This month we offer water, radiance, and trees.

Next month we stay

TENDER

Submission guidelines can be found here.

The Act of Living Includes Hope

In Conversation with Silas House

Silas House is the New York Times bestselling author of seven novels, one book of creative nonfiction, and three plays. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Time, the New York Times, the Advocate, Garden & Gun, and other publications. A former commentator for NPR’s All Things Considered, House is the winner of two Nautilus Awards, the Storylines Prize from the NAV/New York Public Library, an E. B. White Award, and the Southern Book Prize. He has been appointed as the poet laureate of Kentucky for the years 2023-2025.

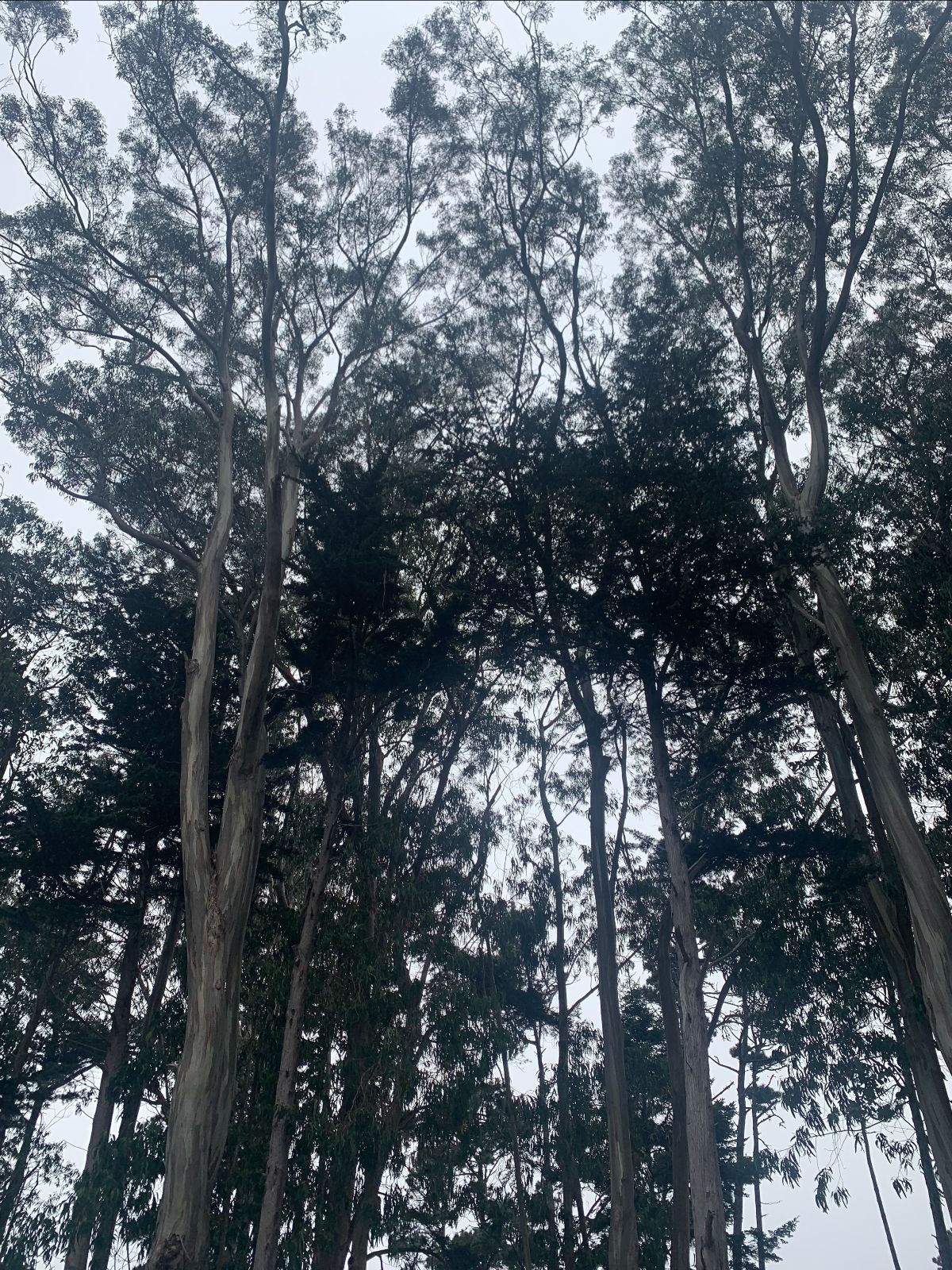

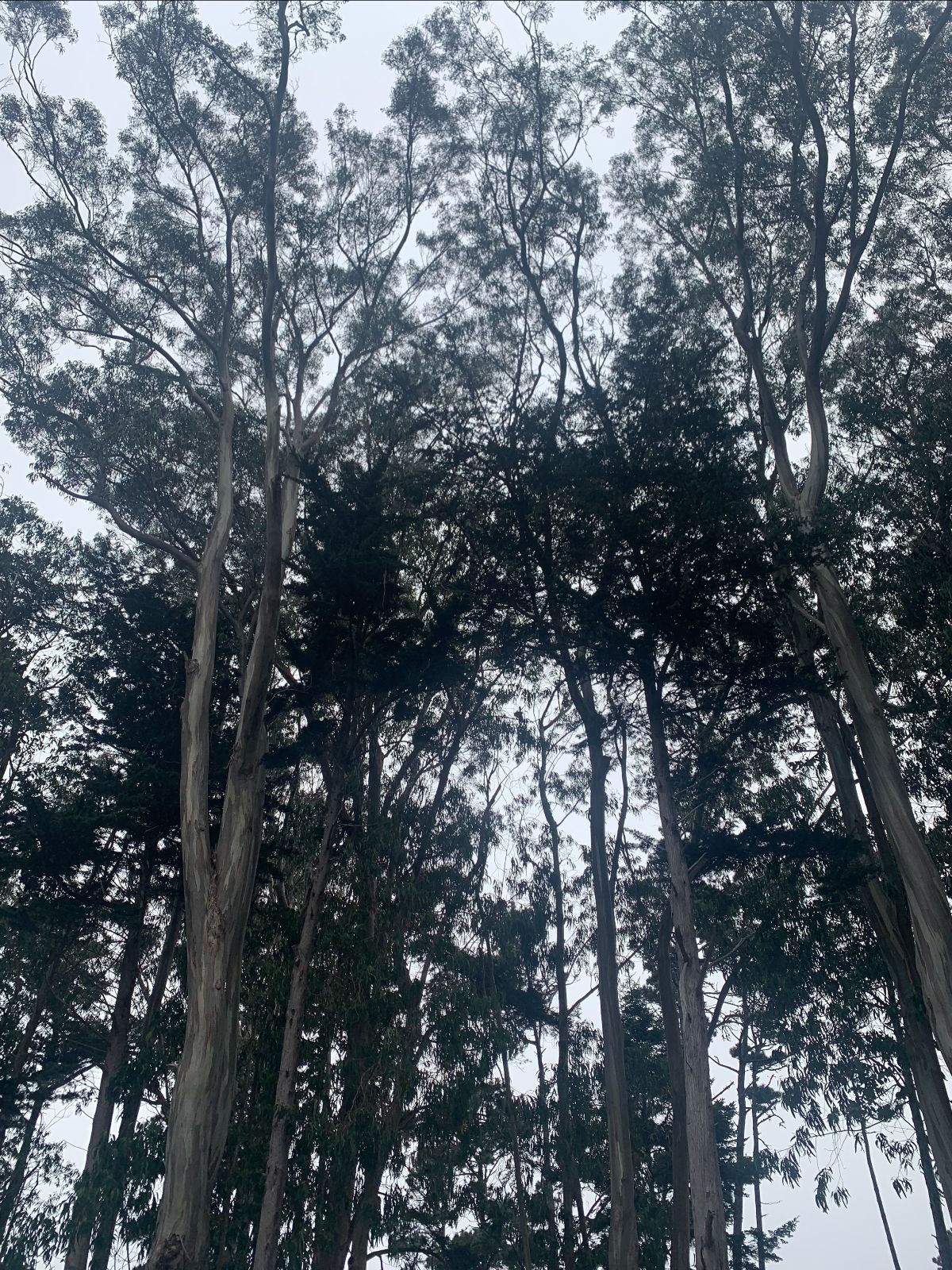

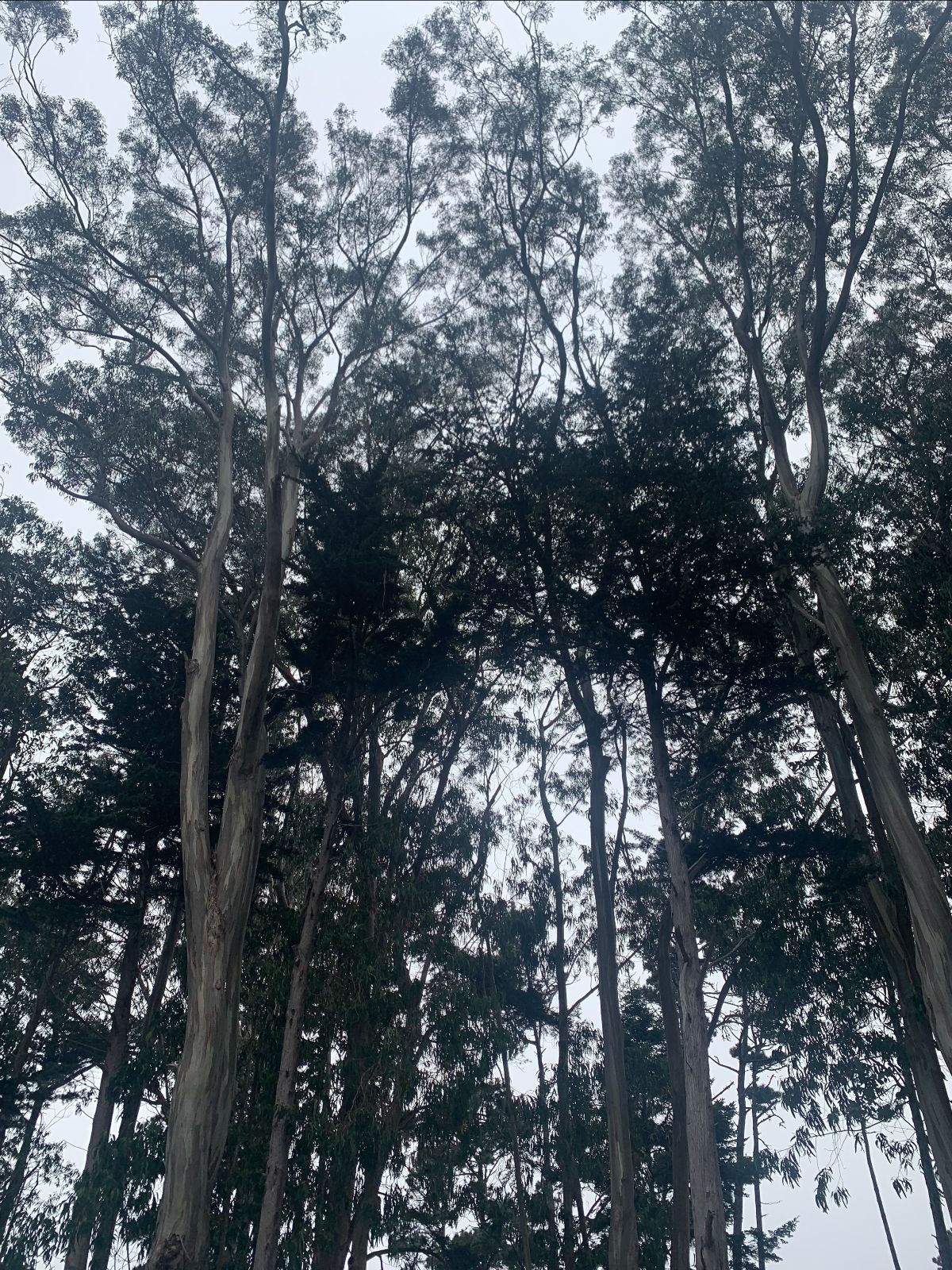

trees

