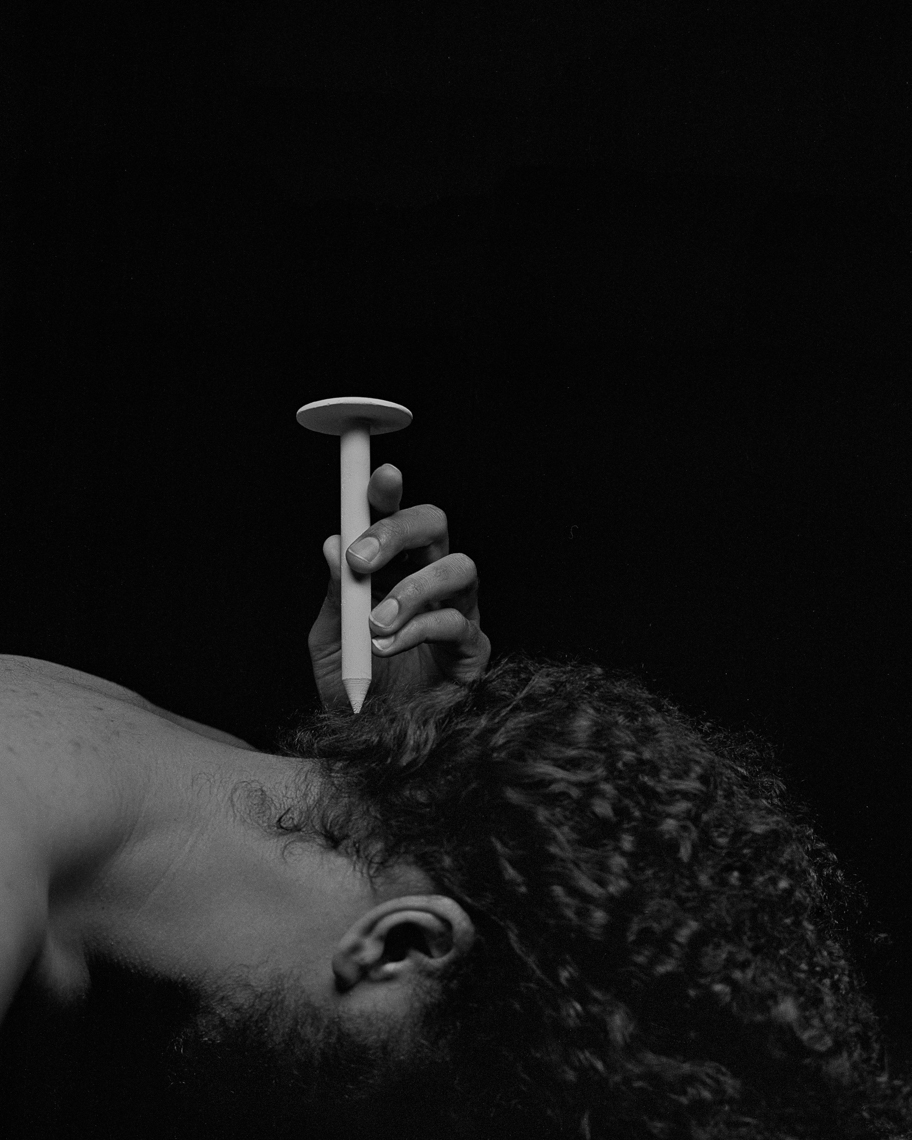

artificial

You don’t put a lot of work online.

It’s not how I want the images to be experienced. Ideally, I want them to be experienced in print. I’m very much into printed objects. I worked at a bookstore for twelve years, so it’s floating around in the DNA at this point. I would love for my work to be experienced in shows where you can come and talk to people, and have that sense of community and in-person conversation. Specifically with Against Monolith, it’s hard to show at all digitally. I have Julia hanging in our living room, and Claire and I talk all the time about how the light hits it. It activates it in space. At night you can hardly see it, but in the afternoon when the sunset is coming through the blinds it glows in a different way.

