We can take the oppressor’s keys and hide them

In Conversation with Myriam Gurba

Billy Lezra

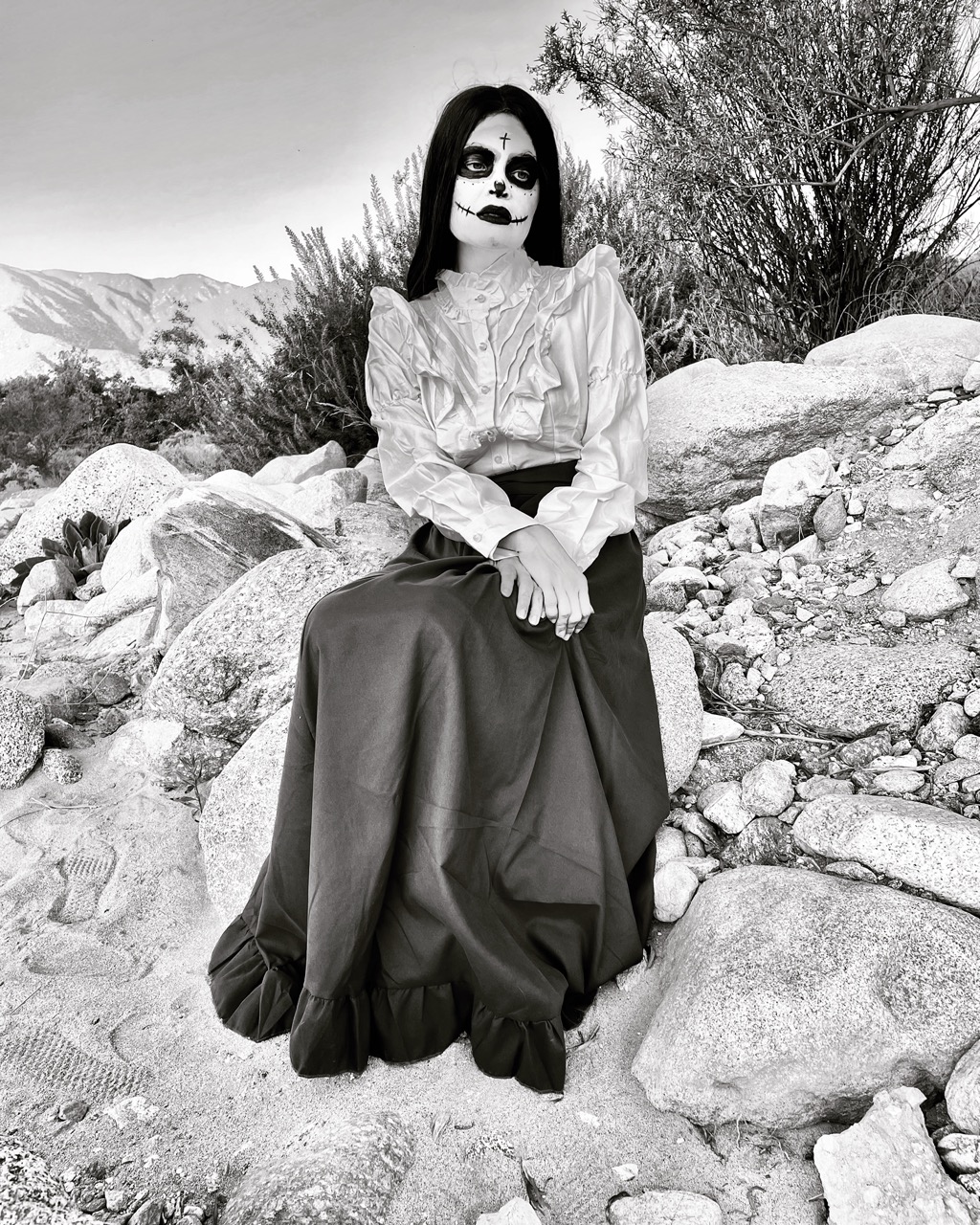

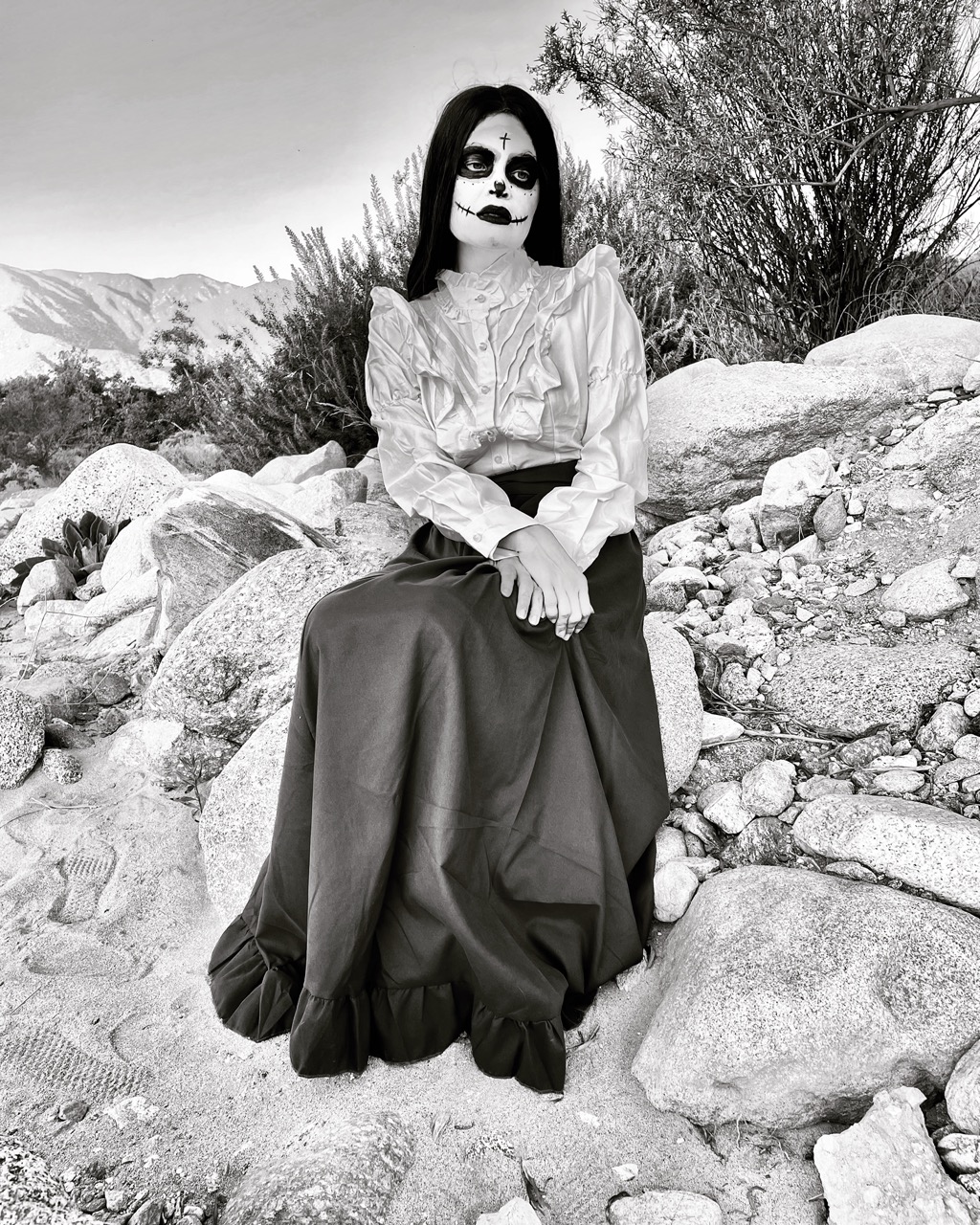

photo credit Geoff Cordner

Myriam Gurba is a writer and artist. She is the author of the true crime memoir Mean, a New York Times Editors’ Choice. O, The Oprah Magazine, ranked Mean as one of the best LGBTQ books of all time. Publishers Weekly describes Gurba as having a voice like no other. Her essays and criticism have appeared in The Paris Review, Time, and 4Columns.

Creep is Gurba’s informal sociology of creeps, a deep dive into the dark recesses of the toxic traditions that plague the United States and create the abusers who haunt our books, schools, and homes. Through cultural criticism disguised as personal essay, Gurba studies the ways in which oppression is collectively enacted, sustaining ecosystems that unfairly distribute suffering and premature death to our most vulnerable. Yet identifying individual creeps, creepy social groups, and creepy cultures is only half of this book’s project—the other half is examining how we as individuals, communities, and institutions can challenge creeps and rid ourselves of the fog that seeks to blind us.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

One of the throughlines I noticed as I was reading Creep is the rigorous act of naming–the process of identifying institutional creepdom, intimate partner violence, femicide, misogyny. How did you reach the point where you were prepared to engage in naming?

There have been various extended episodes in my life that have increasingly radicalized me. Disclosing to a former employer that I had experienced domestic violence and then being gaslit by that employer was very radicalizing and underscored my responsibility to tell the truth about my experiences. It underscored the importance of language and the importance of naming. In the “Creep” essay, the title essay, I describe both my entrapment and my escape. Language and naming were critical to my liberation. On the night that I escaped from my abuser, I fled to a friend’s home. That friend was outside the house, physically blocking my abuser from chasing me into the home. I could hear the argument that was happening outdoors: at one point my defender yelled at my abuser, “Get the fuck out of here, you are a creep.” I had not heard anybody confront my abuser, let alone appropriately name him. When I heard him appropriately labeled, appropriately categorized so loudly, because the word rang into the night, the word “creep” broke my abuser’s spell because now he was unmasked, and it was language that had done the unmasking. That evening I understood that this word could function as a verbal talisman for me. And so I grabbed onto it and used it like a torch to illuminate my way as I was writing the book.

