A Bookmark for Unconditional Love

In Conversation with Jeffrey Marsh

Billy Lezra

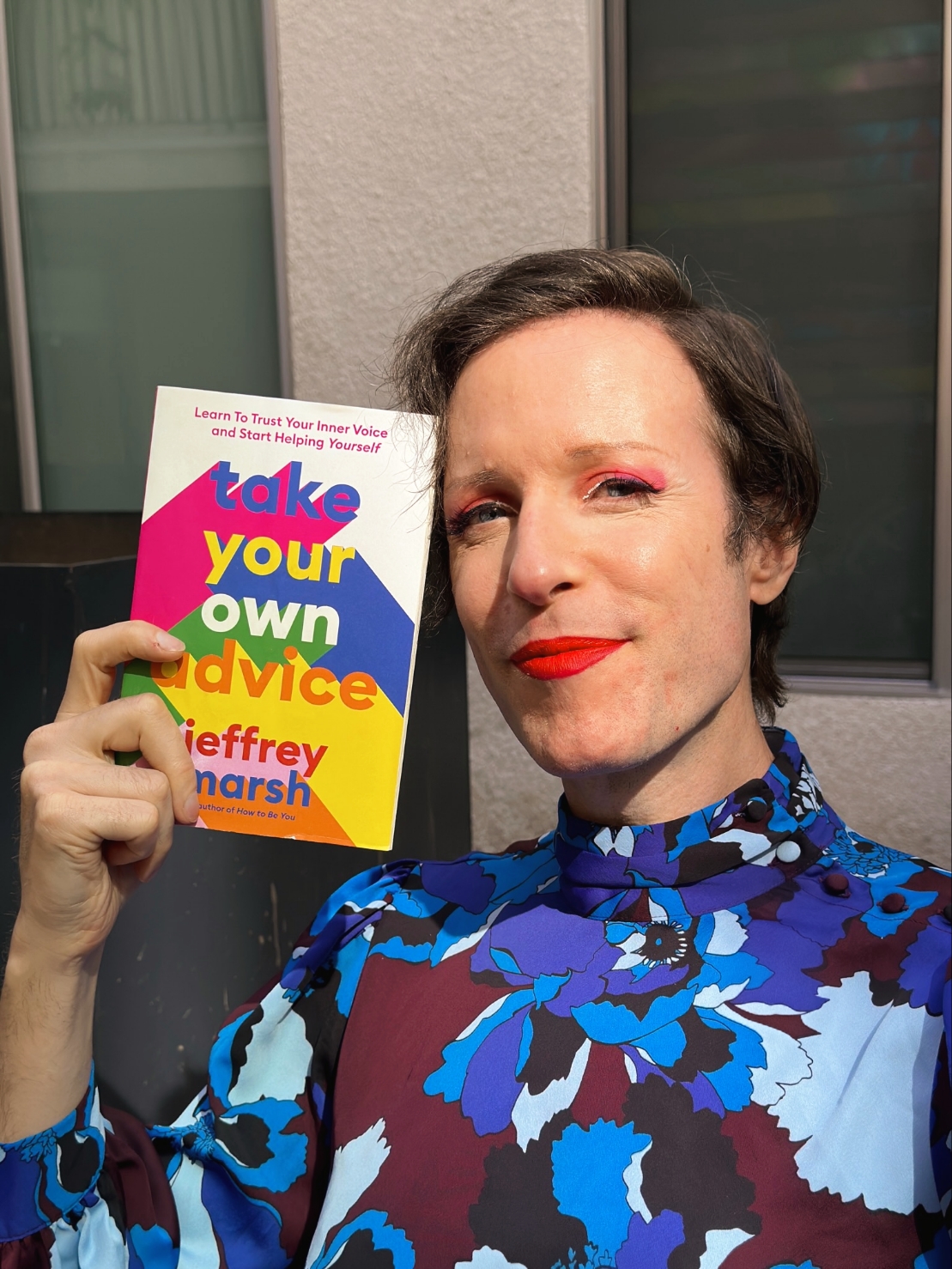

photo credit: Jeff E Photo

Jeffrey Marsh is a bestselling author, viral TikTok and Instagram star, nonbinary activist, and LGBTQ keynote speaker. Jeffrey is the first nonbinary author to sign a book deal with any “Big 5” publisher worldwide, for Penguin Random House. Jeffrey’s #1 bestseller, How to Be You, topped Oprah’s Gratitude Meter and was named Excellent Book of the Year by TED-Ed. Jeffrey’s second book, Take Your Own Advice, was a #1 Amazon Best Seller, outselling all Self-Esteem books upon its release. Jeffrey has spoken at the U.N. and for global brands like Target and BNP, and has reported on LGBTQ topics for Good Morning America, The New York Times, Variety, TIME, and the BBC. In addition, Jeffrey was an LGBTQ consultant for Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign and has consulted for New York University, GLAAD, MTV, Condé Nast’s Them, and Teen Vogue.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

One of the most beautiful ideas I read in Take Your Own Advice was this notion of waiting for clarity to arrive, in order to make a decision. How did it become clear to you that it was time to write this book?

