In Conversation with

Jay A. Gupta

Billy Lezra

There are twelve of us sitting around a wood table shaped like a horseshoe. Professor Gupta projects a black and white photograph onto the whiteboard and asks: “Is this image true or false?” Later we learn that an image can never be true or false. There is only a true or false caption.

It’s late August, 2016. I’m a twenty-three-year-old college junior. “If you don’t study with Jay Gupta while you’re here you’re wasting your time,” said one of my advisors. So I sign up for his 11:00 AM study of aesthetics—the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature and appreciation of art and beauty.

Professor Gupta is the only person who gives me a C on a paper. When I go to his office hours to ask why, he explains: “You told me where you arrived but you didn’t show me how you got there.” So, four years later, it is an honor and a joy to gather a few questions from three of Professor Gupta’s former students and learn how he got here.

(From Cass Lintz) Do you remember experiencing a specific piece of art that made you interested in the philosophy of aesthetics?

I would say that it was really a particular experience with artists in conversation about their art and not any particular artwork that has made Aesthetics one of my favorite courses to teach. I was first called upon to teach Aesthetics at the Lebanese American University, where I taught before coming to Mills. I had always considered it to be the least well defined of the “philosophy of –” subjects, trying to pack too many disparate practices and mediums into one course (painting, music, literature, etc.– and then from what perspective? Appreciation? The creative process? Etc.) But then I had a watershed moment teaching Aesthetics in 2010 to Mills MFA students, who appeared to be annoyed with it in the same way I was – too abstract, too distant from their practice. Mary Ann Milford, who was, if I recall correctly, the Chair of the Studio Arts Department at the time, advised me: “Jay, they’re artists. What they really want you to do is to look at their work.”