What struck me about Against Monolith was the element of time; I have to approach it and it takes time for my eyes to adjust and understand what I’m looking at.

Time is always an element of photography because you are capturing a piece of time. There are ways you can show time is happening, like motion blur or freezing motion, but it doesn’t really introduce that durational element.

Especially in an age when our relationship to imagery is fractions of seconds, when you put something in front of someone that they haven’t seen, it stops them. I have never shown someone this work and not had it stop them. You become aware of your senses as you try to realize what it is you’re experiencing. It takes time.

Where do you go to find inspiration?

Conversations with people. A lot of films, books, music. Film is very inspirational to me. I sometimes have the same experiential feelings watching film that I would if I was looking at an installation, or a sculpture.

Where do you go to find hope?

I find hope in conversations with people. It’s not a specific hope, because the more specifically I try to think about hope, it’s out the window. We’re hopeless. Sometimes it can be hard to find the moment to really listen and really be present to someone.

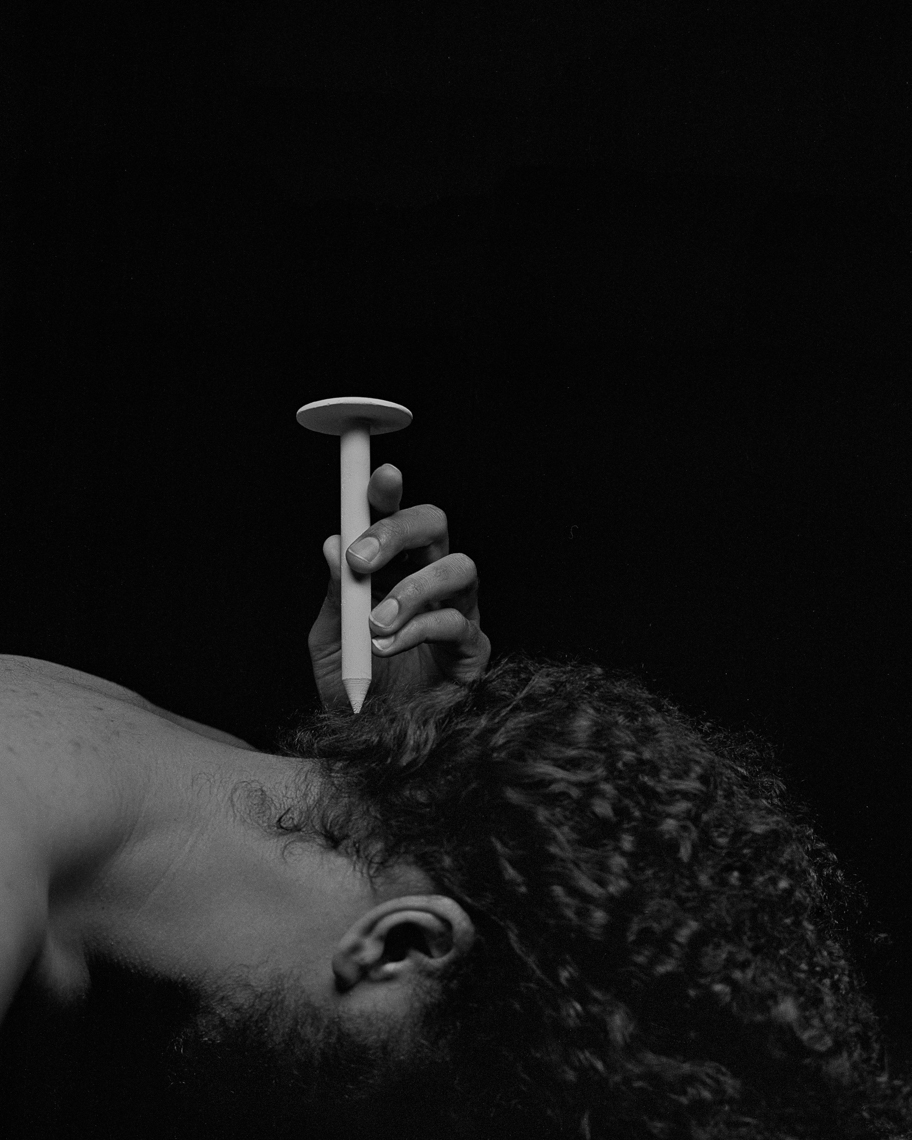

patrick

So, there’s hope in that deep listening and presence?

