The Goal Is To Be Forgotten

In Conversation with Jen Richards

Photo by Ryan Pfluger

Jen Richards is a writer and actress, as well as a consultant and advocate. She can currently be seen in the independent feature Gossamer Folds. Prior to that, she played opposite Kathryn Hahn in the HBO series Mrs. Fletcher. She also played the lead in a critically acclaimed episode of Netflix’s revival of Tales of the City, which looks back at a young Anna Madrigal (played by Olympia Dukakis) arriving in 1960’s San Francisco.

She has guest-starred and recurred on several popular broadcast and cable shows including Better Things, Blindspot, Doubt, and Nashville. As a creator, she was nominated for an Emmy for her digital series, Her Story, about the dating lives of trans women, which she wrote, produced, and starred in. She is currently writing projects for Sarah Jessica Parker’s company, Pretty Matches, and a project for Sony produced by Gabrielle Union. She was also recently seen in the Netflix documentary Disclosure, which looks at the history of transgender depictions in film and television.

We spent an hour talking to Jen about Shakespeare, joy, rage, writing, and the fact that each of us has a moral responsibility to allow room for redemption in everything we create. The following interview has been condensed for clarity; to learn more about Jen and her ongoing work visit her website.

Interviewed by Billy Lezra and Liam Lezra | August 11, 2020

We’d love to start with Shakespeare. What is it about the work that you find compelling in particular?