I knew people were suffering, as they still are, due to political unrest and the pandemic and everything else. Feeling isolated and lonely has caused many people to reassess why and how they’d like to be living their lives. During the pandemic, circa 2020, I went no-contact with my family, which was a huge step toward giving up on the guilt associated with fully telling my own story. And writing this book was like a big, broad invitation to share more about what had happened to me, and also more of the wisdom I learned through living at the monastery.

What was your journey toward Buddhism and the monastery?

It was sheer desperation: utter, complete desperation. As a young person, I heard a lot of negative messages growing up, and I took the outside voices and made them inside voices. That kind of self-talk was extremely detrimental, and I almost didn’t make it without doing something very desperate, which was to go live with a bunch of monks for a while. I’ve been studying Zen for almost 25 years now. I have this clear sense that spiritual practice happens everywhere. And there are certain supports when you’re living at the monastery, but there are also supports out here in what we might call “the outside world.” But the mission doesn’t change, and the orientation to living doesn’t change.

How has the decision to go no-contact with your parents affected your life?

It was a master class in guilt and in learning to get over and give up on guilt. When people assume that guilt has utility, I think it’s because what they’re really pointing to is that compassion has utility. So, in other words, if I hurt a friend’s feelings, if I can open myself to the true compassion of understanding how they’ve been hurt, this will change my behavior. Feeling guilty and bad doesn’t change behavior and isn’t worth it.

What you’re saying about compassion is making me think about the letters to the younger Jeffreys in your book. What was it like to write those letters to yourselves?

Cathartic. It was exciting. It was nice. It was wonderful. It was heart-opening, and it was healing. I decided that in addition to talking about 6-year-old Jeffrey, 13-year-old Jeffrey, and 18-year-old Jeffrey, I could thank them: I could write to them and tell them how I feel. And it wasn’t clear whether I would include those letters in the book, but my publisher liked that idea. So kudos to Penguin for suggesting that they go in because it’s been healing for a lot of people. I get emails about those letters a lot.

What was your writing process like?

I wanted this book to flow like a conversation with a friend. Someone told me, “It feels like I’m on a river and you’re just guiding me along.” So the real genesis of the book was to make recordings as if I was talking to a friend, and then taking those recordings, transcribing them, and working with them to create the text that eventually made its way into the book. Hopefully, what has been kept in that process is the real familiar feeling and the kind, inviting tone of the book. And that’s because, in a way, that’s my signature: people are drawn to my work because of that friendly feeling and knowing that they’re included and that we’re connecting. So I had to approach the book in a way that would preserve that.

photo credit: Jeff E Photo

There’s a section in your book where you delve into what it means to be an authority. And I found myself thinking about the similarity between the words author, authority, and authenticity. What has been your journey into stepping into the authority of your authenticity?

That is the only way we can do it. It is possible, obviously, to be an authority on a subject–to be a subject matter expert. That happens all the time. But there is no one else that is an authority on your experience, on your worldview, on the things that have shaped what you care about. So to me, one thing that’s essential is accepting that you are an authority. You are an author of this human being’s outlook, and you can make conscious choices to express that in ways that help bring people together.

How do you accept that you are an authority?

Well, I talk about this a little bit in the book, but I despise the phrase “fake it till you make it,” because ultimately it’s not fake. So it’s more like: “Real it until you make it.” It’s more like: “Express what is real and true, even if you have internal programming fighting against you.” And eventually you will wear down that programming. And the good news is you will live constantly in the truth.

In a TED Talk you gave, you said that: “The thing that you were taught is most wrong with you is your greatest asset as an activist.” How and when did you begin to discover this for yourself?

I began to discover this because being me is fun, to be honest. I was famous on Vine, this would be a decade ago, and those videos were six and a half seconds long. And what six and a half seconds allowed me to do was have just enough time to say, “There is nothing wrong with you” to the camera, which is a complete distillation of who I am and what I’m trying to do here. And then I really began to devote my entire life, my work, and my career, to that. Of course, I had the spiritual foundation of being a Buddhist. Making Vines was the real-world version of this. And I’ll tell you, back on Vine, it was a little Wild Westy. You couldn’t block people, you couldn’t delete somebody’s comments, and you couldn’t filter words. It was an experience, shall we say. And I thought many a time: “Do I want other LGBTQ people, or just other people in general, to see someone like me constantly getting hate, day after day after day?” And then I realized: that is also part of the mission. That’s also part of the point: that I would post one day, get hate, and then post the next day, and then post again, and then post again–this was part of the process. In short, what I do is not for them or about them.