The naming breaks the fog.

Exactly.

The image of the fog seeps through Creep. How did you land on that image?

When I set out to write the title essay, I knew that it was going to have Gothic and horror elements. I thought the essay could be an exercise in horror nonfiction, so I borrowed a lot of horror tropes and devices that take the reader to this terrified precipice. I thought quite a bit about different devices that I would introduce in order to communicate the unique horror that is intimate partner violence, because ultimately romance is used to ensnare the victim. I also wanted my starting point for that essay to be my girlhood, not the abusive relationship itself. I wanted the reader to understand that every femicide I encountered has cast a shadow across my life. Once I arrived on the precipice of becoming a victim of femicide myself, I understood that the death threats that were being issued to me were quite real, and that they were credible. All my life, women had been murdered as a result of misogyny, and I had been either a direct or indirect witness to this, which is why I include all these female figures. I’m attempting to demonstrate that, from childhood, this is something I was primed to fear, and that, in a sense, all women who learn of these femicides across our lifespans are being primed to fear them–it’s collective. So I was thinking: how can I communicate that romance is one of these weapons? Because romance is typified as soft, as caressing, as intimate, as vulnerable, as velvety. So I decided to locate the beginning of that narrative during my girlhood; my girlhood was also a time that was shrouded in fog because of where I grew up geographically. The fog was this terrifyingly soft entity that could kill people–I lost people to accidents that happened in the fog because we trusted that we knew the geography that was contained within it, because we were locals, we knew these roads. And what I’m trying to express is that you don’t know who else you’re sharing these roads with because you can’t even see your own hand, let alone your fellow traveler. So I fused that terrifying entity, that marine layer, with this notion of intimate partner violence.

Another image I noticed is the navaja, the blade, the scalpel, the knife. How this sharpness contrasts against the softness of the fog.

The image of the knife and the fascination with the knife came to me through Lorena Gallo and my interest in her. During the 1990s she became a household name; her ordeal was widely misrepresented by U.S. and international media. She was a Latin American immigrant, like my mother. I was very struck by some of the physical similarities she had to my mother. Rarely did I see, and in particular hear, women who sounded like my mother on TV. And so here’s this woman who mirrors my mother, who is testifying that she is a victim of really heinous, intimate partner violence–that her husband had raped her and that she had defended herself by essentially destroying the weapon that he was using, which was his penis. This story was so fascinating to me because I had never heard of such a thing–so many of us had never heard of such a thing. Now, as a person who is a fellow survivor and somebody who advocates on behalf of survivors, I understand that women who take action like Lorena Gallo are disproportionately punished for doing so. We’re disproportionately overrepresented in jails and prisons.

I found Lorena Gallo to be so interesting because she did not receive the standard punishment, which is incarceration. And that’s what I want for all women who engage in self-defense–I want us to be able to use the defense of violence and to be honored as women who have selves worthy of defending. This was extended to Lorena Gallo but is not extended to so many. And that’s my specific reason for invoking her. I wanted to write about her as a potential folk hero for women who are experiencing similar savagery. I wanted to propose not just a shield, but a sword, in the form of Santa Lorena.

You write: “My devotion to la Santa Muerte is why I keep a talisman of her skeletal shape close to my pillow.” Would you speak more about this devotion?

For a long time, I was a little frightened of Santa Muerte. The press has done a fantastic job of stigmatizing her and of framing her as a narco folk saint. She sits on the pantheon alongside Malverde. She has an enormous cult following of women, in particular women who appeal to her as a romantic intercessor. She also has a great deal of appeal among those of us who have been exiled from the Catholic Church. Queer and trans folk also venerate her because Santa Muerte welcomes everybody; none of us are going to escape her kiss.There’s nobody who’s going to sit on her sidelines–we’re all getting on this train. And so in that sense, she’s wonderfully democratic. Once I began to understand her in that way, I began to experiment with venerating her and became quite comfortable doing so. Then I came to realize that perhaps I’ve been on a trajectory my entire life that has been calling me toward her because I was a teenage goth! I just didn’t know what shrine I was on my way to. And now I know. I’m no longer afraid of her, and I make appeals to her. I find her so compelling and so interesting because her origins are so foggy as well. I’ve read so many different attempted academic explanations of her origins, but there’s no intellectual consensus about who she is. Did she emerge from Mictlan? Was she brought to us during the transatlantic slave trade? Does she have a West African origin? Was she brought to us from Europe? Nobody seems to have a definitive answer. I agree with theorists who propose that she is a complementary figure to la Virgen de Guadalupe. You’ve got two sides of that feminine divinity. You’ve got the life-giver and the life-taker, and both are necessary to reality. So she’s a dual mother figure; I find her foggy origins really striking and beautiful.

photo credit Geoff Cordner

I don’t pick up on fear or resistance in your description.