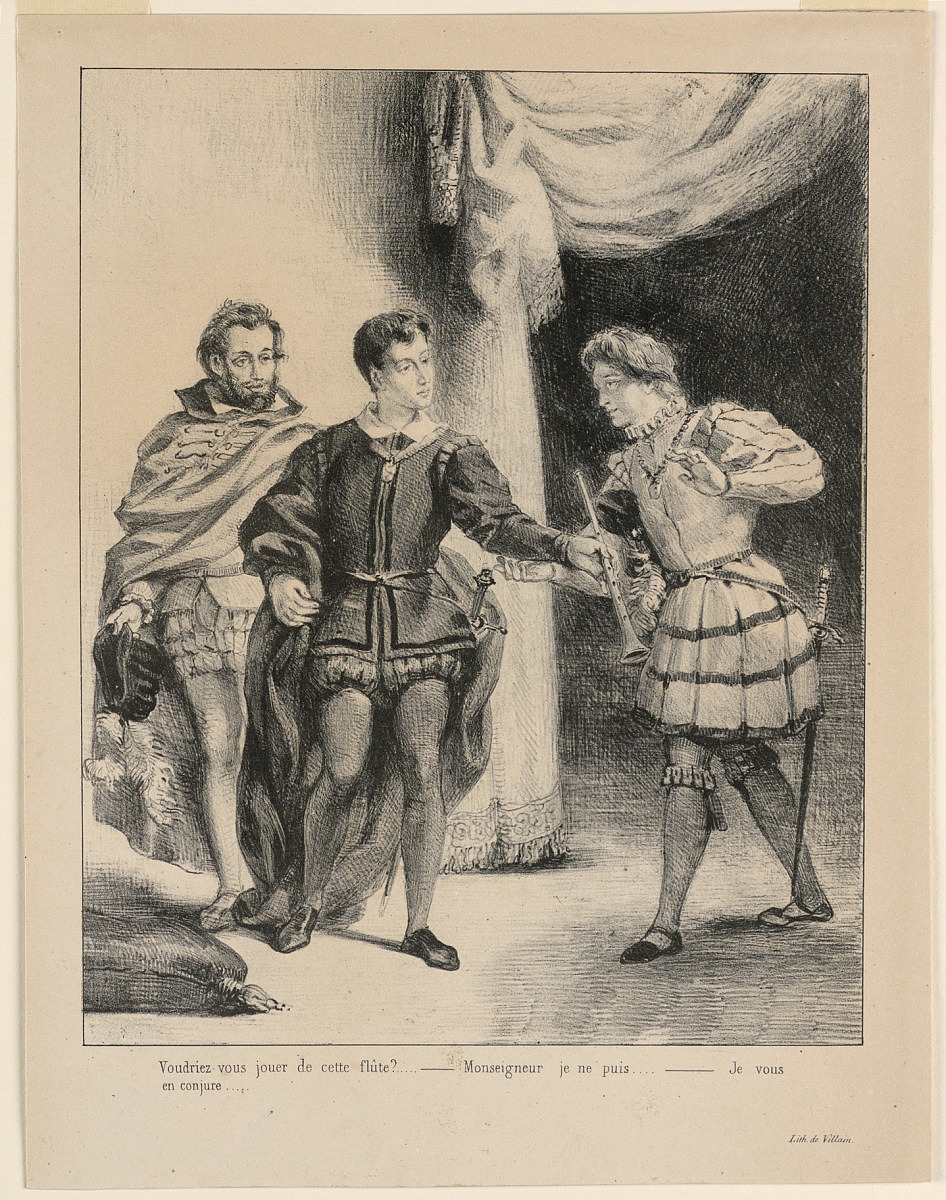

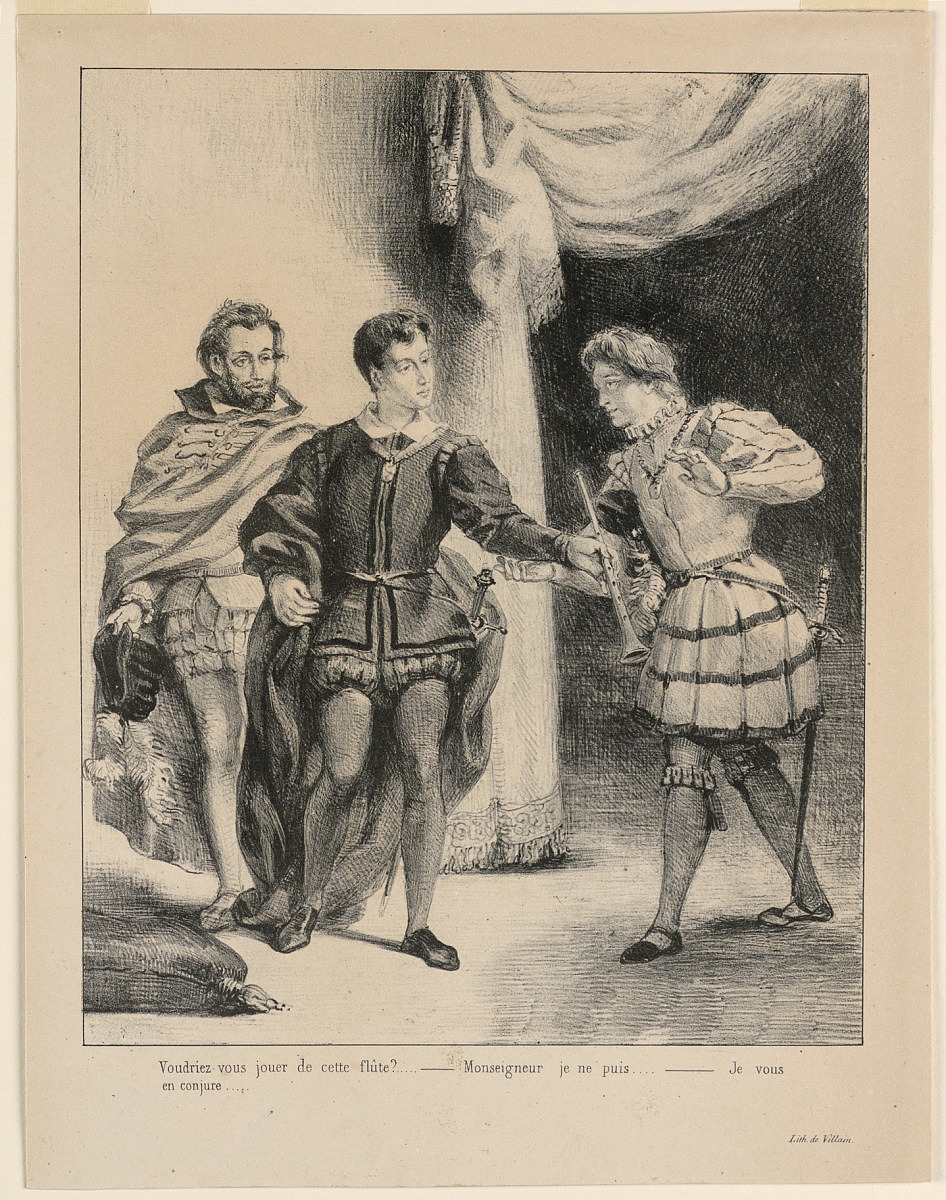

It is hard not to love Shakespeare, as a lover of language, character, and of story. Shakespeare is like wine or tea; one of those things that you can spend a lifetime on. Every time you go through it, it gets deeper and deeper.

Hamlet became the story that sustained me over the years. Whenever there is a production, I see it. That work’s capacity for different interpretations and different perspectives astonishes me.

Hamlet in particular is someone who has this duty. Humans are simply sophisticated animals in so many ways; one of the ways this shows up is in our desire for vengeance. Cultures have tried to break and end the cycles of vengeance through law and through the monopolization of violence. In Hamlet, this becomes internalized into a person.