I watched the interview you did with Newsmax, and I really admired your grace when confronted with disrespectful questions. How do you protect your spirit in hostile spaces?

Yeah, Newsmax was hostile. This was years ago, pre-pandemic, my first book had just come out, and I thought: “Well, if my mission is to reach people, then I might reach somebody.” And that seemed reasonable at the time, but Newsmax was not a fun environment. They were anti-Jeffrey and anti-LGBTQ people. And the way I protected myself was to say nice things to myself. So we’re on set, and I’m sitting there by myself. There are sound people, camera people, but it’s basically just me and the host. We are about to do the segment and I’m saying to myself: “Thank you, Jeffrey. This is so important. I’m so glad you’re here. I love you. Let’s do something fun afterward.” This is the way that I talk to myself. And then when the red light goes on, on top of the camera, and it’s time to go, I’m already in that space. And even if the interviewer wants to pull me from that space, that’s where the real work begins–practicing not allowing that to happen.

It reminds me of what you wrote, about how it is impossible to nail Jell-O to a wall.

Yeah. A fight takes two people, and my teacher at the monastery would liken it to asking someone to nail Jell-O to the wall. Someone looking for a fight wants resistance so that their nail has someplace to be and they can bang away with their hammer. But if it’s like Jell-O and you just relax into what you’re there to do, which in my case was love and kindness, then they’re not meeting resistance. And there’s very little they can do with that.

In an interview with PBS, you invited the interviewer to describe you in a word, and he said “light.” And then you said: “Well, you just described yourself.” I was curious about how you came to this understanding–that you are a mirror.

I realized quite a long time ago that my mission in life is to draw out what needs to be healed in people. Sometimes that is a great thing if they are in a place where that is what they want. But sometimes it gets ugly: I draw out their bigotry or whatever they need to get over in order to have peace in their lives. And they rebel, which is understandable. But my mission doesn’t change. What I’m here to do doesn’t change. And what I hope to be is a bookmark for unconditional love and acceptance until people realize that unconditional love is actually within them and has been the whole time. I’m always pointing people toward the realization that whatever they see in me is because they have it already.

Was understanding that you are a mirror a gradual realization?

I first learned about the principle of projection at the monastery, twenty-ish years ago, and it’s also a Western therapy concept. But it gets close to the Buddhist idea of oneness: that there’s nothing in me that’s not in you, that we’re connected in that way. It’s still a process of it settling in and becoming a daily practice, to remember that and to celebrate it.

Would you speak about the role of humor and laughter in your work?

I find humor essential, and I’m not the only one. Often, in all kinds of world religions, there is a role for a joker, for someone who turns reality on its head. And not for nothing, this is a role that trans people fulfill in society. Often people want to make it extremely serious, and I disagree. We should show up, we shouldn’t shirk our duties, but we absolutely need to have fun while we’re doing it. It doesn’t make sense to me otherwise.

When was the first time you felt like you belonged and that you were loved exactly as you are?

Actually, when I was a kid, I would dance and twirl around in our barn and pretend to be Julie Andrews. I felt like I created the loving family I always wanted, in this imaginary plane, because I was pretending to be Julie Andrews, but with an audience who loved me–with a family sitting around who was encouraging me and loving me. So it was sort of like a coping mechanism, but it also strikes me as being very LGBTQ. So many of us patch together the self-esteem, the kindness, the chosen family, the support system we need. We just gather dribs and drabs and little pieces from here and there and craft a full, beautiful quilt of a life from the ground up. Which actually sounds like a burden, but it is a blessing. So many people think that they have a support system or assume that they’re doing amazing because they happen to fit what society wants in one way or another. But so much of being an LGBTQ person is being an outsider. And I felt like an outsider even when I was a kid. But the benefit of being an outsider is that you know the system is fake.

So this sense of belonging and being loved was self-generated and had less to do with other people saying that you belonged?

I think it’s kind of both. Let’s be really ultra-clear: you can’t have transformations without other people. This is something the Buddha directly talked about. One of the three jewels of practice is practicing with a religious group, with other people, because you need those mirrors from others. And the hermit lifestyle is fine for some religious folks, but usually, when you have a group of people around, you get inspired, you feel connected, you feel that sense of belonging, and you grow. And that must be paired, in a nonbinary way, with work on the inside and choosing to grow yourself.