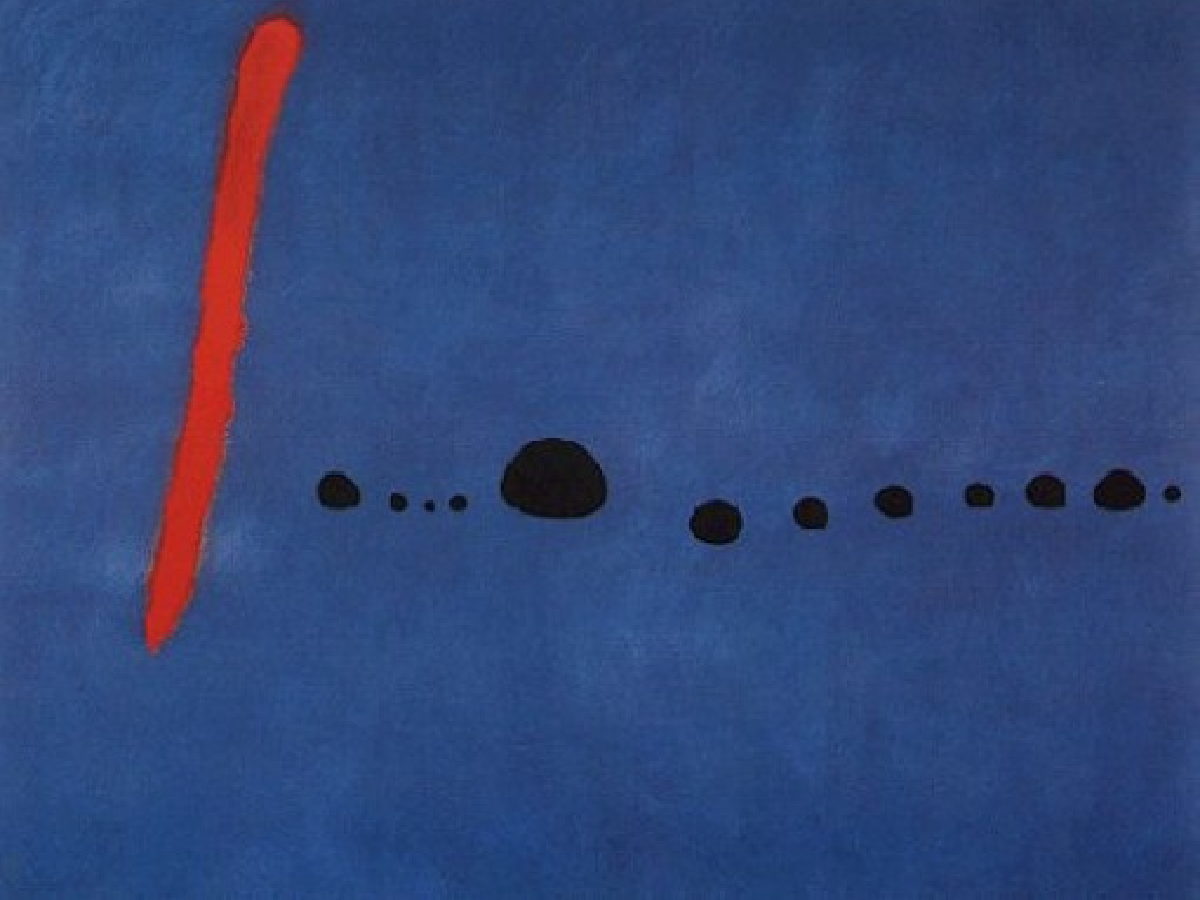

So I did. I did studio visits, and I commented on their works in progress, and I made sure to use the concepts we were discussing in the course. And it was a big hit, the very model of “dis-alienation”. They turned me on to the Artist’s Lecture that year given by Robert Irwin, who was really inspiring. In the course of a brilliantly rambling and engaging talk, he said something to the effect that artists today are what philosophers used to be: daring, experimental, willing to take risks, willing to think things out in the process of doing them. And he memorably used the example of a simple painted line on canvas (which I think he rehearsed in front of the audience), the sort of modernist painting that is typically the object of derision to the untutored viewer. He took the audience through the process of drawing the line, and I can’t quite recall the specifics of what he said, but the upshot was that the line is a record of questions, and of a trial and error process in attempting to answer them. And a good work of art captures and embeds that process. So the answer to your question is that it was a particular experience with artists talking about their art and not a particular artwork that has made Aesthetics one of my favorite courses to teach.

In your opinion, what is “good” art?

I think I’m sort of with Dewey on this one: I think good (great?) art in some way can substitute for experience, or create experience. It provokes a flood of thought and feeling. It in some way makes thought sensuous. It teaches us to see and hear. You can learn something from it, about yourself, about the world, about your relationships. Weber spoke of the “disenchantment of the world”; well, good modern art in particular has the power of re-enchantment: Is that bed hanging from the wall really just a bed? There is a characteristic process of de-familiarization with the world of the ordinary that can serve to illuminate the blindly pragmatic and instrumentalized routines that constitute everyday life. In this respect, good art encourages us to take seriously the idea that some things, activities, and relationships have intrinsic meaning and are inherently worthwhile. I believe that much of the way we necessarily live our lives encourages a kind of amnesia about this basic fact: that unless some things, activities, and relationships are intrinsically meaningful and worthwhile, nothing else we do would have meaning or value. Art counters this tendency with promoting attention to what has inherent meaning and worth; it has the capacity to re-enchant a disenchanted world.

What is the function of art within society?

I think I would just add to what I said above: there are certain tendencies in society, with its tangle of often competing pragmatic demands and commitments, to forget about even just the idea that some things, activities, and relationships are inherently good and meaningful. This is something we need to be reminded of, even educated about. For over a hundred years there has been a pressure on artists to “be political”. This trend began with the Marxist reaction to l’art pour l’art: art demonstrates its social value by critiquing and challenging the status quo and the various forms of economic and social alienation. And there is, of course, plenty to challenge: unjust exclusions based on race and gender, social and wealth inequality, political oppression. Art should of course challenge these things, and it should not encourage a kind of false sense of “dis-alienation” amongst an educated (and wealthy) elite. However, I think it is arguably a social issue of the first rank when, for example, I teach Aristotle, and undergraduates have a hard time grasping the very idea of “intrinsic worth”. This is an idea that is important to understanding Ancient philosophy in general; it is the idea of something that does not derive its worth from something else. Money, for example, is paradigmatic of something that is valuable because of something else. Money is valuable because of the things it can get you. It is also a good example of something that can falsely substitute for things that do have intrinsic worth: certain kinds of activities and relationships (I’ll leave it open to the reader to decide what these are). And that is arguably a mistake that many, many people make, indeed in making some of the most important life decisions about careers, partners, and so forth.

What is the best piece of advice you have ever received?

When I hear the word ‘advice’, I always think of that Oscar Wilde quote, “The only thing to do with good advice is pass it on. It is never any use to oneself.” But now thinking about it more seriously, it occurs to me that my undergraduate mentor, Kenley Dove, gave me advice that arguably had far-reaching consequences. When I asked him whether I should select a graduate school based on whether a particular philosopher was there (in this case, Stanley Rosen), he said, “That would be stupid.” This remark wasn’t really about Stanley Rosen, with whom Kenley was friends, but more generally about the process of selecting a graduate school. He followed up with, “When you get to graduate school, you’re largely going to have to go by your own lights.” And I think this latter remark, taken as a piece of advice, has had far-reaching consequences on whom I chose as my advisor, what I chose to write about in my dissertation, how I remained motivated, and how I maintained a sense of intellectual identity over the many years it took to complete the Ph.D. program and move on professionally.

(From Molly Stuart) What are your thoughts thus far on attempting to educate during a pandemic?

It’s tough. It’s a lot to get used to. I think I really rely quite a bit on the physicality of the classroom, on eye contact, on reading the room. It sort of feels like I’m talking into a black hole when I talk into a computer. And I think it encourages a certain laziness if you don’t have to read the room, that is, you give up on being directly responsive to those physical cues you’re getting from the class. It is difficult in general to get full participation from a class, but distance learning magnifies the problem. There is no substitute for a physical classroom where everyone can be together, joined in the common effort of discussing and learning the material.