Essentially, Hamlet is a philosopher. He is reflective in a way not typical of protagonists before that time. This character—who has all the right to want vengeance and is told to avenge his father’s death by his father’s ghost—can’t quite do it. Fundamentally, he is an artist; he loves the theater. Instead of acting, he delivers incredible soliloquies on what it means to be human and alive. And yet he can never truly act.

Part of the mystery of Hamlet is understanding what drives his ennui and despair, and the question of: is he going crazy or not? How much of this is feigned and how much is intentional? There are all these incredible clues in the text itself. One interpretation I would like to stage is to have Hamlet as a trans woman. What drives Hamlet’s discomfort in the world with his role as the son is that he is really a woman. It creates an almost triple-entendre.

“Not so, my lord. I am too much i’ the sun,” one of the very first lines Hamlet says, is a double-entendre. Hamlet doesn’t want to step into the light. He is also a son, as in a burden, as in: “I don’t want to be the son because my father is dead.” I think you can add this triple layer of: “I don’t want to be a man. I don’t want to be this person who has to continue the cycle of male violence.” In this interpretation, I want to have Hamlet in love with Horatio. It’s not that he is in love with Ophelia—he envies Ophelia’s feminine innocence and the fact that she can exist in a world where she is not circumscribed by male patterns of violence.

There is this great scene where Hamlet appears to Ophelia kind of mad, garters all crisscrossed. We don’t actually see it, but we see Ophelia talking to the King and Queen about it. I thought: if we don’t see it, what if what Ophelia is struggling to describe is Hamlet in drag? What if Hamlet comes to her dressed as a woman and Ophelia is just like, “I don’t know how to tell the King and Queen this…” so instead, in a circumscribed way, she says: “he was dressing all funny and acting all funny…”

There’s a weird passage later on, where Hamlet’s ships get taken by pirates. For some reason, Hamlet is allowed to live. In my mind, it is because Hamlet was in drag. He became the captain’s bitch, basically. That’s how he survived.

The tragic turn in the final act is Hamlet finally realizing that he can’t do it anymore. He has to be a man and put the feminine shit aside and go do his duty as a son. That is the added tragedy. There are some great lines at the very end between Horatio and Hamlet where they essentially say that the story you have just seen is only the surface. Hamlet owns that he can’t change himself; that he is a man that has to do what a man does: that is part of the tragic ending.

As you talk about Hamlet, I can imagine what it must have been like to discuss the Great Books with you at Shimer College. What was the experience like for you?

I absolutely loved every minute of it. If I had the time and money, I would do the whole program again. For four years there are no textbooks, no lectures, and no tests. All you do is read original source material, discuss it in class, and write papers.

Half your grade is papers and half your grade is discussion. The average class size is five or six students. You couldn’t hide. You had to know the material and be prepared with an interpretation, an argument, and a defense. If you are studying mathematics you’re reading Euclid’s principles, if you are doing evolution you’re reading Darwin, if you’re doing psychology you are reading Freud and Jung.

There are some places where this pedagogical approach is to better understand the canon. There is another approach, the Shimer approach, where you use the canon to facilitate great conversations. It is ultimately about critical thinking; as you move forward, you realize that everything is a text. A movie is a text, a TV show, a new album, a presidential speech, discourse on twitter, a meme. They are all texts. I feel confident in my ability to read those as texts and to have an interpretation, and to engage in a conversation about them.

How did you decide to study at Shimer?

I left home at nineteen. I didn’t go to college. I was working full-time. I basically just studied at the community college and learned Sanskrit and Japanese, and did other stuff just for fun. It got to a point where I realized that I wasn’t going to move forward in life unless I had a degree. There was a limit to how much I could teach myself. I checked out a bunch of colleges; I didn’t like them; they felt like big parties, big social experiments. I came across an advertisement for Shimer College in a New Age magazine in Chicago called Conscious Choice.

I was working at a book-store at the time, and I opened the magazine. The top right half-panel had a picture with two people looking out opposite windows. In the middle, it read “great minds don’t think alike.” That intrigued me. They had a program for working adults; I could go on the weekends, so I could keep working full-time. I went up there and sat in on a class with eight students and a teacher. They were passionately arguing about King Lear and I was like, “Where am I?” This is where I want to be. I signed up and did it.

In Her Story, Violet asks Allie what her first battle was. What was your first battle?

That was it. The one Allie says was verbatim from my history. When I was fifteen there was an underground paper in my high school called The Progressive Flyer. It had been going on for years. This was back in the day when you print something out, cut it, and paste it onto a master sheet and photo-copy it. Zines, basically. It was usually a group of seniors who did it. I fell in with that group of seniors when I was a junior because we were all in theater together. So when they graduated, I corralled a bunch of my friends and we took over.