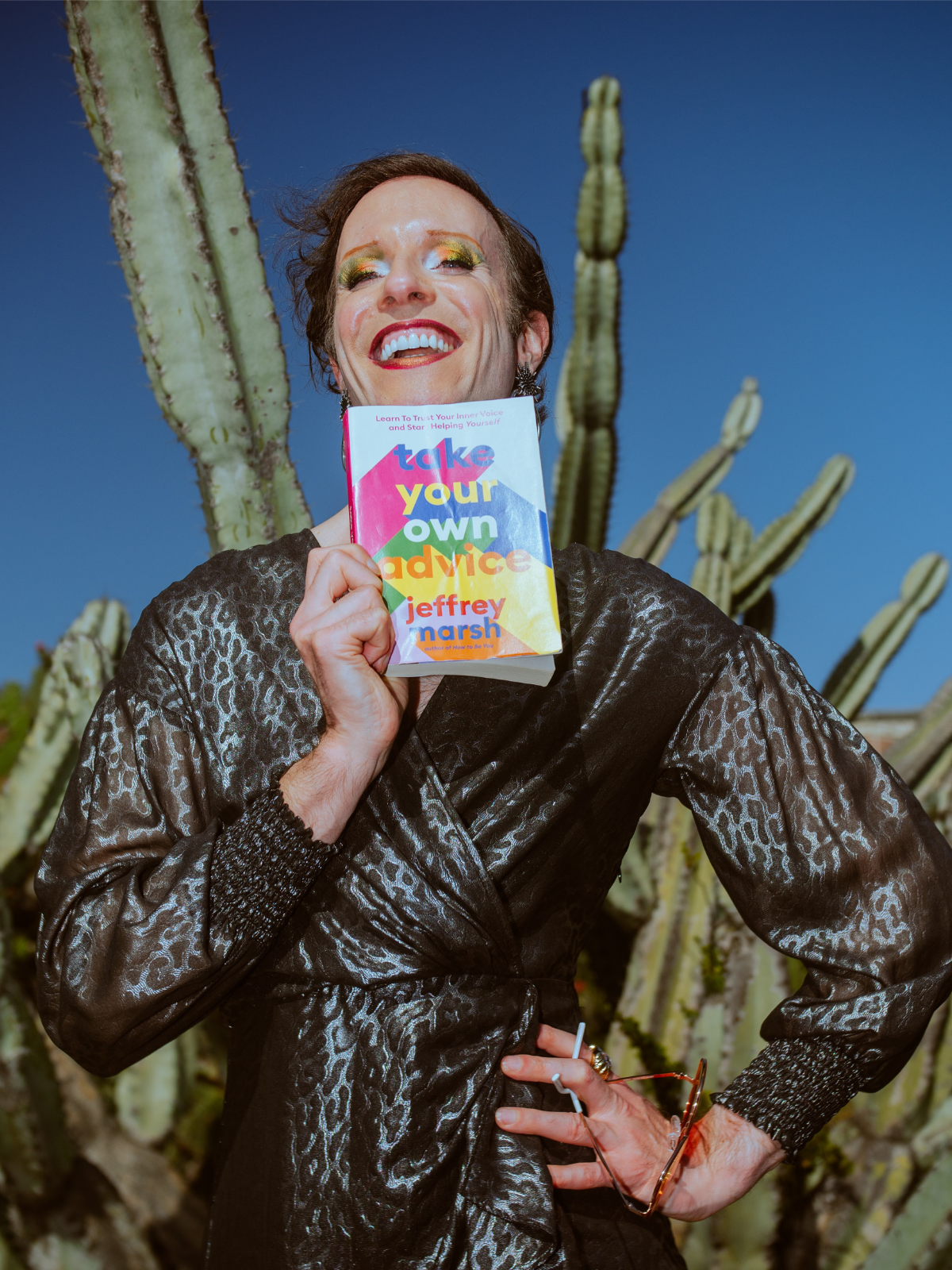

photo credit: Tomoki Kawa

I would like to ask you about anger. You write: “At its best, anger is a call to fairness and a hand stretched out in your direction, an invitation to honor how much you care.” How do you distinguish between generative anger and destructive anger?

Yes–what we might call righteous anger versus run-of-the-mill hate. To me, I think they’re one and the same. I’m going to give you a very non-binary answer: constructive and destructive anger both spring out of a sense of injustice. I would imagine that someone hateful hates me because there is some sense that my freedom is not available to them, which is an injustice: that I’m getting attention, that I deeply love myself, and that they’re not allowed to. And that sense of injustice creates a lot of anger, just from what I’ve observed. But anger can be a source for good because there’s a lot of injustice that ought to be overturned in this world. Anger is a friend. Anger is trying to tell you something. Jesus got very angry in the Bible, famously. And that story, as far as I understand it, is about injustice. So anger is human. Anger is a kindness. For so many of us who have been traumatized, the worst thing we can think of is inflicting trauma on other people. We tend to associate anger with one or both of our parents being very traumatic, violent, hateful, mean, being the chaos. And if you break anger away from those associations, it really is a story of injustice and sensations in your body. So anger can really be an invitation.

A word I’ve seen surface in your work is “nonviolence.” What does this idea mean to you?

I’m committed to nonviolence both internally and externally. And as we were discussing before, you almost can’t have one without the other. You can’t do activism to end the violence in the world without ending the internal violence as well.

What does it look like to be nonviolent with yourself?