In your opinion, what is a “good” teacher?

I’m inclined to start by referring to my experience as a student rather than as a teacher, which involves two rather different perspectives. The very best teachers in my life have had an effect on how I perceive and think about the world, which to me has been attached to my growth as a person. It is maybe not an accident that they were mostly philosophers, and ones whom I encountered as an undergraduate. These teachers uniquely inspired me, and also left me with enduring dispositions to think in certain ways about the world and my place in it. This set the bar very high for me as a graduate student just starting to learn the craft of teaching. It was in many ways unproductive. For I felt the burden of trying to channel the powerful effect these teachers had on me, at the expense of attempting to practice techniques that would reach all paying customers, as it were. And I’ve gradually tried to get better at the latter throughout my career. The temptation in a classroom is to have intensive conversations with the “alphas”, so to speak, which of course tends to exclude everyone else, some of whom might have a real interest in learning the subject. So I’ve tried to become more egalitarian in my methods, and I try to reach as many students as possible.

Where do you go to find inspiration?

I can’t say I go anywhere in particular. I would say that San Francisco is a treasure trove of inspiring, extraordinarily “vibey” places. I love Ocean Beach and the adjacent Lands End area. I love the California coast (who doesn’t?). I love the Headlands (the Headlands Center for the Arts seems to me to be an ideal place to do an Artist Residency); I love Inverness and Point Reyes. And Big Sur seems to me to contain mysterious multitudes. As far as the rest of Earth goes, I have found Berlin, Rome, and Florence to be particularly inspiring, and of course my hometown, New York City. (I’ll give props to Upstate too: the Adirondacks is a deep, mysterious, and wonderful place to be.)

Where do you go to find hope?

A new one? : ) I suppose this is a rather traditional answer, but I feel hopeful in churches. I’m not particularly religious, nor have I ever practiced religion, but there’s nothing like being inside a beautifully built church. And despite my general agnosticism, during the school year I bring my kids to the religious education (“Sunday School”) offered at the First Unitarian Universalist Society in San Francisco (both a hopeful and inspiring setting). My late wife Aileen and I had discussed this as a place for the kids to receive religious instruction, which was one of her final wishes. Interestingly, though, she was even less religious than me. When you get down to it, there is something deeply impressive about the reason churches exist: for “God”, yes, but (and I guess this outs me as a Hegelian) I believe that they fundamentally exist to offer a space to celebrate, honor, interrogate, feel, and encounter the human spirit. This reminds me of one of Hegel’s remarks: Art is produced by the spirit, for the spirit. And interestingly, Hegel groups art, religion, and philosophy together as marking different aspects of one “absolute” domain of spiritual enterprise.

