You Never Know Who’s Watching

In Conversation with Denice Frohman

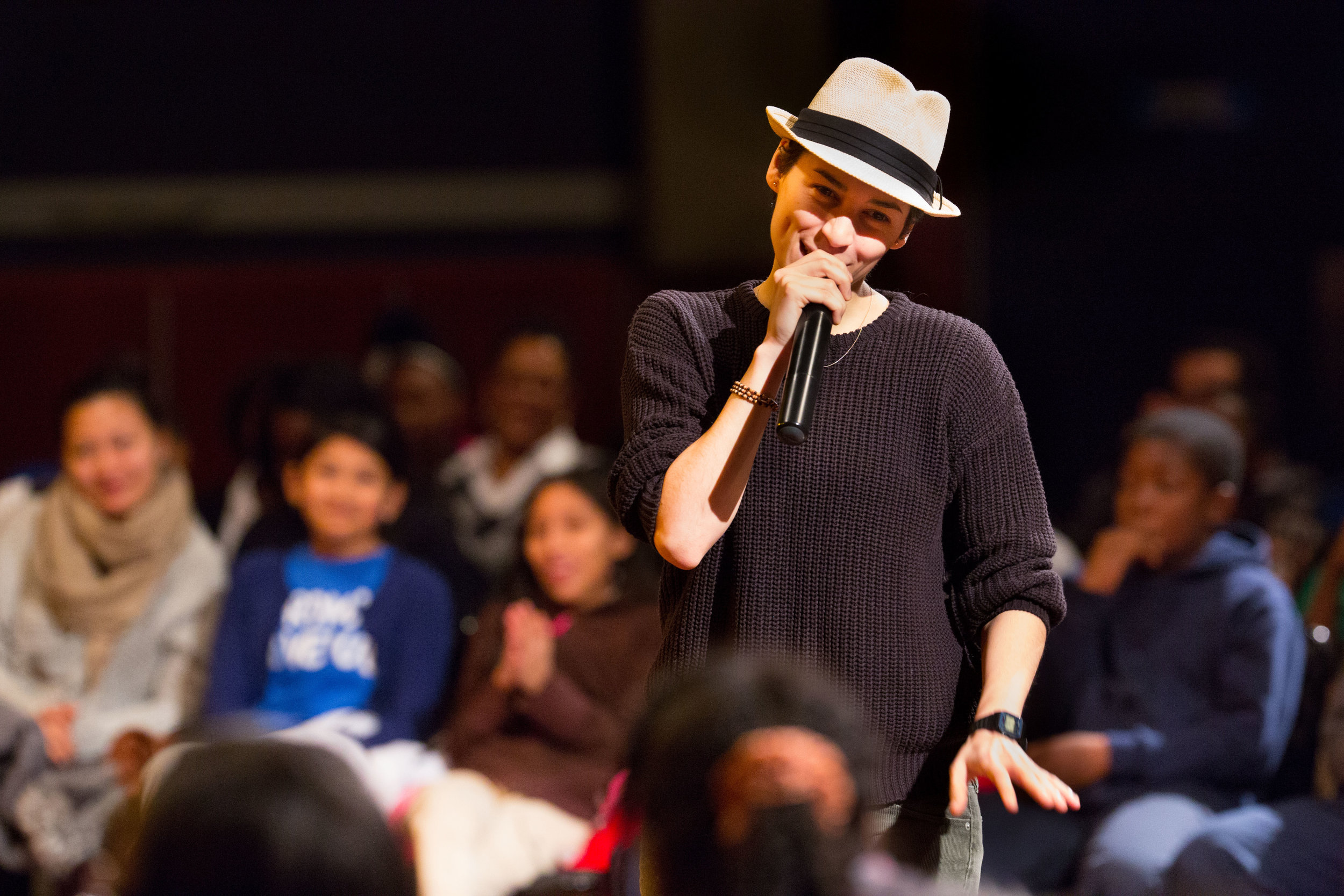

Photo by Nicholas Nichols

Denice Frohman is a poet, performer, and educator from New York City. A CantoMundo Fellow, she’s received residencies and awards from the National Association of Latino Arts & Cultures, Leeway Foundation, Blue Mountain Center, and Millay Colony. Her work has appeared in The BreakBeat Poets: LatiNext, Nepantla: An Anthology for Queer Poets of Color, The New York Times, ESPNW and garnered over 10 million views online. A former Women of the World Poetry Slam Champion, she’s featured on national and international stages from The White House to The Apollo, and over 200 colleges and universities. She co-organized #PoetsforPuertoRico and lives in Philadelphia.

Interviewed by Billy Lezra and Liam Lezra | September 4, 2020

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

We read that you didn’t really like poetry until you encountered the work of Gloria Anzaldúa in college, among other writers, like Sandra Cisneros and Cherríe Moraga. We were wondering what it was about Anzaldúa’s work in particular that spoke to you.

