Artists acknowledge the moments of transformation

In Conversation with Raquel Gutiérrez

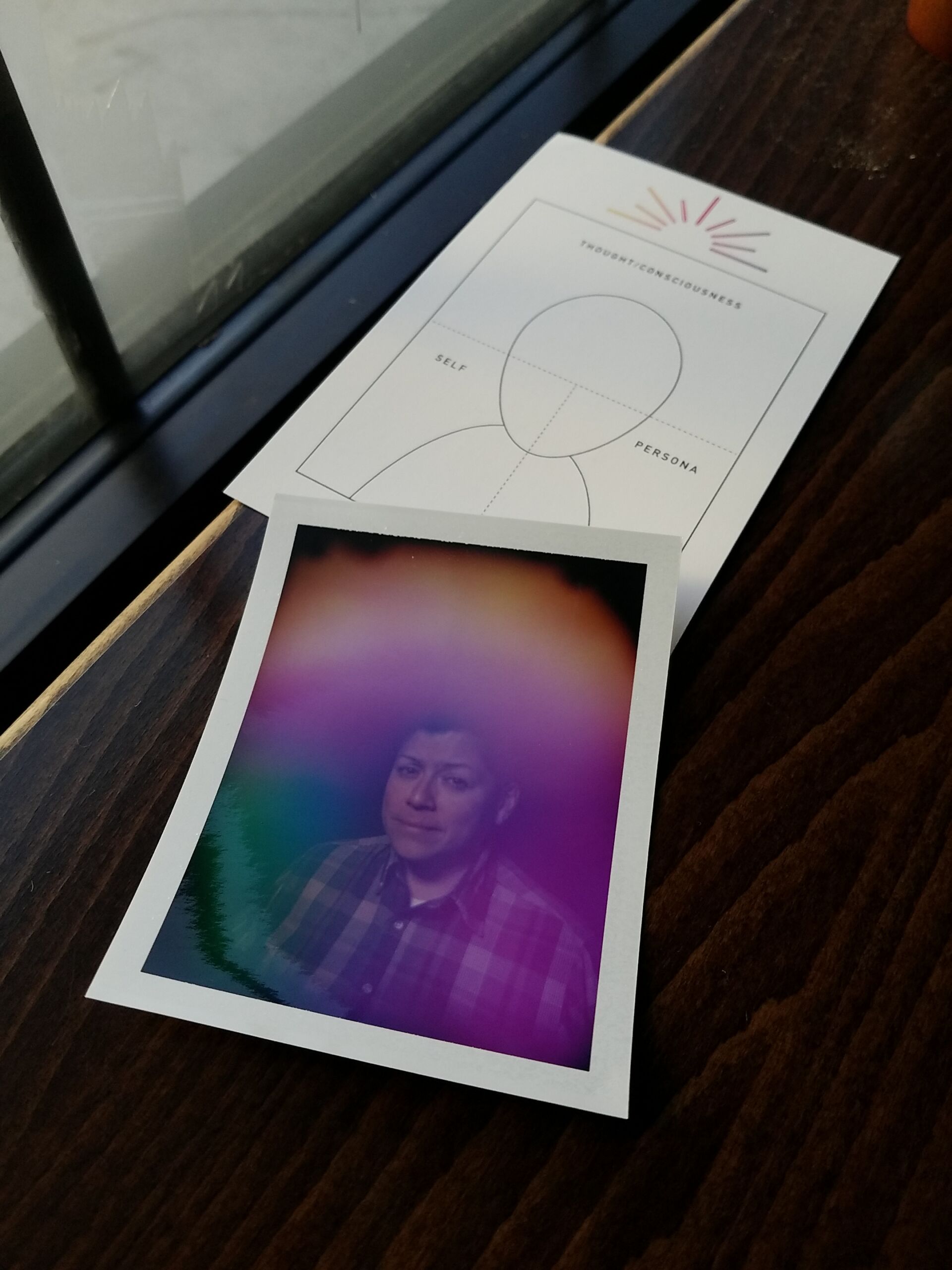

Billy Lezra

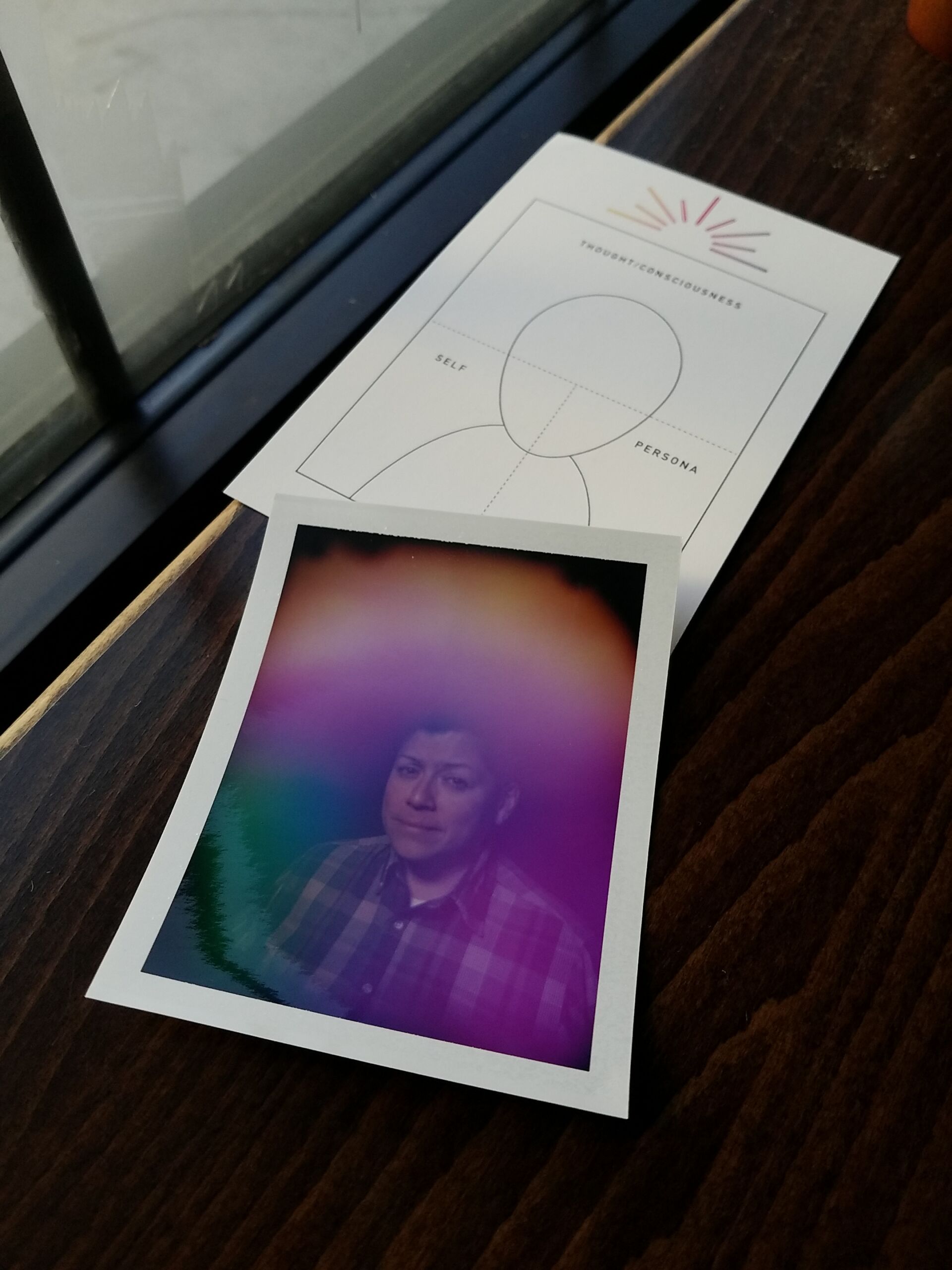

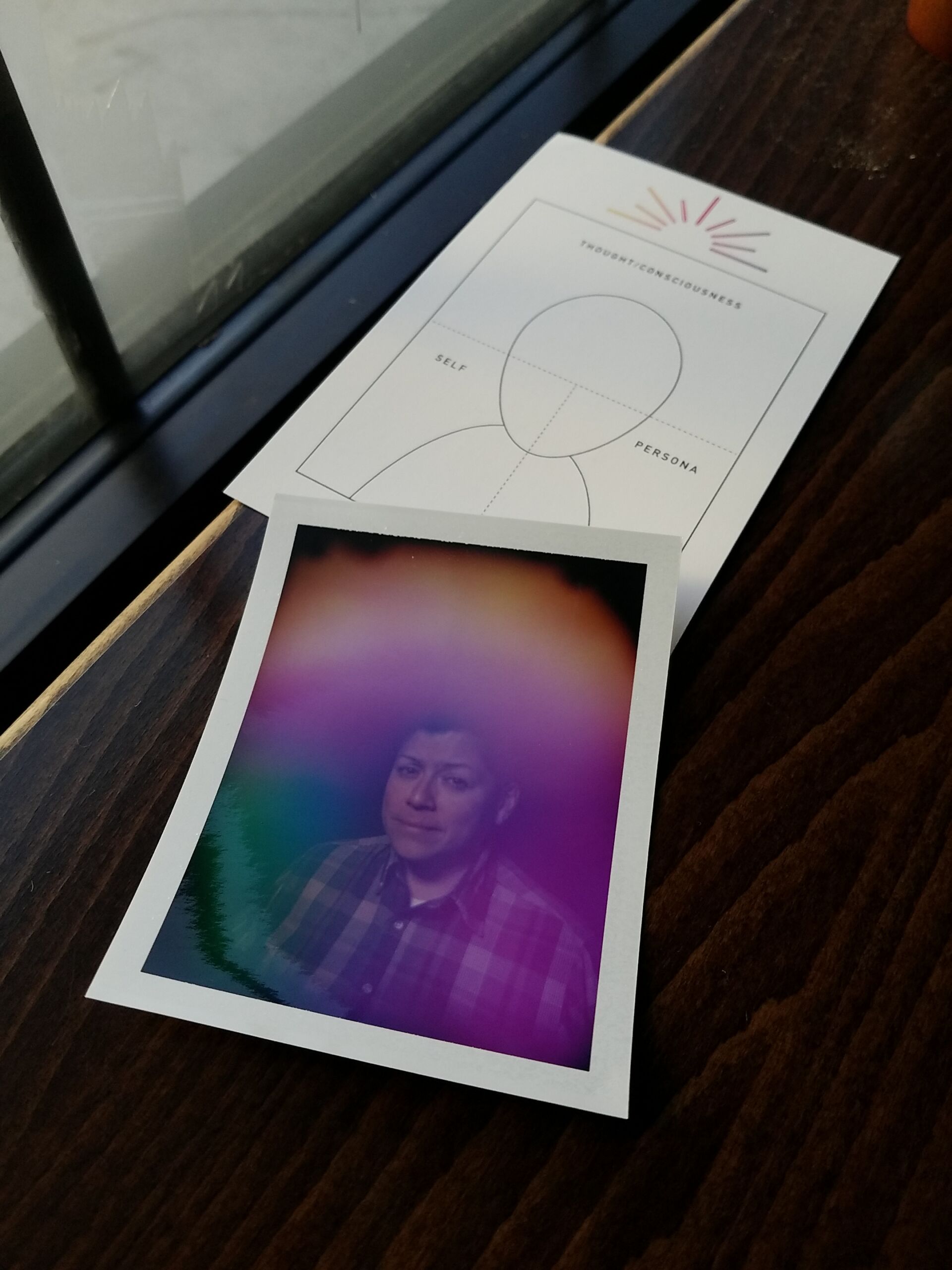

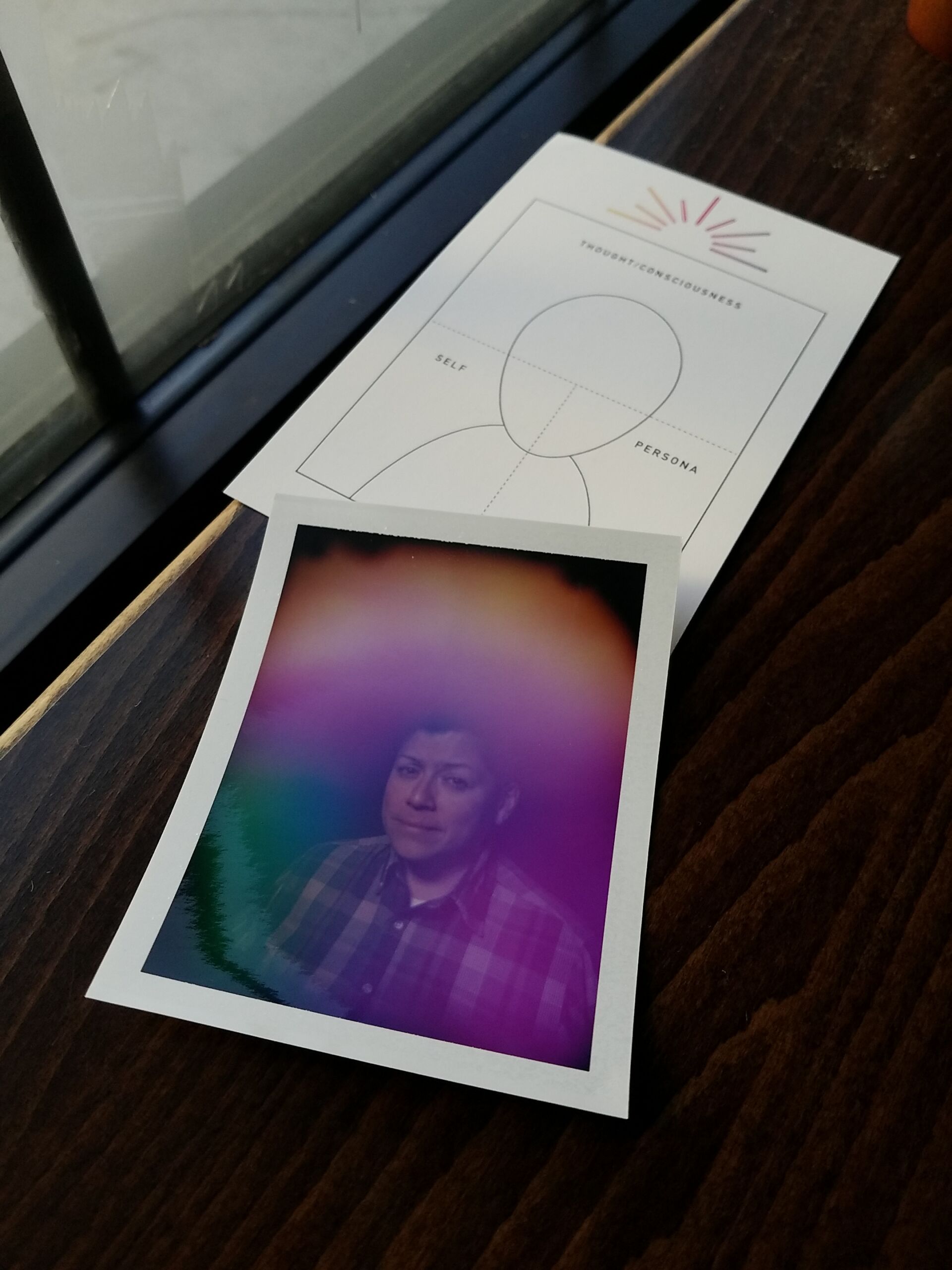

photo credit: Thea Quiray Tagle

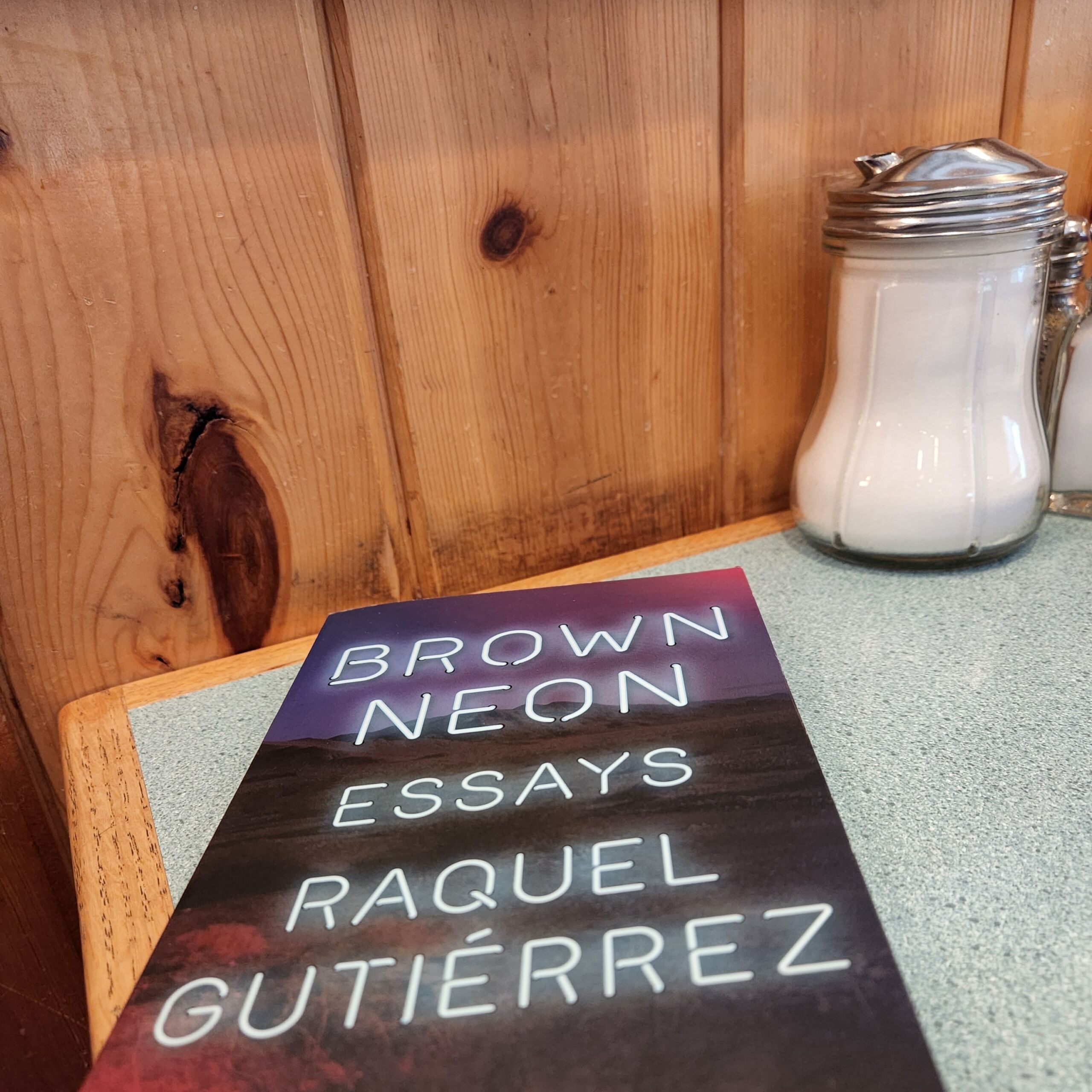

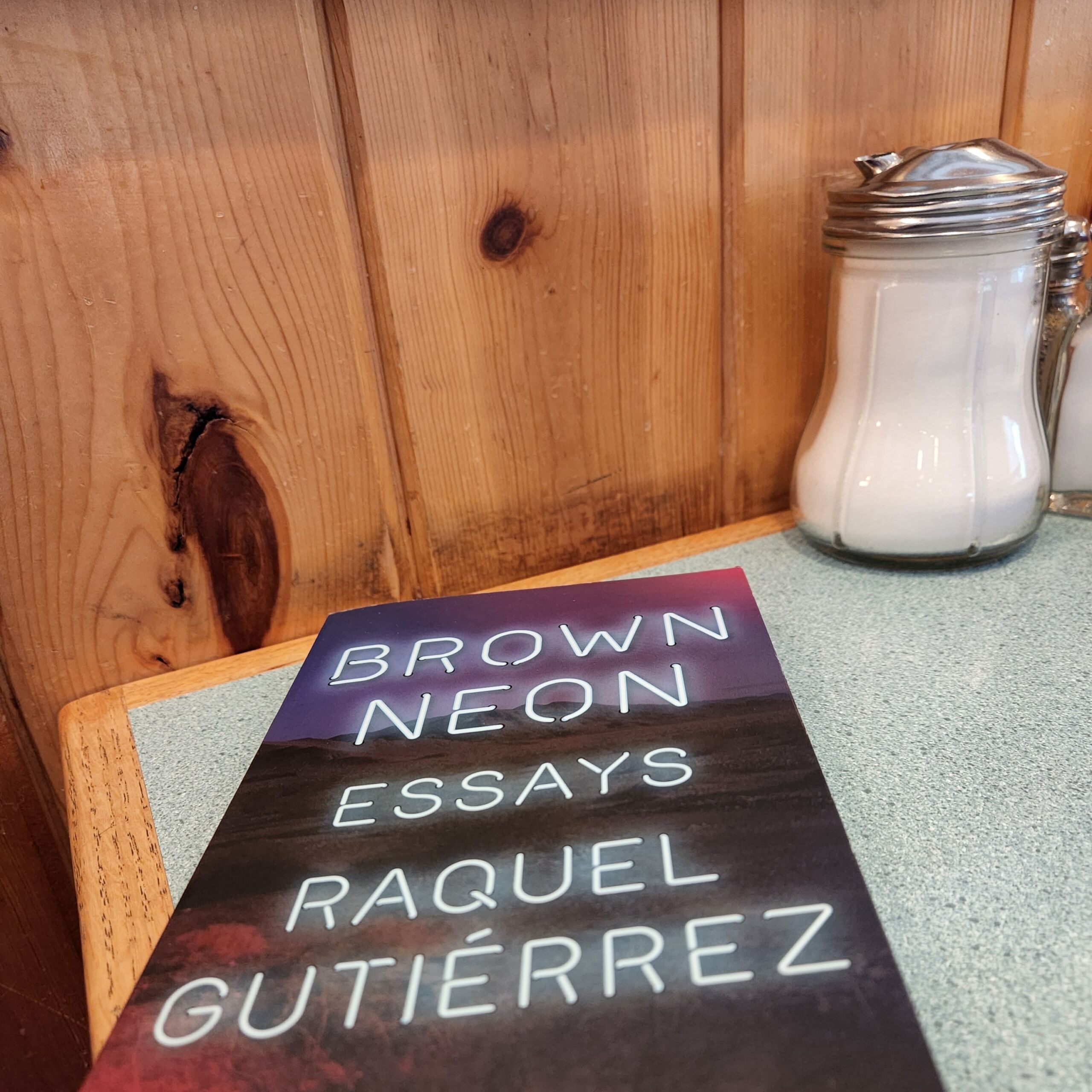

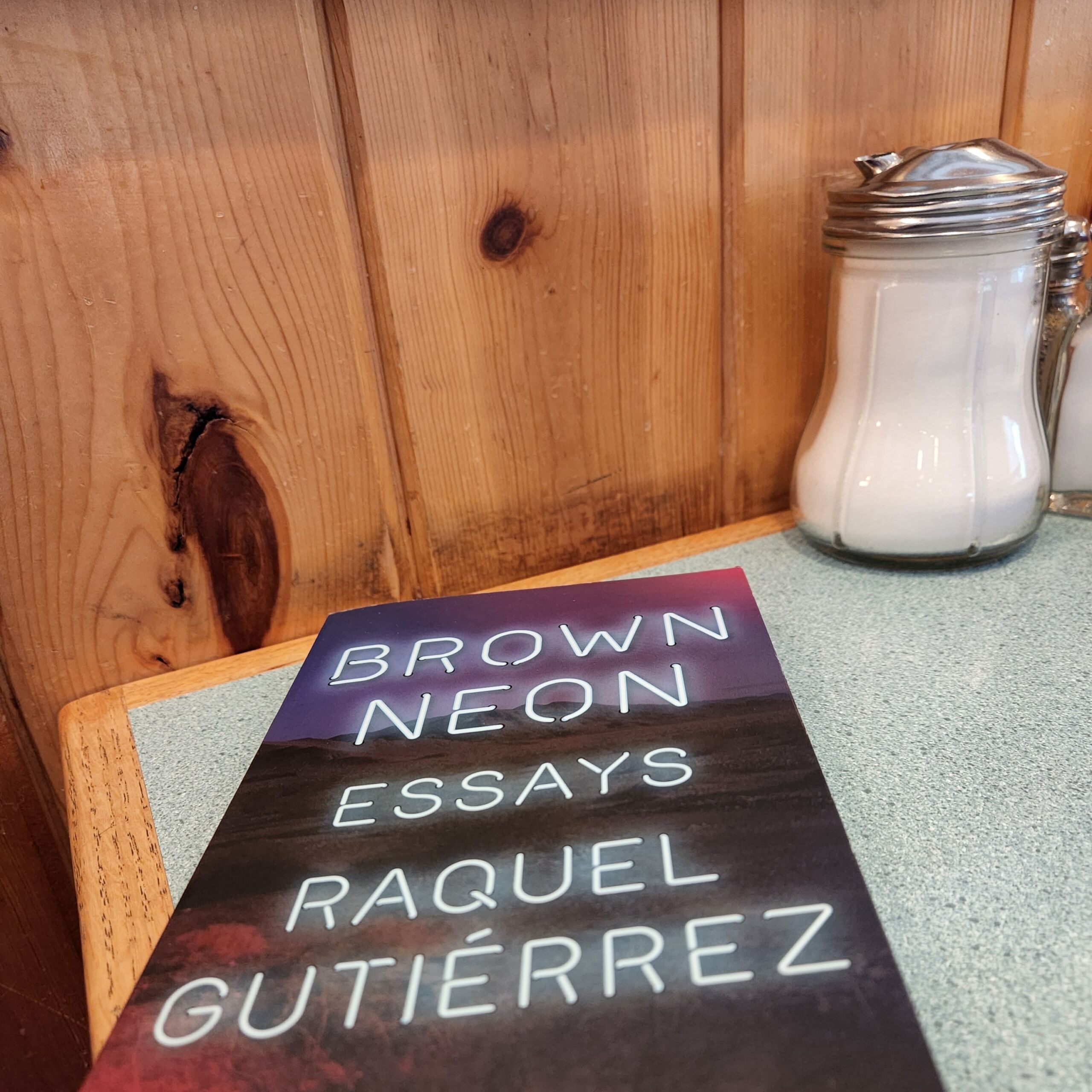

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Raquel Gutiérrez is a critic, essayist, poet, performer, and educator. Gutiérrez’s