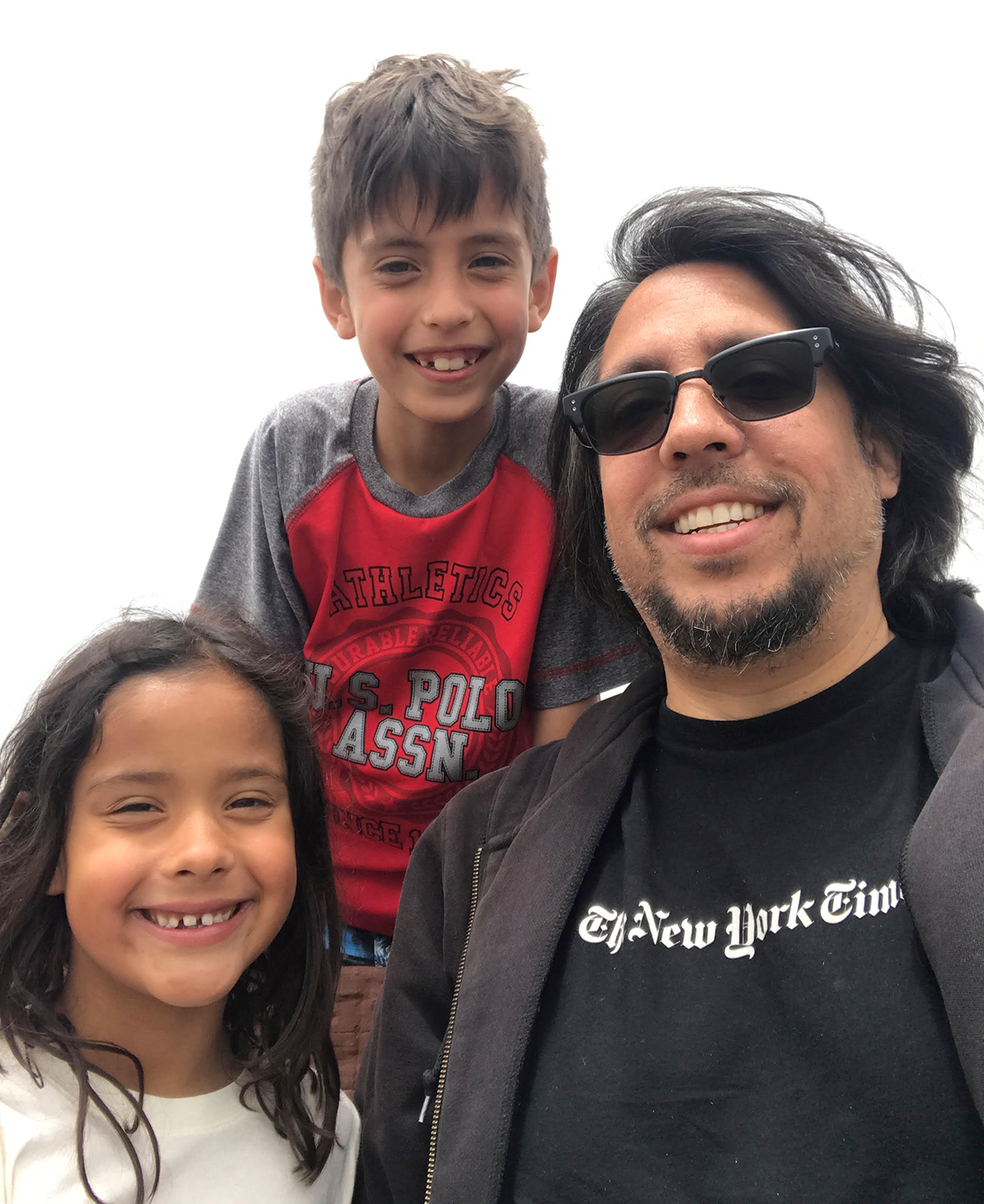

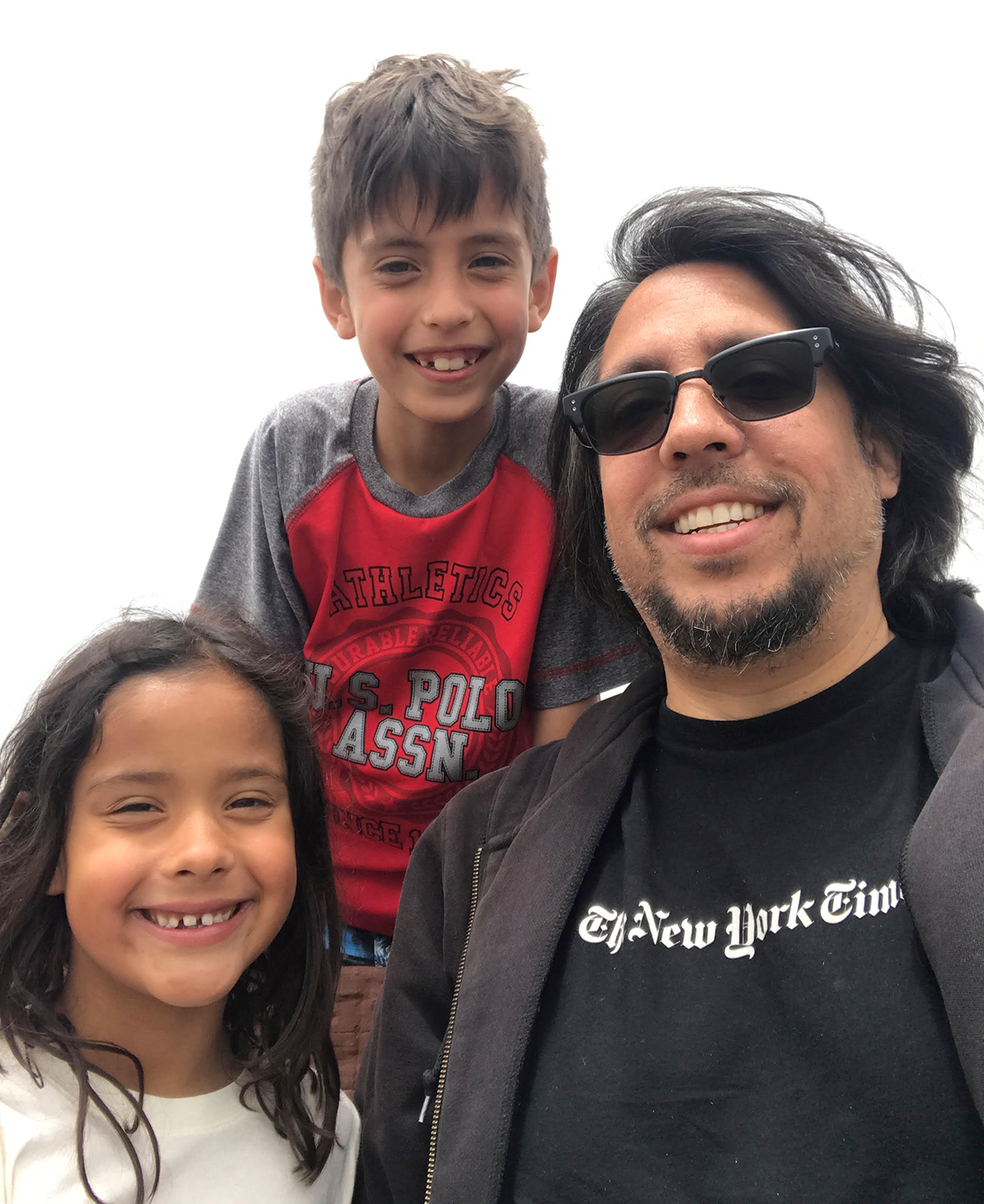

(From Lauren K. Dougherty) How has having children influenced your creativity and the way you approach your work?

I have eight-year old twins, a girl (Kenley) and a boy (Anakin), and they have been an incalculable boon on my life. They’re both very creative people, and in a way they model creativity through their characteristic ways of interacting. Above, I spoke of art as having a “de-familiarizing” effect; I think kids in many ways have a similar effect. Interacting with them is like being involved in some sort of profound, joyous, open-ended experiment. I don’t want to downplay the everyday challenges of parenting; they’re definitely there (often work either just doesn’t get done, or there are serious time constraints). But I don’t think this particular aspect of having children gets articulated very often, so it’s a very good question. Having kids is an adventure in learning, feeling, and experiencing.