There are a number of poets and performers who really cracked open my idea of what poetry was and who poetry was for. I graduated from public high school in New York City with a dangerous misconception that Latinx and Latinos didn’t write poetry. I went to a really diverse school; still, because of the curriculum overall, I left believing that people like me don’t write and that we don’t have a place in poetry. When I got to college, I had a number of experiences both in and out of the classroom that revealed that lie. Gloria Anzaldúa was one of them. She was a Chicana lesbian feminist scholar poet who, like Audre Lorde, reclaimed all of her identities loudly and boldly. I remember reading Lorde at the same time as Anzaldúa and being like, “wow, I didn’t know that you could say that. I didn’t know that you could write in your full self like that.”

I read an essay that Anzaldúa published and co-edited with Cherríe Moraga. The essay is called “Speaking in Tongues,” where she is writing to other women of color writers. In this essay she asks a simple yet poignant question that I return to all the time: “Who gave us the permission to perform the act of writing?” I return to the question differently each time. I hear the question differently each time. I rest on that word permission and think: “how dare we write, how dare we speak, how dare we think we have something to say?” It is a radical question for those of us who have been convinced to be a smaller version of ourselves; to not take up space. I felt really seen by Anzaldúa’s work, especially as someone writing about the borderlands, not as a physical and arbitrary line—but this idea of the in-betweenness.

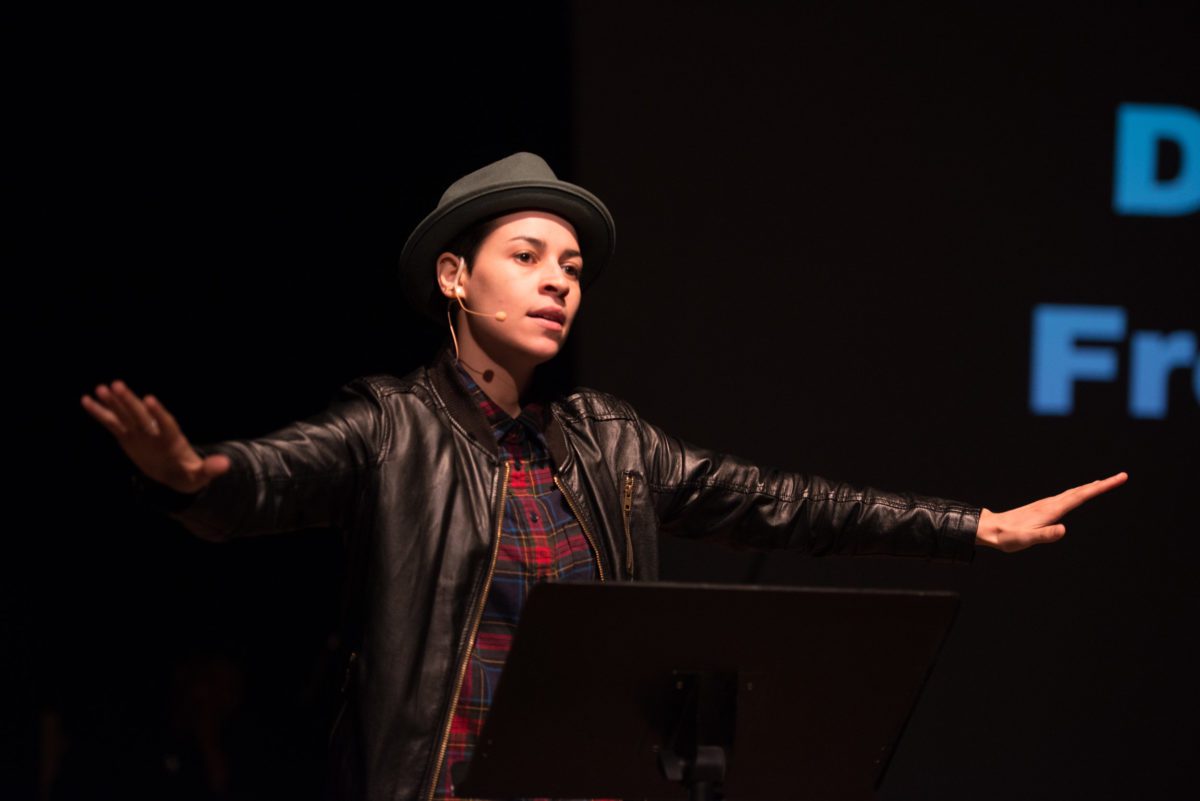

Brooklyn Museum & PEN America. Photograph © Alyza Enriquez

AnaLouise Keating, a scholar of her work, says that Anzaldúa is basically calling us a threshold people. I really identified with that for a number of reasons. I didn’t feel like my identity fit neatly in any particular place. So I found home and a harbor in Anzaldúa’s work. I felt seen.

One of the first things I read of Anzaldúa was the notion of la frontera being una herida abierta. There’s a liminal identity of never quite belonging.

I remember that section where she talks about how wild tongues can’t be tamed—they can only be cut out. I wanted to get that tattooed on my body for a solid five years. Those words completely changed how I saw language and what language could do. To see someone step so fully into themselves and claim that liminal space. We make a home where they say there is no home. Poetry puts its foot in that space that says there is no value, and pushes back.