Before he and I broke up, we lived on the south side across from a liquor store. It had bullet-proof glass and a CCTV screen that let you see yourself from four angles. Outside was an oak tree. The fall leaves hung in lazy brown, carelessly striking the heads of drunk passersby. Most of the leaves had not succumbed to gravity by the time his bags were packed and my rent doubled. I wondered what those branches looked like bare. Maybe as naked as his arms, or coarse as his legs.

Before I was evicted, I sublet on the west side under the elevated train tracks. There were sleeping cherry blossoms in the park about ten blocks away. I walked there every day. The snow dusted the park gates and the branches like expired sugar. But before it could melt and stir the pink to life, I got a knock on the door. Standing there was a cop with a surly mustache and a court document in hand.

Before I was denied unemployment benefits, I crashed on a couch on the far east side where there are only two take-out places. One is closed now, I think. I slept in the basement but if I stood on the toilet I could see the trunk of a gingko tree through a small window. It didn’t open, but there was enough light to see those buds graze the air. I read the letter from the city standing on that toilet. I know what gingko leaves look like, but only from pictures.

Before I moved to the shelter, I shared a bed with the guy who took care of me. I don’t remember what was nearby. Between the bars on the window I could see a single maple tree on our stretch of the block. It had red stems, teasing me of its crimson glory just a few months away. It held out on me all summer. I couldn’t hold out on anyone who came into that room. My first time trying was my last night there.

It’s been a while since. Two more springs have passed.

Today I realized it. As I strolled by my favorite corner store and the lady walking her ancient Chihuahua and the mural of a local legend, I saw it: the elm tree, steps in front of my stoop. I had seen its verdant fingers in summer splay. I had stepped on its fallen yellow autumn dress. I had scooped snow off its wintry roots. And now I can feel its bark, as old as I am young, hiding its ringed secrets, but promising me green again soon. I have known this tree in all its seasons.

Now repeating its cycle, I have escaped mine.

Patrick Johnson is an emerging, Queer poet from Queens, New York. He is a public school science teacher and labor union advocate. His poetry draws from many themes, often inspired by human history, loss, and family. He facilitates a bi-weekly poetry workshop, and enjoys supporting other poets in their artistic journeys.