Unconditional love. These phrases get thrown around and I’m guessing some people reading may be rolling their eyes. But what I mean is: even if something happens that doesn’t go well, even if you have feelings, you have trauma, you have things that are coming up…can you love yourself in every single situation? To me, judging yourself, hating yourself, those voices inside your head saying, “Why’d you do that?”, “They’re going to laugh at you,” “You’re so stupid”– that’s internal violence. And if you’re going to commit yourself to nonviolence and commit yourself to be nonviolent in every possible situation, that is a wide-open invitation for life to bring in things that may challenge you because you’ve committed to facing challenges.

What do you do when you start to hear that inner voice of violence?

You have several options. You can turn your attention to something else, which gets easier over time. So, you could treat the things I was saying on the set of Newsmax as a mantra: “Thank you. I love you. I’m so glad you’re here. Thank you. I love you. I’m so glad you’re here.” Just repeat, repeat, repeat. And as best as you can, turn your attention to that and away from the nasty voices in your head. The other thing to do, if that doesn’t seem available, is to start asking that voice questions. So, say something goes wrong at work. You send out an email and it’s the most important email, and it has a typo in it. And all of a sudden there are voices inside your head going: “Oh, how could you? You’re going to get fired. They hate you now. Now they know how awful you are.” All of that starts up. You do have the option–not a lot of people are aware–but you do have the option to turn around and say: “How do you know that? Who said that? Could you give me some proof of this?”

There seems to be a false idea: that I can speak to myself unkindly, but be kind to others, simultaneously.

A lot of people think the best way to be kind to others is to beat yourself into being kind. And this is where we get into what might sound like Dr. Phil territory, or Oprah in the nineties territory, with the idea of “put yourself first.” This is a solid spiritual principle, but it gets eye-rolly very fast. So to add some depth and context to that principle: if there is a choice point, choose yourself. And if there’s no choice point, then choose everyone, which includes yourself. And eventually, we learn that very often choosing ourselves is what’s kindest for all.

Another word that stood out to me in your book is “sparkle.” What does it mean for you to sparkle?

Well, people tell me I’m brave, and it’s the sparkly eyeshadow and the sparkly lip gloss, for sure. But there’s also a sparkle in having fun. People get the idea that I don’t take them very seriously, and it’s true, I don’t. I don’t take myself seriously, either. I take somebody’s true heart or essence or the core of their soul very seriously. But the trappings, the things we were taught, the things we’re all supposed to be trying to do to compensate for how awful we feel, and all those things that everybody wraps up their lives in, I don’t take that stuff very seriously at all. And I think it’s important to have fun and joke around as part of spiritual growth, And to me, the best way that you can take care of yourself is to embrace the unbearable lightness of being that’s sparkling. We’re not here for a long time.

How would you like to be remembered?

I would like to be remembered as a bookmark for the unconditional. After I am gone, I hope that anybody who knew me personally, or on the Internet, or through my life and work, will take from me an overwhelming sense that there is nothing wrong with them.

In the epilogue of your book, you write a letter to your 44-year-old self, in which you say: “I also know that you don’t talk much about the positive emails you get every day. You don’t talk about the emails that say, you saved my life.” What does it mean for little Jeffrey to know that big Jeffrey receives these emails?

It’s deeply important. So on one level, little Jeffrey doesn’t check the inbox and is just dancing around and having fun. But I think the importance of the impact and the fun I get to have is very much little Jeffrey. I was surprised and delighted that little Jeffrey taught me things, inspired me, helped me to have peace and to heal. And that there is a version of this inner child, this little Jeffrey, who is frozen in time and out of time when life was beautiful and innocent, lovely and colorful and wonderful. And little Jeffrey has stayed the bookmark into my adulthood to remind me that those things are there and worthwhile and fun and beautiful.

So little Jeffrey holds the sparkle, the laughter?

Yeah, to a large extent. And little Jeffrey has taught me, adult me, to sparkle more.

Take Your Own Advice is available for purchase here.

A Bookmark for Unconditional Love

In Conversation with Jeffrey Marsh

Billy Lezra

photo credit: Jeff E Photo

Jeffrey Marsh is a bestselling author, viral TikTok and Instagram star, nonbinary activist, and LGBTQ keynote speaker. Jeffrey is the first nonbinary author to sign a book deal with any “Big 5” publisher worldwide, for Penguin Random House. Jeffrey’s #1 bestseller, How to Be You, topped Oprah’s Gratitude Meter and was named Excellent Book of the Year by TED-Ed. Jeffrey’s second book, Take Your Own Advice, was a #1 Amazon Best Seller, outselling all Self-Esteem books upon its release. Jeffrey has spoken at the U.N. and for global brands like Target and BNP, and has reported on LGBTQ topics for Good Morning America, The New York Times, Variety, TIME, and the BBC. In addition, Jeffrey was an LGBTQ consultant for Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign and has consulted for New York University, GLAAD, MTV, Condé Nast’s Them, and Teen Vogue.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

One of the most beautiful ideas I read in Take Your Own Advice was this notion of waiting for clarity to arrive, in order to make a decision. How did it become clear to you that it was time to write this book?