I read that you said that poetry can subvert something that has been used against you to then use it for you. How and when did that come up for you in your work?

It started coming up for me before my work. It is something I learned on the playground, something I learned after school, wherever language was used. I grew up playing sports. I was around boys a lot. People cracked jokes on me and bullies would say things. I had to get good with my language, and have comebacks. I learned how to turn language that had been weaponized back on its head. Or finding other languages to use. Or maybe language was my body, and what I did when I was competing against them.

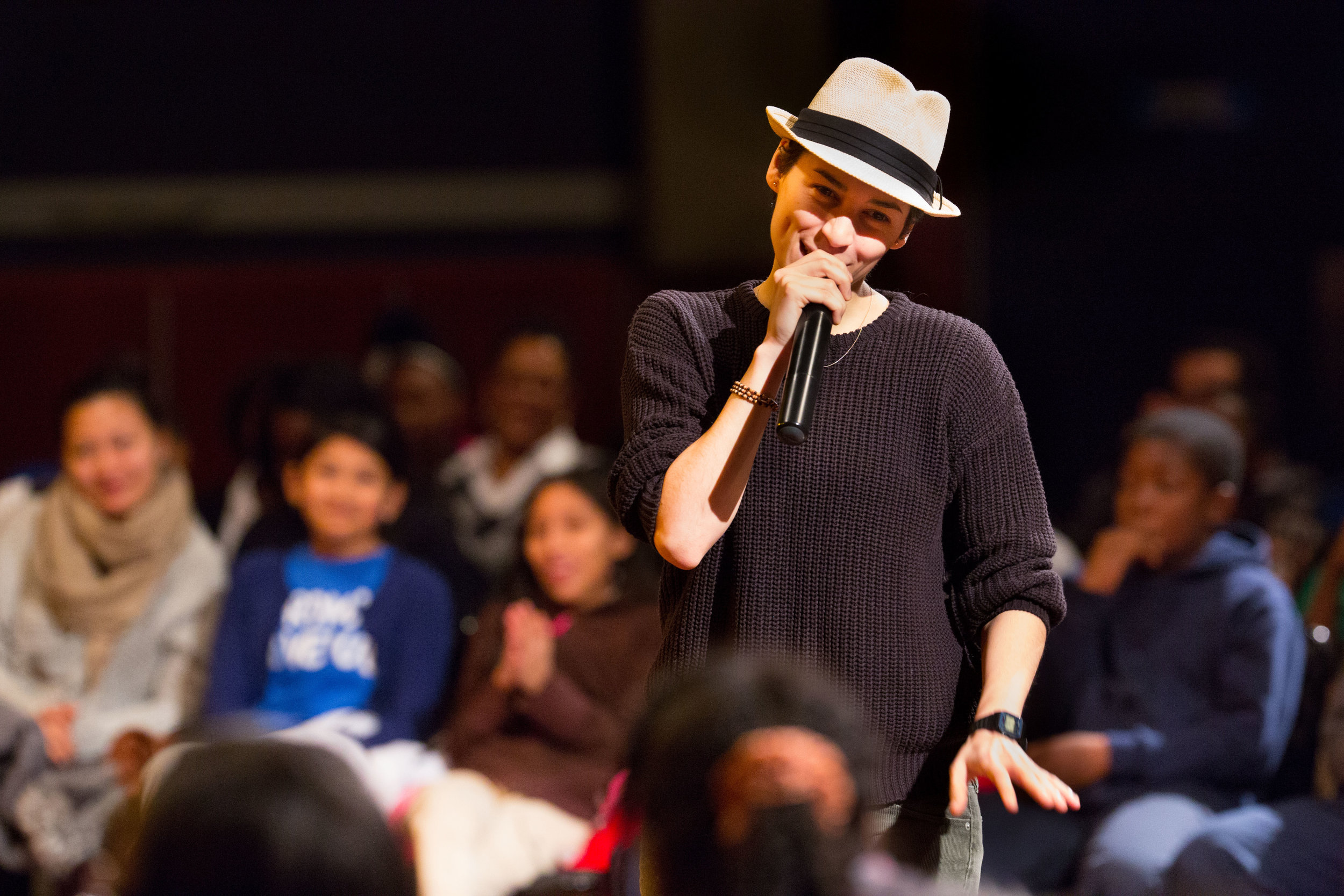

Photo by Conrad Erb

I learned this before poetry, which is why something felt familiar when I arrived at poetry. I had been playing with language already, I had been pushing back in my own ways. Poetry gave me a whole new set of creative tools to turn language on its head. And we see all the time how language is used to dehumanize marginalized communities. If you are going to violate or demean or oppress a community, you have to create a narrative that somehow justifies the dehumanization. We see this with immigrants, with communities of color, with Black and indigenous communities, with women, with trans folk, with Black trans women, with poor people. Language is used to create a narrative that says “you deserve this.” Poetry is inherently political for a number of reasons, but for that in particular. Poetry is taking that narrative that says, “your people are ugly, you have nothing to offer, you are weak, you are docile,” and pushing back and celebrating things others say are unworthy of being celebrated.

What is your creative process like?