It’s not that I’m wholly unafraid of dying because, you know, there are forms of death I would rather avoid. But I do feel very blessed to have been raised with certain cultural practices that have taught me to relate to death in a way I don’t think is indicative of how the inhabitants of the global north largely relate to death. I have long thought of death personified. I’ve always gendered death in a hyper-feminine way. I’ve also always thought of her as kin, as somebody who you have to set a plate at the table for because she’s every sort of female kin figure wrapped into one. There is a Templo Santa Muerte on Melrose in LA that I go to. While I was working on Creep I made several visits to her templo and brought her tequila (laughs).

You have mentioned that you felt the presence of magic as you wrote this book. Would you speak more about this, about the presence of magic?

When I started working on Creep, I did so backwards. I started with the title essay, which is the final essay. The preceding work scaffolds the reader; once they arrive at the final essay they have what I hope is a very solid foundation to understand what’s taking place. When I started the process of working on that title essay, I immediately came to understand how painful the writing process would be for that piece, and perhaps for the entire book. I knew I was going to have to rely on methods that I hadn’t used before in order to be able to care for myself through the writing process. While I had therapeutic support at hand, in the form of a counselor whose expertise is in trauma, I knew that this was going to be nowhere near enough to sustain me. I started to attempt to determine what else I could use to sustain myself. And I came into magic, in that search. I began to make more and more explicit appeals to ancestral spirits. I did that in part because I started to write about those figures, about who they were when they were incarnate. And so I fused my practice of ancestor veneration with my writing practice–this was how I cultivated magic into the literary process.

How did the fusion between ancestor veneration and your writing practice take place?

One of the essays in the collection is titled “Mitote,” and it could be argued that the essay itself is an act of ancestor veneration because the essay is both a tribute and an anti-tribute to my maternal grandfather, Ricardo Serrano Rios. I felt moved to address him as a subject because his commitment to Mexican arts and letters inspired my interest and my love for that work. And I do believe that I inherited, in a sense, some of his skills. He claimed to have been the first publicist to operate in the city of Guadalajara, but because he’s a publicist, we don’t know if that’s true or not! So I think I inherited some of his knack for self-promotion. But at the same time, while I inherited these gifts from him, which are, in a sense, my heritage, my grandfather also rolled obstacles into the paths of girls and women–including girls and women who were his own family members. And I’m one of them. For example, my grandfather didn’t believe that I had the ability to write well because he was a misogynist and his misogyny prevented him from recognizing female literary capability, let alone female literary talent. And so “Mitote” is an attempt to reckon with that contradictory legacy.

All of us have ancestors with contradictory legacies. On one hand, that essay is very culturally specific but it is also simultaneously universal. I think so many women have these patriarchs who become ancestors who we struggle with. We have affection for them, but we also want to smack them because of the mixture of joy and pain they reigned on those around them. As I was working on that essay, I thought it would be interesting to appeal to my grandfather himself and invite him to participate in a literary and spiritual process of accountability by journeying with me through the drafting of this essay. So I made very specific and direct appeals to him. I have an ancestor altar in my home; I spent quite a bit of time at that altar making addresses to my grandfather, inviting him to participate, and asking him for his thoughts, for his ideas.

The way I invited him to message with me was as follows: my grandfather’s writing was published. He was not a prolific writer, and he wasn’t widely published, but he was published enough that I’ve been able to create a small collection of his work. One of the works I interacted with the most was an essay that he had drafted about his relationship to the writer Juan Rulfo. And ironically, the essay is less about Rulfo and more about my grandfather. So I made copies of these essays, cut them into strips, and then I issued questions. I would say to my grandfather: what are your thoughts on X, Y and Z? And I would use various techniques to invoke my grandfather’s spirit–incenses, oils, herbs, roots. Then I would stand on my balcony, drop the strips of paper on the ground, collect them in a set order, and read them to myself–that would be his response to me. It was up to me to interpret what he was returning to me, as I developed this method of interacting with him.

photo credit Geoff Cordner

You have said that: “Catharsis does not belong to the artist. Catharsis is a gift that the artist gives to her audience.” And you have also said that the work of art is separate from the conditions in which the work of art is created. Would you speak about this distinction, and also about what your own space of catharsis is?