I knew people were suffering, as they still are, due to political unrest and the pandemic and everything else. Feeling isolated and lonely has caused many people to reassess why and how they’d like to be living their lives. During the pandemic, circa 2020, I went no-contact with my family, which was a huge step toward giving up on the guilt associated with fully telling my own story. And writing this book was like a big, broad invitation to share more about what had happened to me, and also more of the wisdom I learned through living at the monastery.

What was your journey toward Buddhism and the monastery?

It was sheer desperation: utter, complete desperation. As a young person, I heard a lot of negative messages growing up, and I took the outside voices and made them inside voices. That kind of self-talk was extremely detrimental, and I almost didn’t make it without doing something very desperate, which was to go live with a bunch of monks for a while. I’ve been studying Zen for almost 25 years now. I have this clear sense that spiritual practice happens everywhere. And there are certain supports when you’re living at the monastery, but there are also supports out here in what we might call “the outside world.” But the mission doesn’t change, and the orientation to living doesn’t change.

How has the decision to go no-contact with your parents affected your life?

It was a master class in guilt and in learning to get over and give up on guilt. When people assume that guilt has utility, I think it’s because what they’re really pointing to is that compassion has utility. So, in other words, if I hurt a friend’s feelings, if I can open myself to the true compassion of understanding how they’ve been hurt, this will change my behavior. Feeling guilty and bad doesn’t change behavior and isn’t worth it.

What you’re saying about compassion is making me think about the letters to the younger Jeffreys in your book. What was it like to write those letters to yourselves?

Cathartic. It was exciting. It was nice. It was wonderful. It was heart-opening, and it was healing. I decided that in addition to talking about 6-year-old Jeffrey, 13-year-old Jeffrey, and 18-year-old Jeffrey, I could thank them: I could write to them and tell them how I feel. And it wasn’t clear whether I would include those letters in the book, but my publisher liked that idea. So kudos to Penguin for suggesting that they go in because it’s been healing for a lot of people. I get emails about those letters a lot.

What was your writing process like?

I wanted this book to flow like a conversation with a friend. Someone told me, “It feels like I’m on a river and you’re just guiding me along.” So the real genesis of the book was to make recordings as if I was talking to a friend, and then taking those recordings, transcribing them, and working with them to create the text that eventually made its way into the book. Hopefully, what has been kept in that process is the real familiar feeling and the kind, inviting tone of the book. And that’s because, in a way, that’s my signature: people are drawn to my work because of that friendly feeling and knowing that they’re included and that we’re connecting. So I had to approach the book in a way that would preserve that.

photo credit: Jeff E Photo

There’s a section in your book where you delve into what it means to be an authority. And I found myself thinking about the similarity between the words author, authority, and authenticity. What has been your journey into stepping into the authority of your authenticity?

That is the only way we can do it. It is possible, obviously, to be an authority on a subject–to be a subject matter expert. That happens all the time. But there is no one else that is an authority on your experience, on your worldview, on the things that have shaped what you care about. So to me, one thing that’s essential is accepting that you are an authority. You are an author of this human being’s outlook, and you can make conscious choices to express that in ways that help bring people together.

How do you accept that you are an authority?

Well, I talk about this a little bit in the book, but I despise the phrase “fake it till you make it,” because ultimately it’s not fake. So it’s more like: “Real it until you make it.” It’s more like: “Express what is real and true, even if you have internal programming fighting against you.” And eventually you will wear down that programming. And the good news is you will live constantly in the truth.

In a TED Talk you gave, you said that: “The thing that you were taught is most wrong with you is your greatest asset as an activist.” How and when did you begin to discover this for yourself?

I began to discover this because being me is fun, to be honest. I was famous on Vine, this would be a decade ago, and those videos were six and a half seconds long. And what six and a half seconds allowed me to do was have just enough time to say, “There is nothing wrong with you” to the camera, which is a complete distillation of who I am and what I’m trying to do here. And then I really began to devote my entire life, my work, and my career, to that. Of course, I had the spiritual foundation of being a Buddhist. Making Vines was the real-world version of this. And I’ll tell you, back on Vine, it was a little Wild Westy. You couldn’t block people, you couldn’t delete somebody’s comments, and you couldn’t filter words. It was an experience, shall we say. And I thought many a time: “Do I want other LGBTQ people, or just other people in general, to see someone like me constantly getting hate, day after day after day?” And then I realized: that is also part of the mission. That’s also part of the point: that I would post one day, get hate, and then post the next day, and then post again, and then post again–this was part of the process. In short, what I do is not for them or about them.