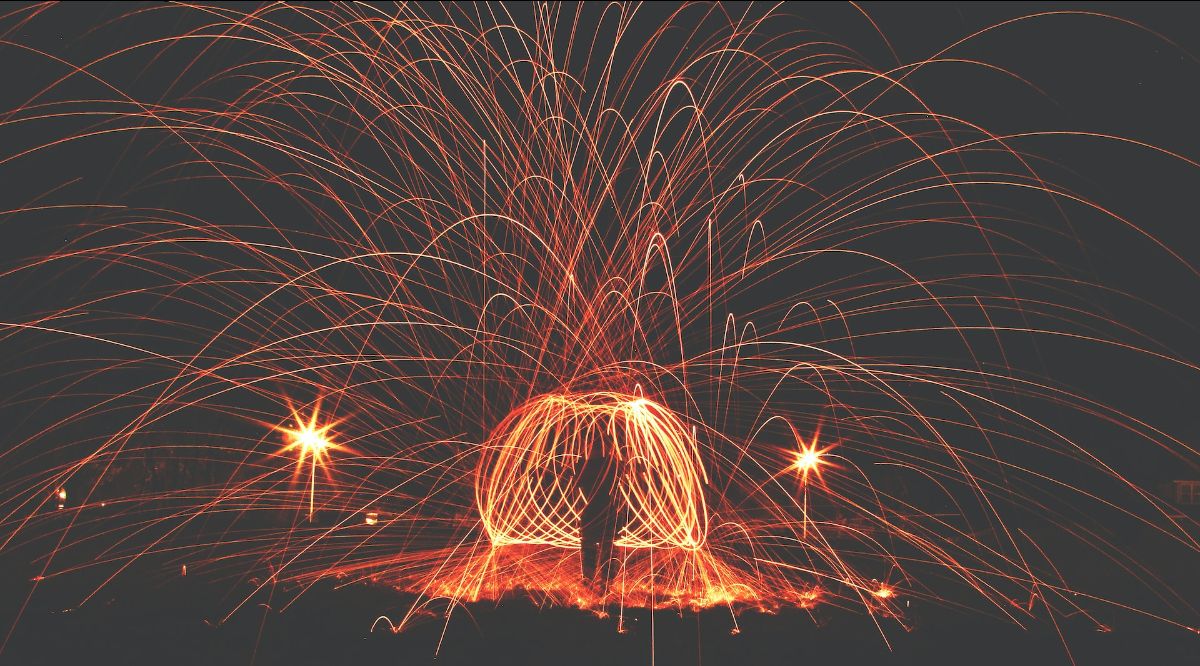

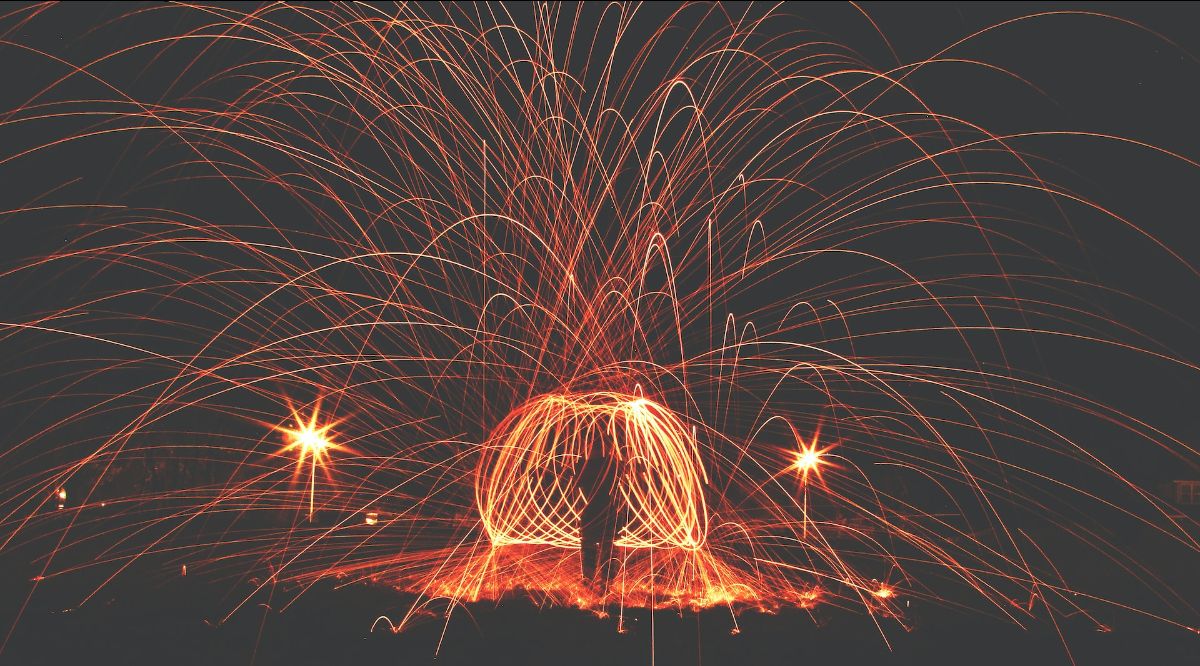

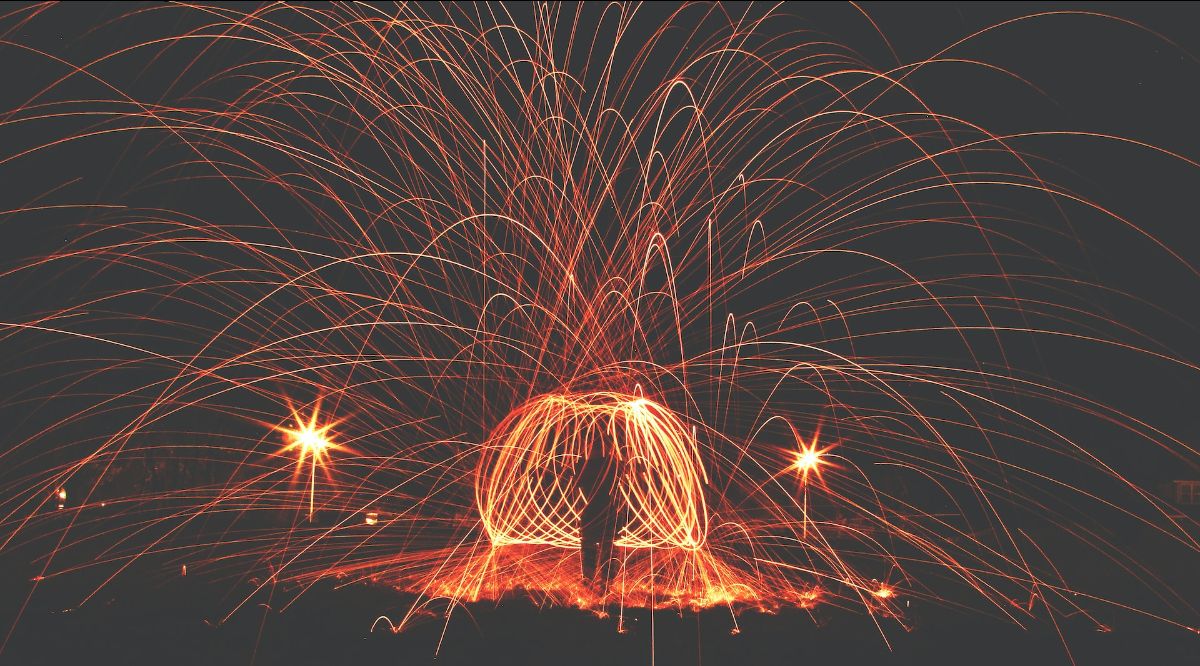

Radiance

in my sleep, I cleave from my ruin like an

orphan does to the relic of parental love—

this is how I ferry into light, into what I

lack the body to hold. I am at the extreme

of the world, suspended in silence, clinging

onto ashes, in search of what got burnt. I am

everything that follows “but” in a sentence.

light looks good on me, but my body is a sieve;

everything passes through without staying, like

water emptied into a basket, like a mother’s

prayer on the route to God’s abode. call this

a special kind of grace: the closest I have

come to light is in a gospel song fraying with

the wind from my neighbor’s window. but,

tonight, I will ride the storm, feast on its

countenance & soften it with the tide. today,

I am holding the promise of water. I am

what my generation returns to as hope. I am

the water to bloom the flowers wilting on the

acres of their mouths, the wind to fly their forked

prayers to the stars, to God’s ears. I shall hold

survival by its teeth as a baby does to a

nipple, scurrying in its radiance. today, when the night

comes, I shall chase it; let the light that would

precede it be mine. perhaps, it might stay.

Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi, THE PLOB, TPC V, is a budding poet, an essayist and an aspiring researcher from Kwara state, Nigeria. He is a Best Of The Net Nominee and a second place winner of the first edition of Hassan Sulaiman Gimba Esq Poetry Prize.

This month we offer water, radiance, and trees.

Next month we stay

TENDER

Submission guidelines can be found here.