Yes, because I’m reminded that we’re not just groups, we are individuals. Once you start breaking into groups, on how many levels do you want to talk about disappointment? But that feeling changed with a lot of the protests that have happened lately. That was very hopeful. I didn’t think people would do it. Maybe it’s because we were sitting around and we weren’t at work, so we had the time to get up and say, “Fuck this.” I don’t know. But I was happy to see it. It was reassuring to see other people who care deeply, as well.

This is the most I’ve thought about hope in a long time. I need to sit and think about hope more than I do. It’s not really on my radar, maybe that needs to change.

How would you like to be remembered?

I don’t know if I have an attachment to being remembered. What do I want people to remember of me? Good conversation, maybe. I hope I made them think. Hopefully they’ll have good memories of well-intentioned conversations. I try to create good memories with people. I don’t want people thinking, “Fuck that guy.”

I mean, I’ll be dead. I won’t care. There’s no way I could care. But thinking now, in a caring state, forward to that moment… I’d like them to remember laughter and good conversation.

brett william childs

To see more of Brett’s work, visit his instagram page.

A Thoughtful Exchange

In Conversation with Brett Childs

Brett Childs is a photographer and thinker, focused on the relationship between individuals and the larger groups that they constitute. Specifically, he is interested in what agency individuals possess in a world largely comprised of complex systems. The images he makes are always, in one way or another, about the individual. He strives to allow his subjects to be recognized, rather than just seen.

Interviewed by Liam Lezra | June 30, 2020

When did you first realize that you could explore and express abstract concepts through photography?

The curtain was pulled back when I took that first class and learned what an f-stop was. It was a light switch. I saw how it all worked and this giant shroud of mystery was removed. I started shooting. It became clear that I had a developed eye. I was making a good image, made like I had seen before. It was aesthetically pleasing, well-lit; it was what was expected.

I started asking, how do I make something that people can really feel when they look at it? I still don’t have a concrete answer for that. I found what became really important is how I choose my sitters. Or, if they are choosing me, how am I responding? How am I trying to create an image with them?

In a studio, I want to have a thoughtful exchange. Once that happens, there is a vulnerability. What I want is to form a connection and try to capture that connection; other people may not know what our conversation was about, but they can look at the image and feel an emotional experience.

TITLE

What kind of emotional experience do you want your viewer to have?

If I make an image that no one looks at, it’s never really finished.

I don’t want to color the internal conversation of the viewer, but I want to direct them. I try to make work that has a lot of entry-points. Once they are looking, they are doing a lot of work with what I put in front of them.

Often, the person I have in mind as the viewer is the person I am photographing. Everyone has a camera now. Everyone is having their picture taken. People are much more aware of what they think they look like. But really it’s because they see a camera and they have that same face they put on, and they see the pictures and say, “I don’t photograph well.” Okay, maybe. Maybe no one’s taken a good photograph of you.

It’s never that someone doesn’t photograph well. It’s that they don’t have any photographs of themselves that they like. I love when I’ve taken a picture and I show it to someone and they say, “Damn, I knew you were taking a picture, but when did this happen? Why didn’t I know it was going to be like this?”

I’m like, “Good. I hope you remember how this feels.”

How do you choose your subjects?

Usually, it’s people I’ve met. I’m interested in them as an individual. That’s how it starts. There’s some inkling or exchange I’ve had with them. Specifically for Against Monolith, the pool is limited to people of color, but it’s also people who have a very defined sense of individuality. Individuality is a big part of all of my images because we categorize things without even thinking about it. I’m interested in people who break out of categorization. It can be for a lot of reasons. I noticed that oftentimes it’s that someone has a very specific style.