One day there was a sex-ed demonstration during the height of AIDS. A student asked how to put on a condom. The people leading the demonstration were so embarrassed and were like, “Oh, ask us later.” It was ridiculous. It was a matter of life and death. So The Progressive Flyer did a whole issue on sex education with actual instructions on how to put on a condom. I felt that we had an opportunity to do real things.

Then a good friend of mine told me that her Spanish teacher was sexually harassing her. I heard about three teachers in particular that several girls I knew were suffering under. It infuriated me. It seemed so wrong. I didn’t know what to do about it so I specifically wrote out three accounts of different students and what the teachers had done; I didn’t name the teachers. The very next day the principal held an all-staff meeting and the students caught wind of it. And all the teachers stopped doing it. I was fifteen and I had written a story that had made the world slightly better for some people. I could change the world for the better just through words. It shaped me for life.

You said that crafting the script for Her Story was about fidelity to the truth of your and Angelica’s experiences, and wanting to keep it as authentic as possible. How did you know when you’d hit an authentic scene?

There is an emotional resonance first and foremost, with the actors. For Angelica and I, if it is hard to do, it is a pretty good indication that there is something here. Some of the scenes were hard to film. There was a scene where Paige and I were talking about her date with James, and why she didn’t come out to him. She says this line: “for a moment I just wanted to be a girl on a date.” The scene ended up being redundant so we cut it, but Sydney, our director, had Angelica keep saying the line for different takes. And Angelica finally just broke down because it was real for her. She wanted to have that experience of just being a girl on a date. And in my scene with Mark, some of it was improvised. Sydney had us keep going through it and pushing it further until we were fighting. I had a breakdown after that scene. That’s a big indicator.

When we started screening it, I would look for the trans people in the audience and see how they responded. People would come up to me after, in tears, and talk about their experiences. That’s when you know.

At that point, when Her Story came out, I don’t think any of us had ever seen literally anything that was actually about, written, and performed by trans people. And to finally see that in such an emotionally engaging visceral way was profoundly cathartic for trans people, specifically. It ended up resonating with lots of different kinds of people, which was incredible, but that is whose responses matter the most to me.

What is your relationship to rage?

I suppose it is more of a compass now. When the anger comes out it is an indication of real injustice. I think things should be fair, and it really bothers me when they are not. When I was younger a lot of my rage was fueled by personal trauma. The only two authentic states of being were raging at the injustice in the world or complete exhaustion because you’ve worked so hard, and you have been so angry that you are completely depleted and physically and psychologically incapable of doing anything else. That’s not true for me anymore. At my age, I have gone through therapy, sobriety, and all these things that have healed my personal rage. I like creature comforts. I am happily in a relationship. I spend a lot of time just gardening, sipping tea, enjoying art and media. But the rage is still a compass point for me.

As an activist and an educator, how do you distinguish between a teachable moment and a non-teachable moment? Is there such a thing as a non-teachable moment?

I can generally tell when someone has an open mind or genuinely doesn’t understand something and wants to, as opposed to when they have already made up their mind and they are there to harass or hurt you. I said something about J.K. Rowling, and this one person started asking me questions. At first, they were a bit aggressive, but there was something in their tone and the way that they phrased things that made me think that they genuinely wanted to understand. I went back and forth with them for a long time. In the end, I don’t know that we agreed with each other, but they certainly understood my perspective. I think their position was softened.

But then with other people…if you fundamentally think that I am a man and you are going to see everything through that lens, there is no point in that conversation except inasmuch as it is theater for the people that are watching, which can sometimes have value for the people who will learn from the arguments and the points that you make. I don’t always have the energy for that. For the most part, I am not going to argue about my humanity. I am not going to argue with people who don’t believe in science or facts. It’s just a waste of my time.

Photo by Levi J. Foster

I remember some years ago I wrote an article and there was a discussion about it. I went into the comments to start arguing. I had an aha moment. You can either be in the comments arguing, or you can be what they are arguing about, but you can’t be both. There was a talk by Brené Brown that absolutely changed my life. After her first big TED talk went viral, she saw a lot of awful comments that really upset her. This talk is about what she learned from that. She quoted Theodore Roosevelt:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds.”

Basically, it finally gave me permission to ignore anyone who doesn’t know what they are talking about. It is not to say that you are immune to criticism. But if it is just people that are yelling in the stands who haven’t done it and don’t know what it is, I just have no interest in it. It is noise.

Part of the consequence of our culture today with social media is that we lose context. Language is really interesting. There has always been a divide between spoken language and written language. People were often skeptical even of the earliest written languages.

If we are in conversation, there is a specific context. There is a tone to our conversation, we are seeing each other, there is body language, there is our relationship: there is a context in which we are saying everything. Some things are forgiven, softened, enhanced. Writing removes all that context, which can be really dangerous.