The Act of Living Includes Hope

In Conversation with Silas House

Silas House is the New York Times bestselling author of seven novels, one book of creative nonfiction, and three plays. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Time, the New York Times, the Advocate, Garden & Gun, and other publications. A former commentator for NPR’s All Things Considered, House is the winner of two Nautilus Awards, the Storylines Prize from the NAV/New York Public Library, an E. B. White Award, and the Southern Book Prize. He has been appointed as the poet laureate of Kentucky for the years 2023-2025.

trees

Before he and I broke up, we lived on the south side across from a liquor store. It had bullet-proof glass and a CCTV screen that let you see yourself from four angles. Outside was an oak tree. The fall leaves hung in lazy brown, carelessly striking the heads of drunk passersby. Most of the leaves had not succumbed to gravity by the time his bags were packed and my rent doubled. I wondered what those branches looked like bare. Maybe as naked as his arms, or coarse as his legs.

Before I was evicted, I sublet on the west side under the elevated train tracks. There were sleeping cherry blossoms in the park about ten blocks away. I walked there every day. The snow dusted the park gates and the branches like expired sugar. But before it could melt and stir the pink to life, I got a knock on the door. Standing there was a cop with a surly mustache and a court document in hand.

Before I was denied unemployment benefits, I crashed on a couch on the far east side where there are only two take-out places. One is closed now, I think. I slept in the basement but if I stood on the toilet I could see the trunk of a gingko tree through a small window. It didn’t open, but there was enough light to see those buds graze the air. I read the letter from the city standing on that toilet. I know what gingko leaves look like, but only from pictures.

Before I moved to the shelter, I shared a bed with the guy who took care of me. I don’t remember what was nearby. Between the bars on the window I could see a single maple tree on our stretch of the block. It had red stems, teasing me of its crimson glory just a few months away. It held out on me all summer. I couldn’t hold out on anyone who came into that room. My first time trying was my last night there.

It’s been a while since. Two more springs have passed.

Today I realized it. As I strolled by my favorite corner store and the lady walking her ancient Chihuahua and the mural of a local legend, I saw it: the elm tree, steps in front of my stoop. I had seen its verdant fingers in summer splay. I had stepped on its fallen yellow autumn dress. I had scooped snow off its wintry roots. And now I can feel its bark, as old as I am young, hiding its ringed secrets, but promising me green again soon. I have known this tree in all its seasons.

Now repeating its cycle, I have escaped mine.

Patrick Johnson is an emerging, Queer poet from Queens, New York. He is a public school science teacher and labor union advocate. His poetry draws from many themes, often inspired by human history, loss, and family. He facilitates a bi-weekly poetry workshop, and enjoys supporting other poets in their artistic journeys.

Radiance

in my sleep, I cleave from my ruin like an

orphan does to the relic of parental love—

this is how I ferry into light, into what I

lack the body to hold. I am at the extreme

of the world, suspended in silence, clinging

onto ashes, in search of what got burnt. I am

everything that follows “but” in a sentence.

light looks good on me, but my body is a sieve;

everything passes through without staying, like

water emptied into a basket, like a mother’s

prayer on the route to God’s abode. call this

a special kind of grace: the closest I have

come to light is in a gospel song fraying with

the wind from my neighbor’s window. but,

tonight, I will ride the storm, feast on its

countenance & soften it with the tide. today,

I am holding the promise of water. I am

what my generation returns to as hope. I am

the water to bloom the flowers wilting on the

acres of their mouths, the wind to fly their forked

prayers to the stars, to God’s ears. I shall hold

survival by its teeth as a baby does to a

nipple, scurrying in its radiance. today, when the night

comes, I shall chase it; let the light that would

precede it be mine. perhaps, it might stay.

Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi, THE PLOB, TPC V, is a budding poet, an essayist and an aspiring researcher from Kwara state, Nigeria. He is a Best Of The Net Nominee and a second place winner of the first edition of Hassan Sulaiman Gimba Esq Poetry Prize.

Sign up to receive a new issue of Rough Cut Press on the first of each month.

We will never share your contact information without explicit permission.