The piece that is featured in Rough Cut, Julia, is a portrait of my sister. At that time, she had just started her Master’s Program in Social Work, specifically Critical Race Theory. She was hugely influential in this project because I love to read, so when she started her program the first thing I did was ask her to send me everything she was reading. Send your syllabi, all of your essays, everything.

Julia – from Against Monolith

She is such an incredibly smart and caring person. Social work is a rough job. She just decided she wanted to be the person giving back, and she’s doing it in a big way. She’s specifically focused on generational trauma. My conversations with her became the rock and foundation for Against Monolith. It helps that she had a very solid background, both in her own experience and in doing the work to try and understand it better. I was able to try and understand my own experience and integrate that.

What inspired you to create this series, Against Monolith?

The project looks at this big thing that is happening, and it looks at little ways that it is also happening. The big thing is, “Are we recognizing people of color?” That question is happening all the time; on a structural level, on a personal level, it’s always happening.

I am a photographer, so I am looking at the history of the medium and how it can support the thoughts I am having. I was interested in earlier photographic work that involved individuation and identity formation. So, I started obsessively trying to tear apart and understand what forms an individual, which is always related to another individual or a group. I wondered: how do you maintain individuality when you’re in a group?

Then I wondered, how do you affect change? What is the efficacy of change? What can you change, as an individual? I started looking deeper into the history of photography. There’s been some writing about the history of Kodak Films. Goddard was a filmmaker who proclaimed Kodak films racist in the 70s. He wouldn’t use them to shoot a project because they couldn’t reliably capture the skin tones of people of color.

I was also taking a deep dive into what’s called the Zone System, which was developed by Ansel Adams for photography. It’s kind of a pre-visualization system. When you’re looking at a scene you want to photograph it helps you map all the tones in that scene mentally so you can execute it technically. If you’re looking at the zone system on a chart of grays, Zone 10 is pure white. Zone 0 is pure black. Skin tone is Zone 5. Zone 3 is shadow with detail and Zone 8 is highlight with detail. Zone 6, as skin tone, is an inherently Caucasian skin tone.

The test print at Kodak was called a “Shirley Card,” It changed over the years. Had some color bars, a bowl of fruit, a red dress. It was always a white woman, though. You could try and print your own negative that was taken of a person of color until it looks right to your eye, but there wasn’t a way of calibrating it, so your skin tones would be all off.

Kodak knew it was a problem, it was brought up for decades, they didn’t change anything. Eventually, it was chocolate manufacturers and furniture makers who said, “We’re not getting the correct tones in our advertising. This needs to be changed.”

Kodak & Rochester was a behemoth of research and development, but it wasn’t until the late seventies or eighties that it became a priority. Then they pushed an advertising campaign for film that would be more accurate with darker skin tones, or just darker things. They said you could photograph a black horse at night.

The first multi-racial Shirley Cards came out in the nineties.

To me, this is a really interesting example of how complex racism can be. It doesn’t matter if Kodak was acting in a racist way, because the lived experience of people was the same. If you were a person of color who was trying to get your wedding photo taken, that was the grinder with Kodak. You have dark skin and a white dress. If you’re a photographer trying to capture the detail in the dress, all of her skin tone is gone. She just turns into kind of a black smear. No bride wants to spend all the money on a dress for her special day and see no detail in the pictures.

Was there someone at Kodak Films thinking, “Hey, let’s continue to marginalize a whole group of people?” No, of course not. They were probably thinking, “No one is taking pictures of shadows.” People are always taking pictures of stuff that’s lit.

It doesn’t really matter, though, because the end result is the same, which is, great, I can’t get my fucking picture taken.

How did studying history of Kodak and the zone system affect your work?

I didn’t just want to illustrate the thing that’s happened. I didn’t want to take photographs where people turned into a black smear. That’s not very interesting. So I thought a lot about what we expect of portraits. How can I subvert that? Is there any sort of template for how to go about that? We’re used to seeing and recognizing people in portraits. How can I subvert that familiarity? How can I stop it?