first book Brown Neon (Coffee House Press) was named as one of the best books of 2022 by The New Yorker and listed in The Best Art Books of 2022 by Hyperallergic. Brown Neon was a Finalist for the Lambda Literary Prize for Best Lesbian Biography/Memoir, a Finalist for the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses’ Firework Award in Creative Nonfiction and Recipient of The Publishing Triangle Judy Grahn Award for Lesbian Nonfiction. A 2021 recipient of the Rabkin Prize in Arts Journalism, as well as a 2017 recipient of The Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant, Gutiérrez teaches in the Oregon State University-Cascades Low Residency Creative Writing MFA Program, as well as for The Institute of American Indian Arts’s (IAIA) Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing program. Gutiérrez gets to call Tucson, Arizona home.

Follow Raquel on Twitter.

In Brown Neon you write: “You need a lot to make a stable foundation, to build walls capable of holding difficult truths.” Although this line is in reference to making adobe, it reminded me of the act of writing. As you write, how do you go about building walls capable of holding difficult truths?

That’s a really powerful question. It’s one thing to write and then there’s another element of writing that involves meaning-making and co-authoring meaning with your reader. So writing is always this process, this act of faith. When you write something, you’re having a conversation with an imagined reader, and then that conversation gets corroborated by your editor, who is a much-needed guard at the post of legibility and comprehension. So once the work passes the editor and reaches the reader’s hands, you hope that you’re able to meet the reader where the reader is at, and that the reader is able to meet you where you’re at. When it comes to building walls, a foundation, you’re creating something that you can back up with a sense of your imagination, the imaginary, your lineages and influences, your vantage point, and the way in which the culture conditions your experience of it. You just write with hopes that you’re able to communicate these threads around culture and politics and the lyric, which all come together to maybe help launch someone into activation. I always struggle with this idea of, “Is it interesting?” But then I’m like, “Well, who’s my imagined audience?” or “Who’s my imagined chorus of disapproval?” And it’s always somebody situated in some sort of coastal metropole. And I’m just like, “Oh, well, no, we’re just going to have to challenge them and hope that they allow themselves to stretch.” I guess the stability of building these walls comes from finding an unshakable sense of self and purpose because it’s so easy to just stop writing.