I have not been asked that question before and I love it. I began to think about the preoccupation with catharsis when my memoir Mean was published and I so frequently was asked if authoring it had provided me with some sort of catharsis. I felt as if those who asked me that question were positioning me as a human vessel. As if art was a spigot I could attach to myself, and then through that art spigot, I could simply empty the pain that resided in me into this receptacle and give it to an audience. And that’s such a hyper-simplification of what it is to make art and also what it is to experience art as its audience. I think the origin of this preoccupation has its roots in the rise of self-help culture in the United States. There’s this belief that the artist is engaged in the work of self-help through creation, which is so odd to me because the notion of art preceded the development of the self. Art has historically been a collective project; art has not largely been a project of selfhood. I wanted to confront that in my work and I wanted my readers and anybody who’s interested in my work to understand what my explicit art-making conditions have been in order to silence that line of questioning. And it’s worked pretty effectively. I haven’t gotten that question anymore. I was once being interviewed about Mean by somebody who knew very little about the crisis of global femicide. At the end of the interview, the interviewer asked me: “Well, what do we do to solve the problem?” And I just thought to myself: “How unserious are you?” Also, it’s not the artist’s responsibility per se to lead organizing and to lead activism. We can have a hand in it, but that’s not necessarily the chief job of the artist. For me, if I do want to experience catharsis, which I do regularly, it tends to happen when I am engaged with beauty, not when I’m engaged in art-making. I live near the San Gabriel Mountains, and I tend to go on very long, meandering walks and hikes. There will be moments that I can only describe as steeped in mysticism, where I am with the earth and with the flora and with the fauna, and we are all acknowledging one another. And in that moment, I experience what I think could appropriately be called some sort of catharsis. It also happens to me when I’m interacting with and caring for plants. Catharsis is achieved for me through laughter. And I laugh all day, every day. So these are the domains where catharsis is accessible to me. And by being an audience to others’ art.

In the essay “Slimed” you write: “sometimes laughter anchors us. It’s the best way of reminding ourselves that we are alive.” What makes you laugh?

Oh my goodness, I love laughing. I think my laugh is actually more of a cackle. My laugh is so loud that when I used to teach high school, sometimes the teachers in my hallway would shut their doors so that they wouldn’t have to hear my shit. But so many things make me laugh. I am a big fan of puns. I love absurd animal videos. There’s a viral video of a possum that ran on onto a football field and got dragged off the field, and has this look on his face like he’s saying “noooo!” And everyone in the comment section is like, “let him play!” I love surreal humor, and then if you can mix the surreal with wordplay, I’m on cloud nine. I also really like very high femme bitchy humor. For example, the quips and backhanded insults that are issued on the Real Housewives. There’s this episode of the Real Housewives of New York where Aviva Drescher is sitting at the table and says: “the only fake thing about me is my leg,” and she rips off her prosthesis and throws it. I almost died. I think all the viewers almost died. Nobody knows what to do because there’s no social script for a socialite tossing her leg in the middle of high tea. So those are the sorts of things that inspire my laughter. My dream is to one day write about the Real Housewives.

Where do you go to find hope?

I am inspired and made hopeful by young people all day, every day. I’m not teaching at the moment, but I hope to be teaching again in the future. And every day spent with students, especially eager and hopeful students, returns hope to me. Activist spaces inspire and give me hope. I also engage in certain spiritual practices that renew my hope on a daily basis.

What is some of the most important advice you have ever received?

Writers will sometimes ask me about the pitfalls of engaging in confessional work. They’ll ask me about the courage that is needed to write personal narrative, personal history, personal essays. They’ll ask what my fears are as they relate to alienating loved ones or others who might be offended or perceive harm as a result of writing about them. And what I have come to realize–and this is by observing writers and others that I admire–is that doing that work requires one to be very principled. If one experiences a call to tell a particular story, to document a narrative, to draft certain prose, and one feels that the compulsion behind that is motivated by justice, and there’s a sense that there’s going to be incredible risk, it’s okay to take that risk. It’s necessary to take that risk. Risk comes with the territory. And if I alienate my entire audience I can live with that because I’ve abided by my conscience. It is important to remember that we’re not necessarily artists because we’re trying to make friends. It’s like, since when is art a friend-making project? If you want friends, join a club! There are a lot of clubs and they probably want you. But like, don’t write a book (laughs).

You have talked about thinking of oneself as a future ancestor. As a future ancestor, how would you like to be remembered?

I would love to be recalled as a passionate, loud and impish cheerleader for all forms of justice. And, impishness implies that there could be some mischief, there could be some cleverness, we can make this fun. Social justice doesn’t have to be dour. We can take the oppressor’s keys and hide them. And I would hope that I could inspire this behavior from beyond the grave, from the afterlife.

photo credit Geoff Cordner

Creep is available for purchase here.

We can take the oppressor’s keys and hide them

In Conversation with Myriam Gurba

Billy Lezra

photo credit Geoff Cordner

Myriam Gurba is a writer and artist. She is the author of the true crime memoir Mean, a New York Times Editors’ Choice. O, The Oprah Magazine, ranked Mean as one of the best LGBTQ books of all time. Publishers Weekly describes Gurba as having a voice like no other. Her essays and criticism have appeared in The Paris Review, Time, and 4Columns.

Creep is Gurba’s informal sociology of creeps, a deep dive into the dark recesses of the toxic traditions that plague the United States and create the abusers who haunt our books, schools, and homes. Through cultural criticism disguised as personal essay, Gurba studies the ways in which oppression is collectively enacted, sustaining ecosystems that unfairly distribute suffering and premature death to our most vulnerable. Yet identifying individual creeps, creepy social groups, and creepy cultures is only half of this book’s project—the other half is examining how we as individuals, communities, and institutions can challenge creeps and rid ourselves of the fog that seeks to blind us.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

One of the throughlines I noticed as I was reading Creep is the rigorous act of naming–the process of identifying institutional creepdom, intimate partner violence, femicide, misogyny. How did you reach the point where you were prepared to engage in naming?