It is something I think about a lot and it is something I am constantly revising; by revising, I mean remembering. Poetry is a very embodied practice for me. I write because I want to say the poems in my body, and I want to say them out loud. Oftentimes I am thinking or walking, and a line or an image will come. I don’t play basketball in a structured way anymore, but it is one of the ways I write. When I am shooting or dribbling, my body is in a particular rhythm, which means my subconscious is open. I remember Cherríe Moraga said: “Your subconscious is so much smarter than you.” My creative process is getting out of the way and listening, remembering, thinking, meditating, and, of course, reading.

This reminds me of the liminal space we were discussing earlier, and also what you said about poetry being situated between remembering and forgetting.

I still think I am sitting with that idea of poetry being what lives between remembering and forgetting. We are always vacillating between the two. I have to explore the stories that live in my body, what they are doing, and why they live there. One of my favorite poets, Cynthia Dewi Oka, said that: “Remembering is a revolutionary act.” In my family, it is really hard to get some of the stories of what our parents went through. If I don’t write them, I wonder what will be left in the archives. How will we be remembered?

When it comes to memory and cultural and ancestral memory, sometimes when you can’t get the story, you get the feeling. There are a lot of stories I don’t know because they are painful. A poem I wrote like “Doña Teresa and The Chicken,” where I am recalling a grief, and I am tracing a lineage of grief; I didn’t know I was doing that until I wrote the poem. I tried to forget the story, but I couldn’t, and I didn’t know why. I had to write it out because I come from women who feel too much to feel too much. These are women that are not going to sit down and have heart-to-hearts with you. They are going to love you deep and they are going to love you hard, and they will try to prepare you for a world that may not love you back. That is something I feel intimately. I was trying to trace that feeling.

[fusion_youtube id=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spBAF3fLhso&ab_channel=AdrianBrinkerhoffPoetryFoundation” alignment=”” width=”” height=”” autoplay=”false” api_params=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” css_id=”” /]

For you, what is the importance of writing and immortalizing these familial and ancestral stories?

The more I learn about Puerto Rican history, which is not taught in schools, the more I understand why my family is the way they are; why they feel the way they do; why they show up the way they do; why they say what they say; why they don’t say what they don’t say. It is a feeling of “we are not worthy” or “we don’t exist.” It is why we raise our flag with pride, and for me, pride and liberation are connected. For me, it is being proud and actively working toward our liberation as a community. When you understand the colonial relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico, you know that U.S. policies and Operation Bootstrap were responsible for the mass exodus [from Puerto Rico to the U.S.] in the fifties, which included my mom. That period of time between the fifties and seventies directly affected the trajectory of my family and many families.

La Ley de la Mordaza (“the Gag Law”) of 1948, said that in Puerto Rico you could not raise your flag. You could not sing songs of independence; you could not even hum them because you would be arrested. People were arrested for possessing a Puerto Rican flag. There were laws that prohibited Spanish. There were patterns of economic extraction, the extraction of resources, the suppression of Puerto Rican identity, and a campaign to assimilate. I feel that.

If you look at all the chants and all the songs: yo soy boricua pa que tu lo sepas. It sends chills down my spine. And I needed to understand the history of that bodily feeling that I have always had.

[fusion_youtube id=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fr4q3bj4dtE&ab_channel=TAINO” alignment=”” width=”” height=”” autoplay=”false” api_params=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” css_id=”” /]

The U.S. has had a colonial relationship with the island that is characterized by extraction, imposition, and dominance. I think that feeling reverberates throughout the diaspora because it is in the stories that we hear, and it is in the ways that we feel here, state-side, too. Unseen, and pushed toward assimilation. For me there is a clear line between what the writing is trying to do, what it is trying to push back against, and why it matters, especially if you understand the backdrop of this colonial relationship. Poetry for me meant that the poems can hold more than one thing at one time. The poems say, “you don’t have to make sense to make meaning.” The poems say, “your illegibilities have a place here. You’re still discoverable—I see you.”

How do you know when a poem is done?

I am going to give you Ada Limón’s answer. She said on Twitter: “I know a poem is almost done when I have to stand up and read it.”

What does family mean to you?

As a queer person, it means a lot of things. Family is not just who raised you, but who you choose to grow with. I have my chosen family and my family of origin. They are important to me and they serve different purposes, and entered my life at different times. I think that our family of origin is oftentimes married to a version of ourselves they have known this whole time. It is very hard, sometimes, for them to grow with you and understand that maybe you are different now.

In those moments in particular, I have been fortunate enough to have a chosen family who sees me and loves me, and who shows up. I think family is everything to me. It teaches me a lot about radical love. At least for me, it is a wild idea to be stretched so much in intimate familial relationships; even when I am stretched beyond myself, I know that we are going to come back to each other at some point. Only in our most intimate relationships can that elasticity exist. Hopefully it exists in a healthy way, which is the most important way. We each get to determine what works for us and what proximity we want to have with the people in our lives. And sometimes those are not easy choices, or choices at all.

How did you decide to get a Master’s in Education?