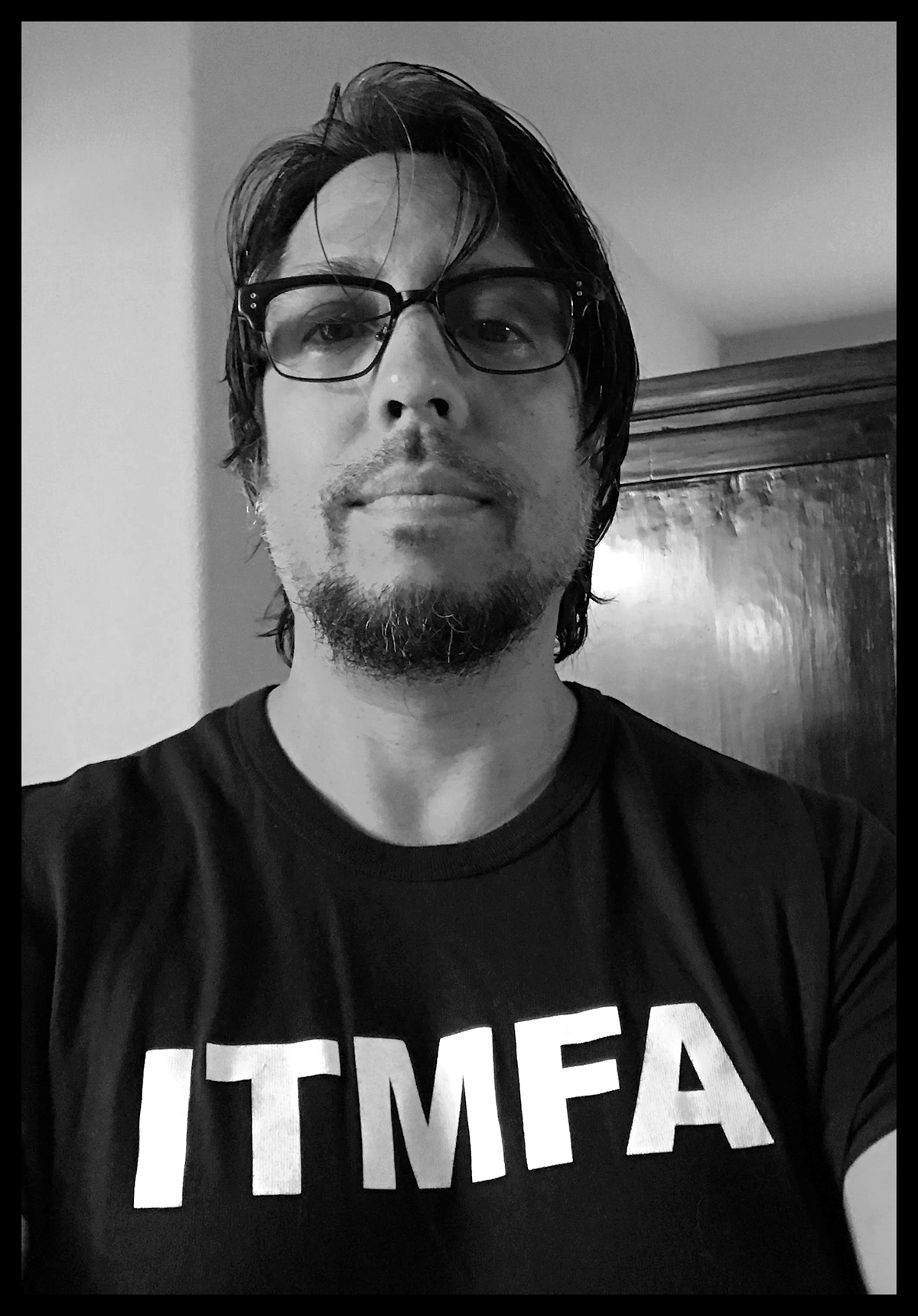

Jay A. Gupta is an Associate Professor of Philosophy and the Lorry I. Lokey Endowed Chair in Ethics at Mills College in Oakland, CA. He has a background in 19th Century philosophy, particularly Hegel, and writes on a variety of topics, particularly on those where theories of ethics, politics, aesthetics, and consciousness intersect. He has been a longtime editorial associate of the journal of critical theory, Telos, and is presently its Review Editor.

In Conversation with

Jay A. Gupta

Billy Lezra

August 21st, 2016. Oakland, California. I’m a twenty-three-year-old college junior on my way to my first class of the year. “If you don’t study with Jay Gupta while you’re here you’re wasting your time,” said one of my advisors. So I signed up for his 11:00 AM study of aesthetics—the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature and appreciation of art and beauty.

There are twelve of us sitting around a wood table shaped like a horseshoe. Professor Gupta projects a black and white photograph onto the whiteboard and asks: “Is this image true or false?” Later we learn that an image can never be true or false. There is only a true or false caption.

Professor Gupta was the only person who gave me a C on a paper. When I went to his office hours to ask why, he explained: “You told me where you arrived but you didn’t show me how you got there.” This feedback changed the way I approached the act of thinking about and creating art.

(From Cass Lintz) Do you remember experiencing a specific piece of art that made you interested in the philosophy of aesthetics?

I would say that it was really a particular experience with artists in conversation about their art and not any particular artwork that has made Aesthetics one of my favorite courses to teach. I was first called upon to teach Aesthetics at the Lebanese American University, where I taught before coming to Mills. I had always considered it to be the least well defined of the “philosophy of –” subjects, trying to pack too many disparate practices and mediums into one course (painting, music, literature, etc.– and then from what perspective? Appreciation? The creative process? Etc.) But then I had a watershed moment teaching Aesthetics in 2010 to Mills MFA students, who appeared to be annoyed with it in the same way I was – too abstract, too distant from their practice. Mary Ann Milford, who was, if I recall correctly, the Chair of the Studio Arts Department at the time, advised me: “Jay, they’re artists. What they really want you to do is to look at their work.”