What concerns me about social media is that we use it as speech, but it is consumed as writing. We are conflating these two things that have traditionally been very separate. A novel creates its own world. All its lack of context is mitigated by its internal context. Without all the context you might get from a novel or a conversation, things sound really different. That is what is really precarious.

What is the relationship between faith, spirituality, and activism for you?

Not only do I think justice is possible—I think redemption is possible. I think we are put here for a purpose. Every one of us is an utterly unique being. Even if reincarnation is true, the fact is that I will only be this person in this time, in this place, once, in an infinite expanse of space and time, which is pretty astonishing. It is one of the most fundamental truths of the universe—the uniqueness of every single thing. To me, that is an indication of moral importance.

We have a moral responsibility to become the most ourselves we can be. In order to do that, I think kindness, justice, compassion, empathy, art, truth, and beauty better facilitate our ability to be uniquely ourselves than do injustice, cruelty, acrimony, lies, etc. It is more of a function of how we fulfill our purpose. In that sense, faith and spirituality motivate my sense of justice.

Photo by John Sturdy

What are the qualities you look for in a friend?

A certain baseline honesty and transparency and authenticity. A certain curiosity. I am generally only interested in people that are genuinely curious about the world and about themselves. I like people with zest for life, who have a sense of purpose, who have joy.

There is a Vedic concept of Satchitananda, a Sanskrit compound of three words that are supposedly the three fundamental aspects of existence. Sat is to be. Chit is to be conscious. Ananda is to be joyous. These three things are the Eastern analogs of the Western idea of the good, the true, and the beautiful. These three things are fundamental about life and they are inseparable. To be good is to be true and beautiful. To be is to be conscious, is to be joyful. The people that shine in the dark for me are those who have a certain kind of consciousness and mindfulness about being alive. There is a fundamental quality of joy.

The friends I have are the most amazing people I have ever met. They bring me so much joy and comfort. In particular, there is a group of six of us who are on a constant text chain. It is the first time in my adult life that I have found a group of people where I completely trust and know that they will always be there for me, and I will always be there for them.

Where do you go to find hope?

I never not see hope. There was a study that came out that reviewed hundreds and hundreds of closed-circuit television videos. When something goes wrong, the vast majority of people jump in to help. We are so accustomed to seeing the worst of things that it is easy to forget how generally good people really are, and I don’t mean that blithely. I have had friends that have gone through things that are truly horrific. I think it is very understandable and easy to have your perspective and worldview defined by the horror that we see. It does often taint me. Part of self-care if choosing to look for the good, the positive, and the beautiful.

I lived in a spiritual commune when I was young, for several years. Jan Phillips had a book called “Speaking to the Muse,” about getting in touch with yourself and your creativity. During our workshop, she said that we have a moral responsibility to allow for redemption in anything we create because in life there is always an opportunity for redemption. We have a moral responsibility as artists to include this in our work. That became a real touchstone for me. No matter what I do there is hope, and there is an opportunity for redemption. I don’t have a lot of tolerance for nihilistic art that doesn’t allow for that.

How would you like to be remembered?

I don’t know that I care. I want the people who are in my life to smile when they think of me after I am gone. I’d be happy with that. I have sometimes joked, when it comes to activism work or social justice work, that the goal is to be forgotten. If you’ve really worked on an issue to the point that it is erased, then people forgot that it was an issue. They don’t think about you. The fact that right now it is kind of taken as a given that trans people should play trans parts in movies and TV shows is something I worked really, really hard on. I want some kid to just take it for granted. A lot of people take for granted that trans healthcare should be provided by insurance. That is great. That means we did our job. I hope to be forgotten in that sense.

Photo by Christina Gandolfo (cgandolfo.com)

To learn more about Jen and her work, visit her website.

The Goal Is To Be Forgotten

In Conversation with Jen Richards

Photo by Ryan Pfluger

Jen Richards is a writer and actress, as well as a consultant and advocate. She can currently be seen in the independent feature Gossamer Folds. Prior to that, she played opposite Kathryn Hahn in the HBO series Mrs. Fletcher. She also played the lead in a critically acclaimed episode of Netflix’s revival of Tales of the City, which looks back at a young Anna Madrigal (played by Olympia Dukakis) arriving in 1960’s San Francisco.

She has guest-starred and recurred on several popular broadcast and cable shows including Better Things, Blindspot, Doubt, and Nashville. As a creator, she was nominated for an Emmy for her digital series, Her Story, about the dating lives of trans women, which she wrote, produced, and starred in. She is currently writing projects for Sarah Jessica Parker’s company, Pretty Matches, and a project for Sony produced by Gabrielle Union. She was also recently seen in the Netflix documentary Disclosure, which looks at the history of transgender depictions in film and television.