It happened by accident. I got the opportunity to teach a four-week high-school poetry class. It was in teaching that class where I fell in love with working with young people. It was immediate. It was one of the clearest signs that I received. I got my Master’s in Education shortly after that first class.

What was it about working with young people that brought that up for you?

What is the definition of love? I don’t know. I felt a purpose. I felt a calling. I am in tune to my purpose and deeply listening to the moments where life says, “yes, here.” And I think life said “yes, here,” not because I think I have something to give, but because I deeply believe in the radical process of learning together. I believe in relationships not as transactions, but as spaces for transformation. I recalled moments in my own public school education where I wish I had been introduced to more authors of color. And more LGBTQ authors. And I felt like perhaps this is one way that I can change or impact their educational experiences, even if it is just through one book or one course. How do I create an environment where perhaps they might one day stumble on a poem that makes them feel seen?

What is the best piece of advice you have received?

One of the best pieces of advice I received was from my father. He said, “you never know who is watching.” At the time I was trying to get an athletic scholarship. Sometimes there would be 100 people in the stands, sometimes there would be two people. During the summer tournaments there might be one coach, or five coaches. And my dad always said: “leave it all out there. You never know who is watching.” I absolutely take that with me now, whether I am performing in front of three people or 300 people.

Where do you go to find hope?

These days I’ve been turning to nature. I have been taking walks in my neighborhood; I stop for the sunflowers. Or, if I am by the ocean, I’ll notice the moon. I’ll just look at all the trees and the flowers and the green space. If I am in nature, I am in awe of all that I don’t know, all that still exists in spite of us. And how gentle that rebirth is; how generative our natural world is. We need to show up and take radical steps to treat this planet a whole lot better and care for the land, the water, and the air. I think the pandemic slowed down time, in a way. It created a pause to look at the smallest things. I think the more connected to the land I can be, the more connected I can be to myself. Something about that makes me feel like a more whole person. So nature is where I turn for hope. Like, “how are you still here?” Or, “how are you growing back already? How did you do that?” It tells me that there is something beyond what I can see.

What are the qualities that you look for in a friend?

Integrity. And an orientation toward healing. Somebody who is curious about the world.

What does integrity mean to you?

How do you move when you think nobody is watching? How do you move in space? Are you moving for self or are you moving with community? It goes hand-in-hand with healing. Sometimes we walk out of integrity when we are wounded. The more connected I am to myself, the more aware I am of my growth and my edges, the more I can build a moral compass that guides me with a clear sense of who I want to be, and the energy I want to put in the world. Whether or not somebody is watching, I want to always walk with integrity.

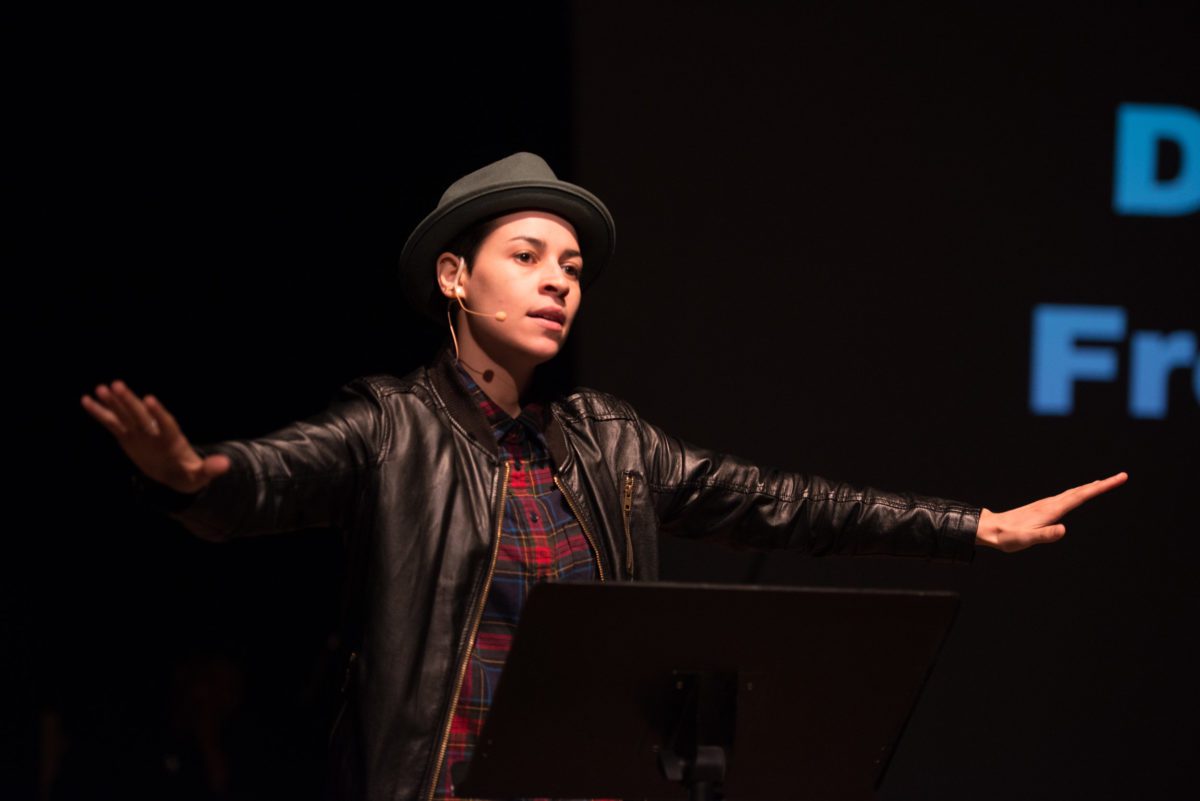

Photo by Johanna Austin

How would you like to be remembered?