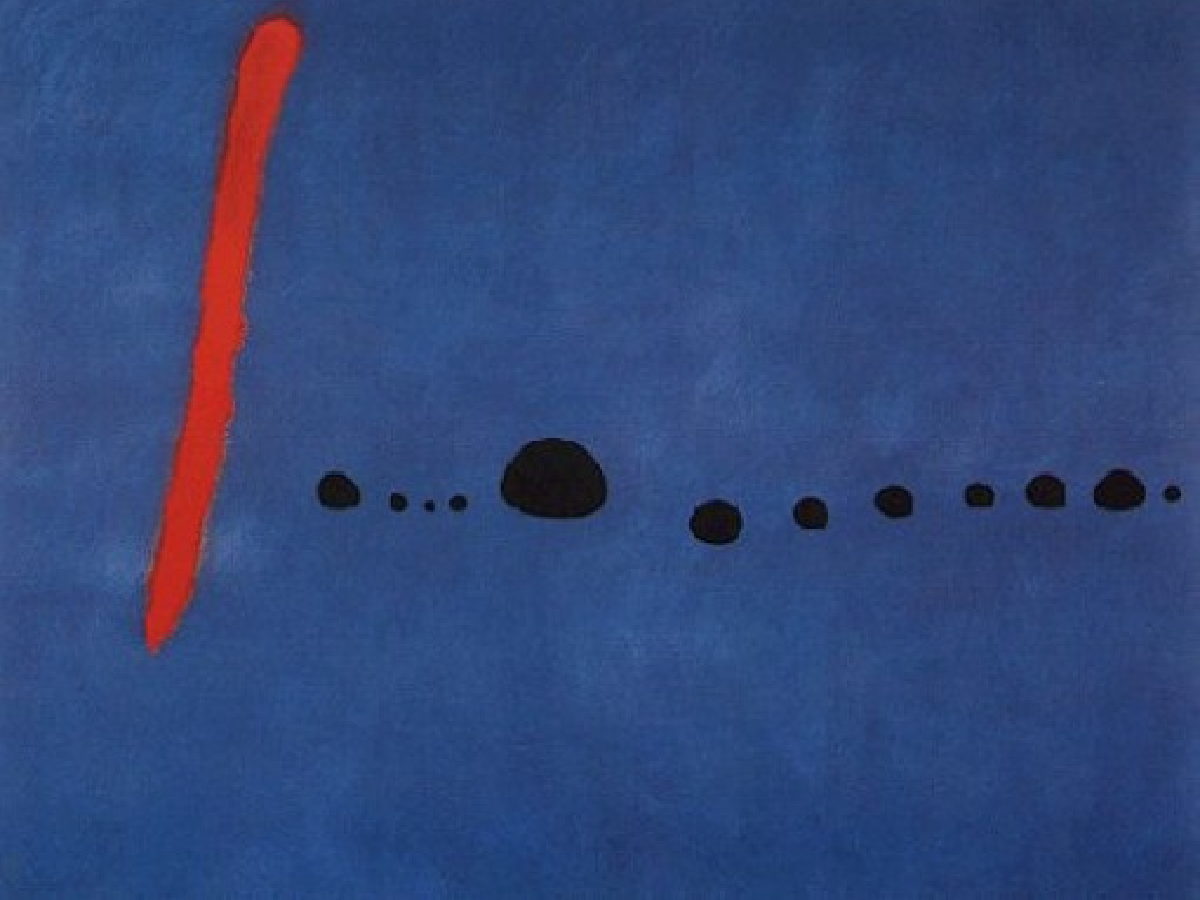

So I did. I did studio visits, and I commented on their works in progress, and I made sure to use the concepts we were discussing in the course. And it was a big hit, the very model of “dis-alienation”. They turned me on to the Artist’s Lecture that year given by Robert Irwin, who was really inspiring. In the course of a brilliantly rambling and engaging talk, he said something to the effect that artists today are what philosophers used to be: daring, experimental, willing to take risks, willing to think things out in the process of doing them. And he memorably used the example of a simple painted line on canvas (which I think he rehearsed in front of the audience), the sort of modernist painting that is typically the object of derision to the untutored viewer. He took the audience through the process of drawing the line, and I can’t quite recall the specifics of what he said, but the upshot was that the line is a record of questions, and of a trial and error process in attempting to answer them. And a good work of art captures and embeds that process. So the answer to your question is that it was a particular experience with artists talking about their art and not a particular artwork that has made Aesthetics one of my favorite courses to teach.

In your opinion, what is “good” art?

I think I’m sort of with Dewey on this one: I think good (great?) art in some way can substitute for experience, or create experience. It provokes a flood of thought and feeling. It in some way makes thought sensuous. It teaches us to see and hear. You can learn something from it, about yourself, about the world, about your relationships. Weber spoke of the “disenchantment of the world”; well, good modern art in particular has the power of re-enchantment: Is that bed hanging from the wall really just a bed? There is a characteristic process of de-familiarization with the world of the ordinary that can serve to illuminate the blindly pragmatic and instrumentalized routines that constitute everyday life. In this respect, good art encourages us to take seriously the idea that some things, activities, and relationships have intrinsic meaning and are inherently worthwhile. I believe that much of the way we necessarily live our lives encourages a kind of amnesia about this basic fact: that unless some things, activities, and relationships are intrinsically meaningful and worthwhile, nothing else we do would have meaning or value. Art counters this tendency with promoting attention to what has inherent meaning and worth; it has the capacity to re-enchant a disenchanted world.

What is the function of art within society?

I think I would just add to what I said above: there are certain tendencies in society, with its tangle of often competing pragmatic demands and commitments, to forget about even just the idea that some things, activities, and relationships are inherently good and meaningful. This is something we need to be reminded of, even educated about. For over a hundred years there has been a pressure on artists to “be political”. This trend began with the Marxist reaction to l’art pour l’art: art demonstrates its social value by critiquing and challenging the status quo and the various forms of economic and social alienation. And there is, of course, plenty to challenge: unjust exclusions based on race and gender, social and wealth inequality, political oppression. Art should of course challenge these things, and it should not encourage a kind of false sense of “dis-alienation” amongst an educated (and wealthy) elite. However, I think it is arguably a social issue of the first rank when, for example, I teach Aristotle, and undergraduates have a hard time grasping the very idea of “intrinsic worth”. This is an idea that is important to understanding Ancient philosophy in general; it is the idea of something that does not derive its worth from something else. Money, for example, is paradigmatic of something that is valuable because of something else. Money is valuable because of the things it can get you. It is also a good example of something that can falsely substitute for things that do have intrinsic worth: certain kinds of activities and relationships (I’ll leave it open to the reader to decide what these are). And that is arguably a mistake that many, many people make, indeed in making some of the most important life decisions about careers, partners, and so forth.

What is the best piece of advice you have ever received?