What qualities does your ideal editor have?

My ideal editor has a light touch, a breadth of understanding, and a diversity of context. They are someone who has read outside of the established canons, someone who’s just like: “I’ve never read that before. I’ve never seen that before on the page,” but trusts the innovative impulse.

In Brown Neon you reference the Anzaldúan concept of nepantla– “the space in between, the locus and sign of transition, the place/space where realities interact and imaginative shifts happen.” When did you first start exploring this space?

Since birth. Since I stepped out of my parents’ house into a public space and realized that what happens in the domestic space is at odds with what happens in these shared collective public spaces that are governed by laws that seem to just stop at your doorstep. When you’re a child of immigrants and you’re brought or born into a new context, you’re a witness to the tensions and struggles and bureaucratic violences the governing figures in your life are dealing with. I think taking that into account at a very fundamental level is how I’ve been introduced to these dialectical moments of like, “Oh, these are two entities with varying power differentials encountering one another.” And that encounter produces a thing, a change. And these power differentials come and go, depending on where you’re at and who’s in the room with you. And so once you step out into the world on your own, you experience authority figures in different ways. There’s a constant flux: nothing is really fixed.

Would you speak about the presence of intertextuality in your work?

The intertextual impulse in my book has always been present in the sense that when you’re writing, you always have other writers’ voices in your head. You’re always moved by somebody else’s language in your mind, in your mouth, until you’re able to find the language for yourself. Someone’s providing you with language, especially if you’re writing about yourself or writing about whatever cultural quandaries and entanglements you’re a part of or adjacent to. You’re always writing from a prism that is refracting the other cultural artifacts that stayed on you or with you in your energetic field. So in a sense, intertextuality is getting these cues for how to live on your terms of engagement. And as you mature as a writer, you’re like, “Okay, let me just turn the volume down on that so that I can focus on turning the volume up on my own voice and hear how I would craft my own syntax.”

What was the process of taking these stand-alone essays and turning them into a book-length project?

When you’re writing for whatever range of platforms that appeal to your aesthetics, politics, and political commitments, you’re adhering to the creative editorial mandates of the magazine or publication. As I was writing my essays, I realized that there were connections and threads that served as connective tissue for a book project, a book-reading experience. So then I started writing for that experience. It’s kind of like putting on a curatorial hat, and thinking about the experience you want the reader to have when they come and spend their precious time with you. You’re offering anywhere between 7 to 15 hours on a text, and you want to give the reader a cohesive experience, a trip, a journey, a beginning to an end. I started with the end of a mentor’s life–death is this powerful occasion for unmooring. My mentor’s death marked the end of my relationship with her in her living embodiment, and the end of my relationship with Southern California. So I took that grief and animated my experience of living in the desert, trying to find community, making sense of heartbreak, mourning, loss, and starting this new life. And then I explored what the desert offered and meant on a literary level, an artistic level, on a queer level. So I just took my chisel and chipped away at this slab of marble until La Pietà revealed itself to me, my own La Pietà.

How do you know when a piece of work is finished?

I know that it’s finished if I feel okay enough with it, and it meets the deadline. Maybe one day I will have the luxury of time and just be like, “Oh my God, I’m so glad I waited those extra three months for that final brushstroke, that final flourish because it came when it came.” I wish I had to worry less about making ends meet and just be able to focus on syntax, on just getting better. I wish I had more time.

Would you speak about the relationship between being in community and being an artist?

I think we’re drawn to community because we have a set of values that we either are familiar with, we know about, we’ve consciously chosen, or maybe that we’re resistant to. Maybe family is a value that you have, but you’re a radical queer, and you’re just like, “No, family is not a value for me.” And you find ways to contradict or corroborate this value through the choices you make in the communities that you decide you want to be a part of, or drive by, drive through, flirt with, consider. So community is there, I think, to help you test drive your values.

You write this question: “Was I destined to enact my own chaos that comes with the territory of being an artist?” I was intrigued by the use of the word chaos–in the Greek etymology chaos is defined as the abyss or emptiness that existed before things came into being. For you, what is the relationship between being an artist and approaching the abyss?

I appreciate you going into that etymologically–the abyss and the unpredictability of chaos. Most people in my position would have gone into engineering, medicine, the stability careers. I went back to school late. Had I gone to college right out of high school, I would have just barely made it. My tuition would have been okay, I wouldn’t have needed to take out loans. But the way that predatory lending played out made it impossible to imagine the promise of “Hey, you go to school, you get your degree, you’ll get a good entry-level job” and all of the things that come with natural ascension in the workforce. All of that is an abyss. That’s chaos. That was unpredictable. I went in there thinking I was going to be a middle manager of this nonprofit organization and be making at least 60K in 2002. And that didn’t happen. So economics demanded something else from a college-educated workforce. When you give me chaos on a platter, that’s kind of where my mind goes; the chaos of trying to eke out a life from some sort of creative field was challenging and hard and sad and heartbreaking because there comes a point where you can’t be too creative.