This makes me think of Mary Ruefle. She wrote “Madness, Rack and Honey.” She says: “Some languages are so constructed—English among them—that we each only really speak one sentence in our lifetime. That sentence begins with your first words, toddling around the kitchen, and ends with your last words right before you step into the limousine, or in a nursing home, the night-duty attendant vaguely on hand. Or, if you are blessed, they are heard by someone who knows you and loves you and will be sorry to hear the sentence end.”

I think that is how I want to be remembered. I hope that I give enough love in the world that people will be sad to hear the sentence end. But that they might carry my life-long sentence. And that my life-long sentence ignites their own life-long sentence. I want to be remembered as someone who deeply cares about community, who deeply cares about moving with, and alongside community. I think about Aracelis Girmay. She was sharing her work and asked the audience, “who do you walk alongside of or because of?”

I think about all those people that I walk alongside of. And I would like to imagine a room full of people who would name me as someone that they walk alongside of and because of. What are the stories they would tell? I hope that in those stories I gave a damn, and that I cared deeply about young people, and about the power of poetry to invite us to fall in love with the power of our voices. And that I believed in our language and in our people and in my people; that I believed in us. And hopefully I saved a little bit of that belief for myself, too. And that it mattered. That’s where I want to live—where it matters.

To learn more about Denice and her work, visit her website.

You Never Know Who’s Watching

In Conversation with Denice Frohman

Photo by Nicholas Nichols

Denice Frohman is a poet, performer, and educator from New York City. A CantoMundo Fellow, she’s received residencies and awards from the National Association of Latino Arts & Cultures, Leeway Foundation, Blue Mountain Center, and Millay Colony. Her work has appeared in The BreakBeat Poets: LatiNext, Nepantla: An Anthology for Queer Poets of Color, The New York Times, ESPNW and garnered over 10 million views online. A former Women of the World Poetry Slam Champion, she’s featured on national and international stages from The White House to The Apollo, and over 200 colleges and universities. She co-organized #PoetsforPuertoRico and lives in Philadelphia.

Interviewed by Billy Lezra and Liam Lezra | September 4, 2020

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

We read that you didn’t really like poetry until you encountered the work of Gloria Anzaldúa in college, among other writers, like Sandra Cisneros and Cherríe Moraga. We were wondering what it was about Anzaldúa’s work in particular that spoke to you.

There are a number of poets and performers who really cracked open my idea of what poetry was and who poetry was for. I graduated from public high school in New York City with a dangerous misconception that Latinx and Latinos didn’t write poetry. I went to a really diverse school; still, because of the curriculum overall, I left believing that people like me don’t write and that we don’t have a place in poetry. When I got to college, I had a number of experiences both in and out of the classroom that revealed that lie. Gloria Anzaldúa was one of them. She was a Chicana lesbian feminist scholar poet who, like Audre Lorde, reclaimed all of her identities loudly and boldly. I remember reading Lorde at the same time as Anzaldúa and being like, “wow, I didn’t know that you could say that. I didn’t know that you could write in your full self like that.”

I read an essay that Anzaldúa published and co-edited with Cherríe Moraga. The essay is called “Speaking in Tongues,” where she is writing to other women of color writers. In this essay she asks a simple yet poignant question that I return to all the time: “Who gave us the permission to perform the act of writing?” I return to the question differently each time. I hear the question differently each time. I rest on that word permission and think: “how dare we write, how dare we speak, how dare we think we have something to say?” It is a radical question for those of us who have been convinced to be a smaller version of ourselves; to not take up space. I felt really seen by Anzaldúa’s work, especially as someone writing about the borderlands, not as a physical and arbitrary line—but this idea of the in-betweenness.

Brooklyn Museum & PEN America. Photograph © Alyza Enriquez

AnaLouise Keating, a scholar of her work, says that Anzaldúa is basically calling us a threshold people. I really identified with that for a number of reasons. I didn’t feel like my identity fit neatly in any particular place. So I found home and a harbor in Anzaldúa’s work. I felt seen.

One of the first things I read of Anzaldúa was the notion of la frontera being una herida abierta. There’s a liminal identity of never quite belonging.

I remember that section where she talks about how wild tongues can’t be tamed—they can only be cut out. I wanted to get that tattooed on my body for a solid five years. Those words completely changed how I saw language and what language could do. To see someone step so fully into themselves and claim that liminal space. We make a home where they say there is no home. Poetry puts its foot in that space that says there is no value, and pushes back.