When I hear the word ‘advice’, I always think of that Oscar Wilde quote, “The only thing to do with good advice is pass it on. It is never any use to oneself.” But now thinking about it more seriously, it occurs to me that my undergraduate mentor, Kenley Dove, gave me advice that arguably had far-reaching consequences. When I asked him whether I should select a graduate school based on whether a particular philosopher was there (in this case, Stanley Rosen), he said, “That would be stupid.” This remark wasn’t really about Stanley Rosen, with whom Kenley was friends, but more generally about the process of selecting a graduate school. He followed up with, “When you get to graduate school, you’re largely going to have to go by your own lights.” And I think this latter remark, taken as a piece of advice, has had far-reaching consequences on whom I chose as my advisor, what I chose to write about in my dissertation, how I remained motivated, and how I maintained a sense of intellectual identity over the many years it took to complete the Ph.D. program and move on professionally.

(From Molly Stuart) What are your thoughts thus far on attempting to educate during a pandemic?

It’s tough. It’s a lot to get used to. I think I really rely quite a bit on the physicality of the classroom, on eye contact, on reading the room. It sort of feels like I’m talking into a black hole when I talk into a computer. And I think it encourages a certain laziness if you don’t have to read the room, that is, you give up on being directly responsive to those physical cues you’re getting from the class. It is difficult in general to get full participation from a class, but distance learning magnifies the problem. There is no substitute for a physical classroom where everyone can be together, joined in the common effort of discussing and learning the material.

In your opinion, what is a “good” teacher?

I’m inclined to start by referring to my experience as a student rather than as a teacher, which involves two rather different perspectives. The very best teachers in my life have had an effect on how I perceive and think about the world, which to me has been attached to my growth as a person. It is maybe not an accident that they were mostly philosophers, and ones whom I encountered as an undergraduate. These teachers uniquely inspired me, and also left me with enduring dispositions to think in certain ways about the world and my place in it. This set the bar very high for me as a graduate student just starting to learn the craft of teaching. It was in many ways unproductive. For I felt the burden of trying to channel the powerful effect these teachers had on me, at the expense of attempting to practice techniques that would reach all paying customers, as it were. And I’ve gradually tried to get better at the latter throughout my career. The temptation in a classroom is to have intensive conversations with the “alphas”, so to speak, which of course tends to exclude everyone else, some of whom might have a real interest in learning the subject. So I’ve tried to become more egalitarian in my methods, and I try to reach as many students as possible.

Where do you go to find inspiration?

I can’t say I go anywhere in particular. I would say that San Francisco is a treasure trove of inspiring, extraordinarily “vibey” places. I love Ocean Beach and the adjacent Lands End area. I love the California coast (who doesn’t?). I love the Headlands (the Headlands Center for the Arts seems to me to be an ideal place to do an Artist Residency); I love Inverness and Point Reyes. And Big Sur seems to me to contain mysterious multitudes. As far as the rest of Earth goes, I have found Berlin, Rome, and Florence to be particularly inspiring, and of course my hometown, New York City. (I’ll give props to Upstate too: the Adirondacks is a deep, mysterious, and wonderful place to be.)

Where do you go to find hope?

A new one? : ) I suppose this is a rather traditional answer, but I feel hopeful in churches. I’m not particularly religious, nor have I ever practiced religion, but there’s nothing like being inside a beautifully built church. And despite my general agnosticism, during the school year I bring my kids to the religious education (“Sunday School”) offered at the First Unitarian Universalist Society in San Francisco (both a hopeful and inspiring setting). My late wife Aileen and I had discussed this as a place for the kids to receive religious instruction, which was one of her final wishes. Interestingly, though, she was even less religious than me. When you get down to it, there is something deeply impressive about the reason churches exist: for “God”, yes, but (and I guess this outs me as a Hegelian) I believe that they fundamentally exist to offer a space to celebrate, honor, interrogate, feel, and encounter the human spirit. This reminds me of one of Hegel’s remarks: Art is produced by the spirit, for the spirit. And interestingly, Hegel groups art, religion, and philosophy together as marking different aspects of one “absolute” domain of spiritual enterprise.

(From Lauren K. Dougherty) How has having children influenced your creativity and the way you approach your work?

I have eight-year old twins, a girl (Kenley) and a boy (Anakin), and they have been an incalculable boon on my life. They’re both very creative people, and in a way they model creativity through their characteristic ways of interacting. Above, I spoke of art as having a “de-familiarizing” effect; I think kids in many ways have a similar effect. Interacting with them is like being involved in some sort of profound, joyous, open-ended experiment. I don’t want to downplay the everyday challenges of parenting; they’re definitely there (often work either just doesn’t get done, or there are serious time constraints). But I don’t think this particular aspect of having children gets articulated very often, so it’s a very good question. Having kids is an adventure in learning, feeling, and experiencing.

Jay A. Gupta is an Associate Professor of Philosophy, the Lorry I. Lokey Endowed Chair in Ethics, and the Head of the Global Humanities and Critical Thought Program at Mills College in Oakland, CA. He has a background in 19th Century philosophy, particularly Hegel, and writes on a variety of topics, particularly on those where theories of ethics, politics, aesthetics, and consciousness intersect. He has been a longtime editorial associate of the journal of critical theory, Telos, and is presently its Review Editor.