I watched the interview you did with Newsmax, and I really admired your grace when confronted with disrespectful questions. How do you protect your spirit in hostile spaces?

Yeah, Newsmax was hostile. This was years ago, pre-pandemic, my first book had just come out, and I thought: “Well, if my mission is to reach people, then I might reach somebody.” And that seemed reasonable at the time, but Newsmax was not a fun environment. They were anti-Jeffrey and anti-LGBTQ people. And the way I protected myself was to say nice things to myself. So we’re on set, and I’m sitting there by myself. There are sound people, camera people, but it’s basically just me and the host. We are about to do the segment and I’m saying to myself: “Thank you, Jeffrey. This is so important. I’m so glad you’re here. I love you. Let’s do something fun afterward.” This is the way that I talk to myself. And then when the red light goes on, on top of the camera, and it’s time to go, I’m already in that space. And even if the interviewer wants to pull me from that space, that’s where the real work begins–practicing not allowing that to happen.

It reminds me of what you wrote, about how it is impossible to nail Jell-O to a wall.

Yeah. A fight takes two people, and my teacher at the monastery would liken it to asking someone to nail Jell-O to the wall. Someone looking for a fight wants resistance so that their nail has someplace to be and they can bang away with their hammer. But if it’s like Jell-O and you just relax into what you’re there to do, which in my case was love and kindness, then they’re not meeting resistance. And there’s very little they can do with that.

In an interview with PBS, you invited the interviewer to describe you in a word, and he said “light.” And then you said: “Well, you just described yourself.” I was curious about how you came to this understanding–that you are a mirror.

I realized quite a long time ago that my mission in life is to draw out what needs to be healed in people. Sometimes that is a great thing if they are in a place where that is what they want. But sometimes it gets ugly: I draw out their bigotry or whatever they need to get over in order to have peace in their lives. And they rebel, which is understandable. But my mission doesn’t change. What I’m here to do doesn’t change. And what I hope to be is a bookmark for unconditional love and acceptance until people realize that unconditional love is actually within them and has been the whole time. I’m always pointing people toward the realization that whatever they see in me is because they have it already.

Was understanding that you are a mirror a gradual realization?

I first learned about the principle of projection at the monastery, twenty-ish years ago, and it’s also a Western therapy concept. But it gets close to the Buddhist idea of oneness: that there’s nothing in me that’s not in you, that we’re connected in that way. It’s still a process of it settling in and becoming a daily practice, to remember that and to celebrate it.

Would you speak about the role of humor and laughter in your work?

I find humor essential, and I’m not the only one. Often, in all kinds of world religions, there is a role for a joker, for someone who turns reality on its head. And not for nothing, this is a role that trans people fulfill in society. Often people want to make it extremely serious, and I disagree. We should show up, we shouldn’t shirk our duties, but we absolutely need to have fun while we’re doing it. It doesn’t make sense to me otherwise.

When was the first time you felt like you belonged and that you were loved exactly as you are?

Actually, when I was a kid, I would dance and twirl around in our barn and pretend to be Julie Andrews. I felt like I created the loving family I always wanted, in this imaginary plane, because I was pretending to be Julie Andrews, but with an audience who loved me–with a family sitting around who was encouraging me and loving me. So it was sort of like a coping mechanism, but it also strikes me as being very LGBTQ. So many of us patch together the self-esteem, the kindness, the chosen family, the support system we need. We just gather dribs and drabs and little pieces from here and there and craft a full, beautiful quilt of a life from the ground up. Which actually sounds like a burden, but it is a blessing. So many people think that they have a support system or assume that they’re doing amazing because they happen to fit what society wants in one way or another. But so much of being an LGBTQ person is being an outsider. And I felt like an outsider even when I was a kid. But the benefit of being an outsider is that you know the system is fake.

So this sense of belonging and being loved was self-generated and had less to do with other people saying that you belonged?

I think it’s kind of both. Let’s be really ultra-clear: you can’t have transformations without other people. This is something the Buddha directly talked about. One of the three jewels of practice is practicing with a religious group, with other people, because you need those mirrors from others. And the hermit lifestyle is fine for some religious folks, but usually, when you have a group of people around, you get inspired, you feel connected, you feel that sense of belonging, and you grow. And that must be paired, in a nonbinary way, with work on the inside and choosing to grow yourself.

photo credit: Tomoki Kawa

I would like to ask you about anger. You write: “At its best, anger is a call to fairness and a hand stretched out in your direction, an invitation to honor how much you care.” How do you distinguish between generative anger and destructive anger?