There have been various extended episodes in my life that have increasingly radicalized me. Disclosing to a former employer that I had experienced domestic violence and then being gaslit by that employer was very radicalizing and underscored my responsibility to tell the truth about my experiences. It underscored the importance of language and the importance of naming. In the “Creep” essay, the title essay, I describe both my entrapment and my escape. Language and naming were critical to my liberation. On the night that I escaped from my abuser, I fled to a friend’s home. That friend was outside the house, physically blocking my abuser from chasing me into the home. I could hear the argument that was happening outdoors: at one point my defender yelled at my abuser, “Get the fuck out of here, you are a creep.” I had not heard anybody confront my abuser, let alone appropriately name him. When I heard him appropriately labeled, appropriately categorized so loudly, because the word rang into the night, the word “creep” broke my abuser’s spell because now he was unmasked, and it was language that had done the unmasking. That evening I understood that this word could function as a verbal talisman for me. And so I grabbed onto it and used it like a torch to illuminate my way as I was writing the book.

The naming breaks the fog.

Exactly.

The image of the fog seeps through Creep. How did you land on that image?

When I set out to write the title essay, I knew that it was going to have Gothic and horror elements. I thought the essay could be an exercise in horror nonfiction, so I borrowed a lot of horror tropes and devices that take the reader to this terrified precipice. I thought quite a bit about different devices that I would introduce in order to communicate the unique horror that is intimate partner violence, because ultimately romance is used to ensnare the victim. I also wanted my starting point for that essay to be my girlhood, not the abusive relationship itself. I wanted the reader to understand that every femicide I encountered has cast a shadow across my life. Once I arrived on the precipice of becoming a victim of femicide myself, I understood that the death threats that were being issued to me were quite real, and that they were credible. All my life, women had been murdered as a result of misogyny, and I had been either a direct or indirect witness to this, which is why I include all these female figures. I’m attempting to demonstrate that, from childhood, this is something I was primed to fear, and that, in a sense, all women who learn of these femicides across our lifespans are being primed to fear them–it’s collective. So I was thinking: how can I communicate that romance is one of these weapons? Because romance is typified as soft, as caressing, as intimate, as vulnerable, as velvety. So I decided to locate the beginning of that narrative during my girlhood; my girlhood was also a time that was shrouded in fog because of where I grew up geographically. The fog was this terrifyingly soft entity that could kill people–I lost people to accidents that happened in the fog because we trusted that we knew the geography that was contained within it, because we were locals, we knew these roads. And what I’m trying to express is that you don’t know who else you’re sharing these roads with because you can’t even see your own hand, let alone your fellow traveler. So I fused that terrifying entity, that marine layer, with this notion of intimate partner violence.

Another image I noticed is the navaja, the blade, the scalpel, the knife. How this sharpness contrasts against the softness of the fog.

The image of the knife and the fascination with the knife came to me through Lorena Gallo and my interest in her. During the 1990s she became a household name; her ordeal was widely misrepresented by U.S. and international media. She was a Latin American immigrant, like my mother. I was very struck by some of the physical similarities she had to my mother. Rarely did I see, and in particular hear, women who sounded like my mother on TV. And so here’s this woman who mirrors my mother, who is testifying that she is a victim of really heinous, intimate partner violence–that her husband had raped her and that she had defended herself by essentially destroying the weapon that he was using, which was his penis. This story was so fascinating to me because I had never heard of such a thing–so many of us had never heard of such a thing. Now, as a person who is a fellow survivor and somebody who advocates on behalf of survivors, I understand that women who take action like Lorena Gallo are disproportionately punished for doing so. We’re disproportionately overrepresented in jails and prisons.

I found Lorena Gallo to be so interesting because she did not receive the standard punishment, which is incarceration. And that’s what I want for all women who engage in self-defense–I want us to be able to use the defense of violence and to be honored as women who have selves worthy of defending. This was extended to Lorena Gallo but is not extended to so many. And that’s my specific reason for invoking her. I wanted to write about her as a potential folk hero for women who are experiencing similar savagery. I wanted to propose not just a shield, but a sword, in the form of Santa Lorena.

You write: “My devotion to la Santa Muerte is why I keep a talisman of her skeletal shape close to my pillow.” Would you speak more about this devotion?