We spent an hour talking to Jen about Shakespeare, joy, rage, writing, and the fact that each of us has a moral responsibility to allow room for redemption in everything we create. The following interview has been condensed for clarity; to learn more about Jen and her ongoing work visit her website.

Interviewed by Billy Lezra and Liam Lezra | August 11, 2020

We’d love to start with Shakespeare. What is it about the work that you find compelling in particular?

It is hard not to love Shakespeare, as a lover of language, character, and of story. Shakespeare is like wine or tea; one of those things that you can spend a lifetime on. Every time you go through it, it gets deeper and deeper.

Hamlet became the story that sustained me over the years. Whenever there is a production, I see it. That work’s capacity for different interpretations and different perspectives astonishes me.

Hamlet in particular is someone who has this duty. Humans are simply sophisticated animals in so many ways; one of the ways this shows up is in our desire for vengeance. Cultures have tried to break and end the cycles of vengeance through law and through the monopolization of violence. In Hamlet, this becomes internalized into a person.

Essentially, Hamlet is a philosopher. He is reflective in a way not typical of protagonists before that time. This character—who has all the right to want vengeance and is told to avenge his father’s death by his father’s ghost—can’t quite do it. Fundamentally, he is an artist; he loves the theater. Instead of acting, he delivers incredible soliloquies on what it means to be human and alive. And yet he can never truly act.

Part of the mystery of Hamlet is understanding what drives his ennui and despair, and the question of: is he going crazy or not? How much of this is feigned and how much is intentional? There are all these incredible clues in the text itself. One interpretation I would like to stage is to have Hamlet as a trans woman. What drives Hamlet’s discomfort in the world with his role as the son is that he is really a woman. It creates an almost triple-entendre.

“Not so, my lord. I am too much i’ the sun,” one of the very first lines Hamlet says, is a double-entendre. Hamlet doesn’t want to step into the light. He is also a son, as in a burden, as in: “I don’t want to be the son because my father is dead.” I think you can add this triple layer of: “I don’t want to be a man. I don’t want to be this person who has to continue the cycle of male violence.” In this interpretation, I want to have Hamlet in love with Horatio. It’s not that he is in love with Ophelia—he envies Ophelia’s feminine innocence and the fact that she can exist in a world where she is not circumscribed by male patterns of violence.

There is this great scene where Hamlet appears to Ophelia kind of mad, garters all crisscrossed. We don’t actually see it, but we see Ophelia talking to the King and Queen about it. I thought: if we don’t see it, what if what Ophelia is struggling to describe is Hamlet in drag? What if Hamlet comes to her dressed as a woman and Ophelia is just like, “I don’t know how to tell the King and Queen this…” so instead, in a circumscribed way, she says: “he was dressing all funny and acting all funny…”

There’s a weird passage later on, where Hamlet’s ships get taken by pirates. For some reason, Hamlet is allowed to live. In my mind, it is because Hamlet was in drag. He became the captain’s bitch, basically. That’s how he survived.

The tragic turn in the final act is Hamlet finally realizing that he can’t do it anymore. He has to be a man and put the feminine shit aside and go do his duty as a son. That is the added tragedy. There are some great lines at the very end between Horatio and Hamlet where they essentially say that the story you have just seen is only the surface. Hamlet owns that he can’t change himself; that he is a man that has to do what a man does: that is part of the tragic ending.

As you talk about Hamlet, I can imagine what it must have been like to discuss the Great Books with you at Shimer College. What was the experience like for you?

I absolutely loved every minute of it. If I had the time and money, I would do the whole program again. For four years there are no textbooks, no lectures, and no tests. All you do is read original source material, discuss it in class, and write papers.

Half your grade is papers and half your grade is discussion. The average class size is five or six students. You couldn’t hide. You had to know the material and be prepared with an interpretation, an argument, and a defense. If you are studying mathematics you’re reading Euclid’s principles, if you are doing evolution you’re reading Darwin, if you’re doing psychology you are reading Freud and Jung.

There are some places where this pedagogical approach is to better understand the canon. There is another approach, the Shimer approach, where you use the canon to facilitate great conversations. It is ultimately about critical thinking; as you move forward, you realize that everything is a text. A movie is a text, a TV show, a new album, a presidential speech, discourse on twitter, a meme. They are all texts. I feel confident in my ability to read those as texts and to have an interpretation, and to engage in a conversation about them.

How did you decide to study at Shimer?

I left home at nineteen. I didn’t go to college. I was working full-time. I basically just studied at the community college and learned Sanskrit and Japanese, and did other stuff just for fun. It got to a point where I realized that I wasn’t going to move forward in life unless I had a degree. There was a limit to how much I could teach myself. I checked out a bunch of colleges; I didn’t like them; they felt like big parties, big social experiments. I came across an advertisement for Shimer College in a New Age magazine in Chicago called Conscious Choice.