What if I make an image where it’s hard to see anything? But make it in a way where you really want to see it? Let’s make an image that rejects images. A black square. I thought of Carrie James Marshall, who is a painter, and he has a lot of paintings that are similar to this idea. The one that sticks in my mind is a nude male in a room at night and it’s just layers of black that he’s painted, so it’s really hard to see. I thought, what would that look like as a photograph? That meets what I was looking for, how do I make that happen? And then the whole technical thing is really very boring and extremely involved.

When I showed my advisor my first print he was like, “This is it.”

When did you start the project?

I started at the end of 2018. I was midway through one of my later undergrad terms. I pulled my first test-print in October, but the thought behind it wasn’t as fleshed out as I wanted it to be. I took nine months off from shooting to consider all of the different ways I can look at subject formation and how it ties into race. I started trying to survey a whole field looking at race. Eventually, I decided that with this project, and with all of my projects, I don’t really want answers. I want to ask better questions because if I give you what I think is the answer, it becomes a very simple exchange of right or wrong; I believe it or I don’t. I want to ask better questions so anyone who’s viewing the work can try and form their own answers. I’m not really looking to have an answer, I’m looking to create an experience.

Eventually, I got to the point where I’d thought enough about it and started shooting again. Instead of trying to offer an answer, “This is what it looks like. This is what it is.” There wasn’t that thing. Which is often true in life. We’re used to a narrative structure of things. It’s how we often tell and retell stories. But there’s not necessarily a definitive end. Maybe for an individual, you might die, and that’s kind of a definitive end, but your story continues on and there is no end.

TITLE

You don’t put a lot of work online.

It’s not how I want the images to be experienced. Ideally, I want them to be experienced in print. I’m very much into printed objects. I worked at a bookstore for twelve years, so it’s floating around in the DNA at this point. I would love for my work to be experienced in shows where you can come and talk to people, and have that sense of community and in-person conversation. Specifically with Against Monolith, it’s hard to show at all digitally. I have Julia hanging in our living room, and Claire and I talk all the time about how the light hits it. It activates it in space. At night you can hardly see it, but in the afternoon when the sunset is coming through the blinds it glows in a different way.

What struck me about Against Monolith was the element of time; I have to approach it and it takes time for my eyes to adjust and understand what I’m looking at.

Time is always an element of photography because you are capturing a piece of time. There are ways you can show time is happening, like motion blur or freezing motion, but it doesn’t really introduce that durational element.

Especially in an age when our relationship to imagery is fractions of seconds, when you put something in front of someone that they haven’t seen, it stops them. I have never shown someone this work to someone and not had it stop them. You become aware of your senses as you try to realize what it is you’re experiencing. It takes time.

Where do you go to find inspiration?

Conversations with people. A lot of films, books, music. Film is very inspirational to me. I sometimes have the same experiential feelings watching film that I would if I was looking at an installation, or a sculpture.

Where do you go to find hope?

I find hope in conversations with people. It’s not a specific hope, because the more specifically I try to think about hope, it’s out the window. We’re hopeless. Sometimes it can be hard to find the moment to really listen and really be present to someone.

TITLE

So, there’s hope in that deep listening and presence?

Yes, because I’m reminded that we’re not just groups, we are individuals. Once you start breaking into groups, on how many levels do you want to talk about disappointment? But that feeling changed with a lot of the protests that have happened lately. That was very hopeful. I didn’t think people would do it. Maybe it’s because we were sitting around and we weren’t at work, so we had the time to get up and say, “Fuck this.” I don’t know. But I was happy to see it. It was reassuring to see other people who care deeply, as well.

This is the most I’ve thought about hope in a long time. I need to sit and think about hope more than I do. It’s not really on my radar, maybe that needs to change.

How would you like to be remembered?

I don’t know if I have an attachment to being remembered. What do I want people to remember of me? Good conversation, maybe. I hope I made them think. Hopefully they’ll have good memories of well-intentioned conversations. I try to create good memories with people. I don’t want people thinking, “Fuck that guy.”

I mean, I’ll be dead. I won’t care. There’s no way I could care. But thinking now, in a caring state, forward to that moment… I’d like them to remember laughter and good conversation.

Brett William Childs