I read that you said that poetry can subvert something that has been used against you to then use it for you. How and when did that come up for you in your work?

It started coming up for me before my work. It is something I learned on the playground, something I learned after school, wherever language was used. I grew up playing sports. I was around boys a lot. People cracked jokes on me and bullies would say things. I had to get good with my language, and have comebacks. I learned how to turn language that had been weaponized back on its head. Or finding other languages to use. Or maybe language was my body, and what I did when I was competing against them.

Photo by Conrad Erb

I learned this before poetry, which is why something felt familiar when I arrived at poetry. I had been playing with language already, I had been pushing back in my own ways. Poetry gave me a whole new set of creative tools to turn language on its head. And we see all the time how language is used to dehumanize marginalized communities. If you are going to violate or demean or oppress a community, you have to create a narrative that somehow justifies the dehumanization. We see this with immigrants, with communities of color, with Black and indigenous communities, with women, with trans folk, with Black trans women, with poor people. Language is used to create a narrative that says “you deserve this.” Poetry is inherently political for a number of reasons, but for that in particular. Poetry is taking that narrative that says, “your people are ugly, you have nothing to offer, you are weak, you are docile,” and pushing back and celebrating things others say are unworthy of being celebrated.

What is your creative process like?

It is something I think about a lot and it is something I am constantly revising; by revising, I mean remembering. Poetry is a very embodied practice for me. I write because I want to say the poems in my body, and I want to say them out loud. Oftentimes I am thinking or walking, and a line or an image will come. I don’t play basketball in a structured way anymore, but it is one of the ways I write. When I am shooting or dribbling, my body is in a particular rhythm, which means my subconscious is open. I remember Cherríe Moraga said: “Your subconscious is so much smarter than you.” My creative process is getting out of the way, listening, remembering, thinking, meditating, and, of course, reading.

This reminds me of the liminal space we were discussing earlier, and also what you said about poetry being situated between remembering and forgetting.

I still think I am sitting with that idea of poetry being what lives between remembering and forgetting. We are always vacillating between the two. I have to explore the stories that live in my body, what they are doing, and why they live there. One of my favorite poets, Cynthia Dewi Oka, said that: “Remembering is a revolutionary act.” In my family, it is really hard to get some of the stories of what our parents went through. If I don’t write them, I wonder what will be left in the archives. How will we be remembered?

When it comes to memory and cultural and ancestral memory, sometimes when you can’t get the story, you get the feeling. There are a lot of stories I don’t know because they are painful. A poem I wrote like “Doña Teresa and The Chicken,” where I am recalling a grief, and I am tracing a lineage of grief; I didn’t know I was doing that until I wrote the poem. I tried to forget the story, but I couldn’t, and I didn’t know why. I had to write it out because I come from women who feel too much to feel too much. These are women that are not going to sit down and have heart-to-hearts with you. They are going to love you deep and they are going to love you hard, and they will try to prepare you for a world that may not love you back. That is something I feel intimately. I was trying to trace that feeling.

[fusion_youtube id=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spBAF3fLhso&ab_channel=AdrianBrinkerhoffPoetryFoundation” alignment=”” width=”” height=”” autoplay=”false” api_params=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” css_id=”” /]

For you, what is the importance of writing and immortalizing these familial and ancestral stories?

The more I learn about Puerto Rican history, which is not taught in schools, the more I understand why my family is the way they are; why they feel the way they do; why they show up the way they do; why they say what they say; why they don’t say what they don’t say. It is a feeling of “we are not worthy” or “we don’t exist.” It is why we raise our flag with pride, and for me, pride and liberation are connected. For me, it is being proud and actively working toward our liberation as a community. When you understand the colonial relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico, you know that U.S. policies and Operation Bootstrap were responsible for the mass exodus [from Puerto Rico to the U.S.] in the fifties, which included my mom. That period of time between the fifties and seventies directly affected the trajectory of my family and many families.

La Ley de la Mordaza (“the Gag Law”) of 1948, said that in Puerto Rico you could not raise your flag. You could not sing songs of independence; you could not even hum them because you would be arrested.

People were arrested for possessing a Puerto Rican flag. There were laws that prohibited Spanish. There were patterns of economic extraction, the extraction of resources, the suppression of Puerto Rican identity, and a campaign to assimilate. I feel that.

If you look at all the chants and all the songs: yo soy boricua pa que tu lo sepas. It sends chills down my spine. And I needed to understand the history of that bodily feeling that I have always had.

[fusion_youtube id=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fr4q3bj4dtE&ab_channel=TAINO” alignment=”” width=”” height=”” autoplay=”false” api_params=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” css_id=”” /]

The U.S. has had a colonial relationship with the island that is characterized by extraction, imposition, and dominance. I think that feeling reverberates throughout the diaspora because it is in the stories that we hear, and it is in the ways that we feel here, state-side, too. Unseen, and pushed toward assimilation. For me there is a clear line between what the writing is trying to do, what it is trying to push back against, and why it matters, especially if you understand the backdrop of this colonial relationship. Poetry for me meant that the poems can hold more than one thing at one time. The poems say, “you don’t have to make sense to make meaning.” The poems say, “your illegibilities have a place here. You’re still discoverable—I see you.”