I was working at a book-store at the time, and I opened the magazine. The top right half-panel had a picture with two people looking out opposite windows. In the middle, it read “great minds don’t think alike.” That intrigued me. They had a program for working adults; I could go on the weekends, so I could keep working full-time. I went up there and sat in on a class with eight students and a teacher. They were passionately arguing about King Lear and I was like, “Where am I?” This is where I want to be. I signed up and did it.

In Her Story, Violet asks Allie what her first battle was. What was your first battle?

That was it. The one Allie says was verbatim from my history. When I was fifteen there was an underground paper in my high school called The Progressive Flyer. It had been going on for years. This was back in the day when you print something out, cut it, and paste it onto a master sheet and photo-copy it. Zines, basically. It was usually a group of seniors who did it. I fell in with that group of seniors when I was a junior because we were all in theater together. So when they graduated, I corralled a bunch of my friends and we took over.

One day there was a sex-ed demonstration during the height of AIDS. A student asked how to put on a condom. The people leading the demonstration were so embarrassed and were like, “Oh, ask us later.” It was ridiculous. It was a matter of life and death. So The Progressive Flyer did a whole issue on sex education with actual instructions on how to put on a condom. I felt that we had an opportunity to do real things.

Then a good friend of mine told me that her Spanish teacher was sexually harassing her. I heard about three teachers in particular that several girls I knew were suffering under. It infuriated me. It seemed so wrong. I didn’t know what to do about it so I specifically wrote out three accounts of different students and what the teachers had done; I didn’t name the teachers. The very next day the principal held an all-staff meeting and the students caught wind of it. And all the teachers stopped doing it. I was fifteen and I had written a story that had made the world slightly better for some people. I could change the world for the better just through words. It shaped me for life.

You said that crafting the script for Her Story was about fidelity to the truth of your and Angelica’s experiences, and wanting to keep it as authentic as possible. How did you know when you’d hit an authentic scene?

There is an emotional resonance first and foremost, with the actors. For Angelica and I, if it is hard to do, it is a pretty good indication that there is something here. Some of the scenes were hard to film. There was a scene where Paige and I were talking about her date with James, and why she didn’t come out to him. She says this line: “for a moment I just wanted to be a girl on a date.” The scene ended up being redundant so we cut it, but Sydney, our director, had Angelica keep saying the line for different takes. And Angelica finally just broke down because it was real for her. She wanted to have that experience of just being a girl on a date. And in my scene with Mark, some of it was improvised. Sydney had us keep going through it and pushing it further until we were fighting. I had a breakdown after that scene. That’s a big indicator.

When we started screening it, I would look for the trans people in the audience and see how they responded. People would come up to me after, in tears, and talk about their experiences. That’s when you know.

At that point, when Her Story came out, I don’t think any of us had ever seen literally anything that was actually about, written, and performed by trans people. And to finally see that in such an emotionally engaging visceral way was profoundly cathartic for trans people, specifically. It ended up resonating with lots of different kinds of people, which was incredible, but that is whose responses matter the most to me.

What is your relationship to rage?

I suppose it is more of a compass now. When the anger comes out it is an indication of real injustice. I think things should be fair, and it really bothers me when they are not. When I was younger a lot of my rage was fueled by personal trauma. The only two authentic states of being were raging at the injustice in the world or complete exhaustion because you’ve worked so hard, and you have been so angry that you are completely depleted and physically and psychologically incapable of doing anything else. That’s not true for me anymore. At my age, I have gone through therapy, sobriety, and all these things that have healed my personal rage. I like creature comforts. I am happily in a relationship. I spend a lot of time just gardening, sipping tea, enjoying art and media. But the rage is still a compass point for me.

As an activist and an educator, how do you distinguish between a teachable moment and a non-teachable moment? Is there such a thing as a non-teachable moment?

I can generally tell when someone has an open mind or genuinely doesn’t understand something and wants to, as opposed to when they have already made up their mind and they are there to harass or hurt you. I said something about J.K. Rowling, and this one person started asking me questions. At first, they were a bit aggressive, but there was something in their tone and the way that they phrased things that made me think that they genuinely wanted to understand. I went back and forth with them for a long time. In the end, I don’t know that we agreed with each other, but they certainly understood my perspective. I think their position was softened.

But then with other people…if you fundamentally think that I am a man and you are going to see everything through that lens, there is no point in that conversation except inasmuch as it is theater for the people that are watching, which can sometimes have value for the people who will learn from the arguments and the points that you make. I don’t always have the energy for that. For the most part, I am not going to argue about my humanity. I am not going to argue with people who don’t believe in science or facts. It’s just a waste of my time.