For a long time, I was a little frightened of Santa Muerte. The press has done a fantastic job of stigmatizing her and of framing her as a narco folk saint. She sits on the pantheon alongside Malverde. She has an enormous cult following of women, in particular women who appeal to her as a romantic intercessor. She also has a great deal of appeal among those of us who have been exiled from the Catholic Church. Queer and trans folk also venerate her because Santa Muerte welcomes everybody; none of us are going to escape her kiss.There’s nobody who’s going to sit on her sidelines–we’re all getting on this train. And so in that sense, she’s wonderfully democratic. Once I began to understand her in that way, I began to experiment with venerating her and became quite comfortable doing so. Then I came to realize that perhaps I’ve been on a trajectory my entire life that has been calling me toward her because I was a teenage goth! I just didn’t know what shrine I was on my way to. And now I know. I’m no longer afraid of her, and I make appeals to her. I find her so compelling and so interesting because her origins are so foggy as well. I’ve read so many different attempted academic explanations of her origins, but there’s no intellectual consensus about who she is. Did she emerge from Mictlan? Was she brought to us during the transatlantic slave trade? Does she have a West African origin? Was she brought to us from Europe? Nobody seems to have a definitive answer. I agree with theorists who propose that she is a complementary figure to la Virgen de Guadalupe. You’ve got two sides of that feminine divinity. You’ve got the life-giver and the life-taker, and both are necessary to reality. So she’s a dual mother figure; I find her foggy origins really striking and beautiful.

photo credit Geoff Cordner

I don’t pick up on fear or resistance in your description.

It’s not that I’m wholly unafraid of dying because, you know, there are forms of death I would rather avoid. But I do feel very blessed to have been raised with certain cultural practices that have taught me to relate to death in a way I don’t think is indicative of how the inhabitants of the global north largely relate to death. I have long thought of death personified. I’ve always gendered death in a hyper-feminine way. I’ve also always thought of her as kin, as somebody who you have to set a plate at the table for because she’s every sort of female kin figure wrapped into one. There is a Templo Santa Muerte on Melrose in LA that I go to. While I was working on Creep I made several visits to her templo and brought her tequila (laughs).

You have mentioned that you felt the presence of magic as you wrote this book. Would you speak more about this, about the presence of magic?

When I started working on Creep, I did so backwards. I started with the title essay, which is the final essay. The preceding work scaffolds the reader; once they arrive at the final essay they have what I hope is a very solid foundation to understand what’s taking place. When I started the process of working on that title essay, I immediately came to understand how painful the writing process would be for that piece, and perhaps for the entire book. I knew I was going to have to rely on methods that I hadn’t used before in order to be able to care for myself through the writing process. While I had therapeutic support at hand, in the form of a counselor whose expertise is in trauma, I knew that this was going to be nowhere near enough to sustain me. I started to attempt to determine what else I could use to sustain myself. And I came into magic, in that search. I began to make more and more explicit appeals to ancestral spirits. I did that in part because I started to write about those figures, about who they were when they were incarnate. And so I fused my practice of ancestor veneration with my writing practice–this was how I cultivated magic into the literary process.

How did the fusion between ancestor veneration and your writing practice take place?

One of the essays in the collection is titled “Mitote,” and it could be argued that the essay itself is an act of ancestor veneration because the essay is both a tribute and an anti-tribute to my maternal grandfather, Ricardo Serrano Rios. I felt moved to address him as a subject because his commitment to Mexican arts and letters inspired my interest and my love for that work. And I do believe that I inherited, in a sense, some of his skills. He claimed to have been the first publicist to operate in the city of Guadalajara, but because he’s a publicist, we don’t know if that’s true or not! So I think I inherited some of his knack for self-promotion. But at the same time, while I inherited these gifts from him, which are, in a sense, my heritage, my grandfather also rolled obstacles into the paths of girls and women–including girls and women who were his own family members. And I’m one of them. For example, my grandfather didn’t believe that I had the ability to write well because he was a misogynist and his misogyny prevented him from recognizing female literary capability, let alone female literary talent. And so “Mitote” is an attempt to reckon with that contradictory legacy.

All of us have ancestors with contradictory legacies. On one hand, that essay is very culturally specific but it is also simultaneously universal. I think so many women have these patriarchs who become ancestors who we struggle with. We have affection for them, but we also want to smack them because of the mixture of joy and pain they reigned on those around them. As I was working on that essay, I thought it would be interesting to appeal to my grandfather himself and invite him to participate in a literary and spiritual process of accountability by journeying with me through the drafting of this essay. So I made very specific and direct appeals to him. I have an ancestor altar in my home; I spent quite a bit of time at that altar making addresses to my grandfather, inviting him to participate, and asking him for his thoughts, for his ideas.

The way I invited him to message with me was as follows: my grandfather’s writing was published. He was not a prolific writer, and he wasn’t widely published, but he was published enough that I’ve been able to create a small collection of his work. One of the works I interacted with the most was an essay that he had drafted about his relationship to the writer Juan Rulfo. And ironically, the essay is less about Rulfo and more about my grandfather. So I made copies of these essays, cut them into strips, and then I issued questions. I would say to my grandfather: what are your thoughts on X, Y and Z? And I would use various techniques to invoke my grandfather’s spirit–incenses, oils, herbs, roots. Then I would stand on my balcony, drop the strips of paper on the ground, collect them in a set order, and read them to myself–that would be his response to me. It was up to me to interpret what he was returning to me, as I developed this method of interacting with him.

photo credit Geoff Cordner

You have said that: “Catharsis does not belong to the artist. Catharsis is a gift that the artist gives to her audience.” And you have also said that the work of art is separate from the conditions in which the work of art is created. Would you speak about this distinction, and also about what your own space of catharsis is?