How do you know when a poem is done?

I am going to give you Ada Limón’s answer. She said on Twitter: “I know a poem is almost done when I have to stand up and read it.”

What does family mean to you?

As a queer person, it means a lot of things. Family is not just who raised you, but who you choose to grow with. I have my chosen family and my family of origin. They are important to me and they serve different purposes, and entered my life at different times. I think that our family of origin is oftentimes married to a version of ourselves they have known this whole time. It is very hard, sometimes, for them to grow with you and understand that maybe you are different now.

In those moments in particular, I have been fortunate enough to have a chosen family who sees me and loves me, and who shows up. I think family is everything to me. It teaches me a lot about radical love. At least for me, it is a wild idea to be stretched so much in intimate familial relationships; even when I am stretched beyond myself, I know that we are going to come back to each other at some point. Only in our most intimate relationships can that elasticity exist. Hopefully it exists in a healthy way, which is the most important way. We each get to determine what works for us and what proximity we want to have with the people in our lives. And sometimes those are not easy choices, or choices at all.

How did you decide to get a Master’s in Education?

It happened by accident. I got the opportunity to teach a four-week high-school poetry class. It was in teaching that class where I fell in love with working with young people. It was immediate. It was one of the clearest signs that I received. I got my Master’s in Education shortly after that first class.

What was it about working with young people that brought that up for you?

What is the definition of love? I don’t know. I felt a purpose. I felt a calling. I am in tune to my purpose and deeply listening to the moments where life says, “yes, here.” And I think life said “yes, here,” not because I think I have something to give, but because I deeply believe in the radical process of learning together. I believe in relationships not as transactions, but as spaces for transformation. I recalled moments in my own public school education where I wish I had been introduced to more authors of color. And more LGBTQ authors. And I felt like perhaps this is one way that I can change or impact their educational experiences, even if it is just through one book or one course. How do I create an environment where perhaps they might one day stumble on a poem that makes them feel seen?

What is the best piece of advice you have received?

One of the best pieces of advice I received was from my father. He said, “you never know who is watching.” At the time I was trying to get an athletic scholarship. Sometimes there would be 100 people in the stands, sometimes there would be two people. During the summer tournaments there might be one coach, or five coaches. And my dad always said: “leave it all out there. You never know who is watching.” I absolutely take that with me now, whether I am performing in front of three people or 300 people.

Where do you go to find hope?

These days I’ve been turning to nature. I have been taking walks in my neighborhood; I stop for the sunflowers. Or, if I am by the ocean, I’ll notice the moon. I’ll just look at all the trees and the flowers and the green space. If I am in nature, I am in awe of all that I don’t know, all that still exists in spite of us. And how gentle that rebirth is; how generative our natural world is. We need to show up and take radical steps to treat this planet a whole lot better and care for the land, the water, and the air. I think the pandemic slowed down time, in a way. It created a pause to look at the smallest things. I think the more connected to the land I can be, the more connected I can be to myself. Something about that makes me feel like a more whole person. So nature is where I turn for hope. Like, “how are you still here?” Or, “how are you growing back already? How did you do that?” It tells me that there is something beyond what I can see.

What are the qualities that you look for in a friend?

Integrity. And an orientation toward healing. Somebody who is curious about the world.

What does integrity mean to you?

How do you move when you think nobody is watching? How do you move in space? Are you moving for self or are you moving with community? It goes hand-in-hand with healing. Sometimes we walk out of integrity when we are wounded. The more connected I am to myself, the more aware I am of my growth and my edges, the more I can build a moral compass that guides me with a clear sense of who I want to be, and the energy I want to put in the world. Whether or not somebody is watching, I want to always walk with integrity.

Photo by Johanna Austin

How would you like to be remembered?

This makes me think of Mary Ruefle. She wrote “Madness, Rack and Honey.” She says: “Some languages are so constructed—English among them—that we each only really speak one sentence in our lifetime. That sentence begins with your first words, toddling around the kitchen, and ends with your last words right before you step into the limousine, or in a nursing home, the night-duty attendant vaguely on hand. Or, if you are blessed, they are heard by someone who knows you and loves you and will be sorry to hear the sentence end.”

I think that is how I want to be remembered. I hope that I give enough love in the world that people will be sad to hear the sentence end. But that they might carry my life-long sentence. And that my life-long sentence ignites their own life-long sentence. I want to be remembered as someone who deeply cares about community, who deeply cares about moving with, and alongside community. I think about Aracelis Girmay. She was sharing her work and asked the audience, “who do you walk alongside of or because of?”

I think about all those people that I walk alongside of. And I would like to imagine a room full of people who would name me as someone that they walk alongside of and because of. What are the stories they would tell? I hope that in those stories I gave a damn, and that I cared deeply about young people, and about the power of poetry to invite us to fall in love with the power of our voices. And that I believed in our language and in our people and in my people; that I believed in us. And hopefully I saved a little bit of that belief for myself, too. And that it mattered. That’s where I want to live—where it matters.