Photo by Levi J. Foster

I remember some years ago I wrote an article and there was a discussion about it. I went into the comments to start arguing. I had an aha moment. You can either be in the comments arguing, or you can be what they are arguing about, but you can’t be both. There was a talk by Brené Brown that absolutely changed my life. After her first big TED talk went viral, she saw a lot of awful comments that really upset her. This talk is about what she learned from that. She quoted Theodore Roosevelt:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds.”

Basically, it finally gave me permission to ignore anyone who doesn’t know what they are talking about. It is not to say that you are immune to criticism. But if it is just people that are yelling in the stands who haven’t done it and don’t know what it is, I just have no interest in it. It is noise.

Part of the consequence of our culture today with social media is that we lose context. Language is really interesting. There has always been a divide between spoken language and written language. People were often skeptical even of the earliest written languages.

If we are in conversation, there is a specific context. There is a tone to our conversation, we are seeing each other, there is body language, there is our relationship: there is a context in which we are saying everything. Some things are forgiven, softened, enhanced. Writing removes all that context, which can be really dangerous.

What concerns me about social media is that we use it as speech, but it is consumed as writing. We are conflating these two things that have traditionally been very separate. A novel creates its own world. All its lack of context is mitigated by its internal context. Without all the context you might get from a novel or a conversation, things sound really different. That is what is really precarious.

What is the relationship between faith, spirituality, and activism for you?

Not only do I think justice is possible—I think redemption is possible. I think we are put here for a purpose. Every one of us is an utterly unique being. Even if reincarnation is true, the fact is that I will only be this person in this time, in this place, once, in an infinite expanse of space and time, which is pretty astonishing. It is one of the most fundamental truths of the universe—the uniqueness of every single thing. To me, that is an indication of moral importance.

We have a moral responsibility to become the most ourselves we can be. In order to do that, I think kindness, justice, compassion, empathy, art, truth, and beauty better facilitate our ability to be uniquely ourselves than do injustice, cruelty, acrimony, lies, etc. It is more of a function of how we fulfill our purpose. In that sense, faith and spirituality motivate my sense of justice.

Photo by John Sturdy

What are the qualities you look for in a friend?

A certain baseline honesty and transparency and authenticity. A certain curiosity. I am generally only interested in people that are genuinely curious about the world and about themselves. I like people with zest for life, who have a sense of purpose, who have joy.

There is a Vedic concept of Satchitananda, a Sanskrit compound of three words that are supposedly the three fundamental aspects of existence. Sat is to be. Chit is to be conscious. Ananda is to be joyous. These three things are the Eastern analogs of the Western idea of the good, the true, and the beautiful. These three things are fundamental about life and they are inseparable. To be good is to be true and beautiful. To be is to be conscious, is to be joyful. The people that shine in the dark for me are those who have a certain kind of consciousness and mindfulness about being alive. There is a fundamental quality of joy.

The friends I have are the most amazing people I have ever met. They bring me so much joy and comfort. In particular, there is a group of six of us who are on a constant text chain. It is the first time in my adult life that I have found a group of people where I completely trust and know that they will always be there for me, and I will always be there for them.

Where do you go to find hope?

I never not see hope. There was a study that came out that reviewed hundreds and hundreds of closed-circuit television videos. When something goes wrong, the vast majority of people jump in to help. We are so accustomed to seeing the worst of things that it is easy to forget how generally good people really are, and I don’t mean that blithely. I have had friends that have gone through things that are truly horrific. I think it is very understandable and easy to have your perspective and worldview defined by the horror that we see. It does often taint me. Part of self-care if choosing to look for the good, the positive, and the beautiful.

I lived in a spiritual commune when I was young, for several years. Jan Phillips had a book called “Speaking to the Muse,” about getting in touch with yourself and your creativity. During our workshop, she said that we have a moral responsibility to allow for redemption in anything we create because in life there is always an opportunity for redemption. We have a moral responsibility as artists to include this in our work. That became a real touchstone for me. No matter what I do there is hope, and there is an opportunity for redemption. I don’t have a lot of tolerance for nihilistic art that doesn’t allow for that.

How would you like to be remembered?

I don’t know that I care. I want the people who are in my life to smile when they think of me after I am gone. I’d be happy with that. I have sometimes joked, when it comes to activism work or social justice work, that the goal is to be forgotten. If you’ve really worked on an issue to the point that it is erased, then people forgot that it was an issue. They don’t think about you. The fact that right now it is kind of taken as a given that trans people should play trans parts in movies and TV shows is something I worked really, really hard on. I want some kid to just take it for granted. A lot of people take for granted that trans healthcare should be provided by insurance. That is great. That means we did our job. I hope to be forgotten in that sense.

Photo by Christina Gandolfo (cgandolfo.com)