I have not been asked that question before and I love it. I began to think about the preoccupation with catharsis when my memoir Mean was published and I so frequently was asked if authoring it had provided me with some sort of catharsis. I felt as if those who asked me that question were positioning me as a human vessel. As if art was a spigot I could attach to myself, and then through that art spigot, I could simply empty the pain that resided in me into this receptacle and give it to an audience. And that’s such a hyper-simplification of what it is to make art and also what it is to experience art as its audience. I think the origin of this preoccupation has its roots in the rise of self-help culture in the United States. There’s this belief that the artist is engaged in the work of self-help through creation, which is so odd to me because the notion of art preceded the development of the self. Art has historically been a collective project; art has not largely been a project of selfhood. I wanted to confront that in my work and I wanted my readers and anybody who’s interested in my work to understand what my explicit art-making conditions have been in order to silence that line of questioning. And it’s worked pretty effectively. I haven’t gotten that question anymore. I was once being interviewed about Mean by somebody who knew very little about the crisis of global femicide. At the end of the interview, the interviewer asked me: “Well, what do we do to solve the problem?” And I just thought to myself: “How unserious are you?” Also, it’s not the artist’s responsibility per se to lead organizing and to lead activism. We can have a hand in it, but that’s not necessarily the chief job of the artist. For me, if I do want to experience catharsis, which I do regularly, it tends to happen when I am engaged with beauty, not when I’m engaged in art-making. I live near the San Gabriel Mountains, and I tend to go on very long, meandering walks and hikes. There will be moments that I can only describe as steeped in mysticism, where I am with the earth and with the flora and with the fauna, and we are all acknowledging one another. And in that moment, I experience what I think could appropriately be called some sort of catharsis. It also happens to me when I’m interacting with and caring for plants. Catharsis is achieved for me through laughter. And I laugh all day, every day. So these are the domains where catharsis is accessible to me. And by being an audience to others’ art.

In the essay “Slimed” you write: “sometimes laughter anchors us. It’s the best way of reminding ourselves that we are alive.” What makes you laugh?

Oh my goodness, I love laughing. I think my laugh is actually more of a cackle. My laugh is so loud that when I used to teach high school, sometimes the teachers in my hallway would shut their doors so that they wouldn’t have to hear my shit. But so many things make me laugh. I am a big fan of puns. I love absurd animal videos. There’s a viral video of a possum that ran on onto a football field and got dragged off the field, and has this look on his face like he’s saying “noooo!” And everyone in the comment section is like, “let him play!” I love surreal humor, and then if you can mix the surreal with wordplay, I’m on cloud nine. I also really like very high femme bitchy humor. For example, the quips and backhanded insults that are issued on the Real Housewives. There’s this episode of the Real Housewives of New York where Aviva Drescher is sitting at the table and says: “the only fake thing about me is my leg,” and she rips off her prosthesis and throws it. I almost died. I think all the viewers almost died. Nobody knows what to do because there’s no social script for a socialite tossing her leg in the middle of high tea. So those are the sorts of things that inspire my laughter. My dream is to one day write about the Real Housewives.

Where do you go to find hope?

I am inspired and made hopeful by young people all day, every day. I’m not teaching at the moment, but I hope to be teaching again in the future. And every day spent with students, especially eager and hopeful students, returns hope to me. Activist spaces inspire and give me hope. I also engage in certain spiritual practices that renew my hope on a daily basis.

What is some of the most important advice you have ever received?

Writers will sometimes ask me about the pitfalls of engaging in confessional work. They’ll ask me about the courage that is needed to write personal narrative, personal history, personal essays. They’ll ask what my fears are as they relate to alienating loved ones or others who might be offended or perceive harm as a result of writing about them. And what I have come to realize–and this is by observing writers and others that I admire–is that doing that work requires one to be very principled. If one experiences a call to tell a particular story, to document a narrative, to draft certain prose, and one feels that the compulsion behind that is motivated by justice, and there’s a sense that there’s going to be incredible risk, it’s okay to take that risk. It’s necessary to take that risk. Risk comes with the territory. And if I alienate my entire audience I can live with that because I’ve abided by my conscience. It is important to remember that we’re not necessarily artists because we’re trying to make friends. It’s like, since when is art a friend-making project? If you want friends, join a club! There are a lot of clubs and they probably want you. But like, don’t write a book (laughs).

You have talked about thinking of oneself as a future ancestor. As a future ancestor, how would you like to be remembered?

I would love to be recalled as a passionate, loud and impish cheerleader for all forms of justice. And, impishness implies that there could be some mischief, there could be some cleverness, we can make this fun. Social justice doesn’t have to be dour. We can take the oppressors’ keys and hide them. And I would hope that I could inspire this behavior from beyond the grave, from the afterlife.

photo credit Geoff Cordner