Yes–what we might call righteous anger versus run-of-the-mill hate. To me, I think they’re one and the same. I’m going to give you a very non-binary answer: constructive and destructive anger both spring out of a sense of injustice. I would imagine that someone hateful hates me because there is some sense that my freedom is not available to them, which is an injustice: that I’m getting attention, that I deeply love myself, and that they’re not allowed to. And that sense of injustice creates a lot of anger, just from what I’ve observed. But anger can be a source for good because there’s a lot of injustice that ought to be overturned in this world. Anger is a friend. Anger is trying to tell you something. Jesus got very angry in the Bible, famously. And that story, as far as I understand it, is about injustice. So anger is human. Anger is a kindness. For so many of us who have been traumatized, the worst thing we can think of is inflicting trauma on other people. We tend to associate anger with one or both of our parents being very traumatic, violent, hateful, mean, being the chaos. And if you break anger away from those associations, it really is a story of injustice and sensations in your body. So anger can really be an invitation.

A word I’ve seen surface in your work is “nonviolence.” What does this idea mean to you?

I’m committed to nonviolence both internally and externally. And as we were discussing before, you almost can’t have one without the other. You can’t do activism to end the violence in the world without ending the internal violence as well.

What does it look like to be nonviolent with yourself?

Unconditional love. These phrases get thrown around and I’m guessing some people reading may be rolling their eyes. But what I mean is: even if something happens that doesn’t go well, even if you have feelings, you have trauma, you have things that are coming up…can you love yourself in every single situation? To me, judging yourself, hating yourself, those voices inside your head saying, “Why’d you do that?”, “They’re going to laugh at you,” “You’re so stupid”– that’s internal violence And if you’re going to commit yourself to nonviolence and commit yourself to be nonviolent in every possible situation, that is a wide-open invitation for life to bring in things that may challenge you because you’ve committed to facing challenges.

What do you do when you start to hear that inner voice of violence?

You have several options. You can turn your attention to something else, which gets easier over time. So, you could treat the things I was saying on the set of Newsmax as a mantra: “Thank you. I love you. I’m so glad you’re here. Thank you. I love you. I’m so glad you’re here.” Just repeat, repeat, repeat. And as best as you can, turn your attention to that and away from the nasty voices in your head. The other thing to do, if that doesn’t seem available, is to start asking that voice questions. So, say something goes wrong at work. You send out an email and it’s the most important email, and it has a typo in it. And all of a sudden there are voices inside your head going: “Oh, how could you? You’re going to get fired. They hate you now. Now they know how awful you are.” All of that starts up. You do have the option–not a lot of people are aware–but you do have the option to turn around and say: “How do you know that? Who said that? Could you give me some proof of this?”

There seems to be a false idea: that I can speak to myself unkindly, but be kind to others, simultaneously.

A lot of people think the best way to be kind to others is to beat yourself into being kind. And this is where we get into what might sound like Dr. Phil territory, or Oprah in the nineties territory, with the idea of “put yourself first.” This is a solid spiritual principle, but it gets eye-rolly very fast. So to add some depth and context to that principle: if there is a choice point, choose yourself. And if there’s no choice point, then choose everyone, which includes yourself. And eventually, we learn that very often choosing ourselves is what’s kindest for all.

Another word that stood out to me in your book is “sparkle.” What does it mean for you to sparkle?

Well, people tell me I’m brave, and it’s the sparkly eyeshadow and the sparkly lip gloss, for sure. But there’s also a sparkle in having fun. People get the idea that I don’t take them very seriously, and it’s true, I don’t. I don’t take myself seriously, either. I take somebody’s true heart or essence or the core of their soul very seriously. But the trappings, the things we were taught, the things we’re all supposed to be trying to do to compensate for how awful we feel, and all those things that everybody wraps up their lives in, I don’t take that stuff very seriously at all. And I think it’s important to have fun and joke around as part of spiritual growth, And to me, the best way that you can take care of yourself is to embrace the unbearable lightness of being that’s sparkling. We’re not here for a long time.

How would you like to be remembered?

I would like to be remembered as a bookmark for the unconditional. After I am gone, I hope that anybody who knew me personally, or on the Internet, or through my life and work, will take from me an overwhelming sense that there is nothing wrong with them.

In the epilogue of your book, you write a letter to your 44-year-old self, in which you say: “I also know that you don’t talk much about the positive emails you get every day. You don’t talk about the emails that say, you saved my life.” What does it mean for little Jeffrey to know that big Jeffrey receives these emails?

It’s deeply important. So on one level, little Jeffrey doesn’t check the inbox and is just dancing around and having fun. But I think the importance of the impact and the fun I get to have is very much little Jeffrey. I was surprised and delighted that little Jeffrey taught me things, inspired me, helped me to have peace and to heal. And that there is a version of this inner child, this little Jeffrey, who is frozen in time and out of time when life was beautiful and innocent, lovely and colorful and wonderful. And little Jeffrey has stayed the bookmark into my adulthood to remind me that those things are there and worthwhile and fun and beautiful.

So little Jeffrey holds the sparkle, the laughter?

Yeah, to a large extent. And Little Jeffrey has taught me, adult me, to sparkle more.