In an interview you said: “There are many approaches to pain. Are you in it? Are you beside it? Are you with it? I think the prepositional dynamic is an interesting mode of entry into your pain because it just makes you slow down with it.” What is the relationship between writing, the process of documenting, and pain?

The occasion that makes people sit down and bang out a draft of a manuscript is often grief. When you lose someone very close to you, which is the classic example of grief–losing your dad or mom or your partner or your animal friend–there’s a spiritual pain that comes from the finality of their absence and the fact that you’ll never see them again in their human or material form. That’s a really hard fact of life, and it shows you what you’re made of. And a lot of people are able to come to the other side of it, but a lot of people are not. A lot of people self-medicate or enact suicide in small increments in the sense that you’re just like, “Well, I’m going to keep hurting myself today.” I think the reason we need artists and writers so badly is because they’re able to provide us with some language for mourning beautifully, some language for mourning simply, some language for mourning immediately, some relief. That’s the Mount Everest artists and writers are scaling for people who are unable to do that for themselves. A lot of people don’t know how to make language. When I teach an introduction to poetry class, I always try to coax students to think about, like, “Hey, one day you’re going to have to make a toast at a wedding. One day you’re going to have to write a eulogy at a funeral. One day a baby is going to come into your family’s life and it would be nice to have some language ready for these arrivals and departures.” I think poets and artists are there to acknowledge the moment of transformation. This is why we have dirges. This is why we have elegies. This is why we have ballads, sonnets. Somebody inspired this. And pain is something we can gather around for, if we are lucky.

Where do you go to find hope?

When I’m seeking hope, I like to take myself out of the context of my environment, because the context of my environment always feels heavy and burdened by whatever hopelessness is bumming me out. So I tend to just get in a car and go somewhere. That’s why people like to travel during a breakup or after a breakup or during a grief process. You plan for some escape. I remember planning to go see Lucinda Williams as I was taking care of my dying dog. I was like, “Oh, yeah, I’ll buy these tickets because in two months I know I’ll be sad and I’ll want to go do something different.” I think hope is always saddled with futurity. We hope for the best. We imagine ourselves in the future. If I’m driving to a place 4 hours away, 6 hours away, 12, 15 hours away, I know I’ll feel different when I arrive than how I’m feeling right now. For me, it has always just been hard to find hope in the present. I find hope in the not right now, in an imagined different place.

What is the best advice you have ever received?

Just take a breath, take a minute, take a time out. Not everything has to be decided in the here and now. Unless you have to call 911 and get an ambulance, not everything requires urgent action.

What makes you laugh?

I appreciate the absurd. I saw Bottoms a few weeks ago–I thought it was very genre-defying and really pushed the envelope. My dog makes me laugh in the sense that he’s very smart and he’s very big. So if I ask him if he wants a snack, he’ll just get on his hind legs and jump–I think it’s hilarious. The fiction of Sam Lipsyte makes me laugh. Gatekeepers make me laugh–the insane way people try to keep power. The fact that we all have to pay back our student loans makes me laugh; I have to laugh to keep myself from crying. My friends are really funny. My mom is hilarious: she’s an 80-something-year-old Salvadoran immigrant who’s had her fair share of violence and trauma, but, man, the deadpan is alive and well, and I feel like I get my humor from her.

What else makes me laugh? I think just making light of our shadow selves. I think the shadow self is a space to interrogate, humorously. This is why our most loved comedians aren’t just clowns–they’re Satan’s minions. They just go into the shadowy parts of the underworld of the self and battle their demons right in front of our eyes. And bless them, we’re just like, “Oh, thank you so much for saying the thing I didn’t even know how to access.”

How would you like to be remembered?

As a cult classic? (laughs) I want to be a shelter for people who are genuine outsiders, who struggle with authority and with being true to themselves in light of the many pressing demands of their impacted communities or their failing school systems. So maybe I’d like to be remembered as an icon of the underground.

Brown Neon is available for purchase here.

Artists acknowledge the moments of transformation

In Conversation with Raquel Gutiérrez

Billy Lezra

photo credit: Thea Quiray Tagle

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Raquel Gutiérrez is a critic, essayist, poet, performer, and educator. Gutiérrez’s first book Brown Neon (Coffee House Press) was named as one of the best books of 2022 by The New Yorker and listed in The Best Art Books of 2022 by Hyperallergic. Brown Neon was a Finalist for the Lambda Literary Prize for Best Lesbian Biography/Memoir, a Finalist for the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses’ Firework Award in Creative Nonfiction and Recipient of The Publishing Triangle Judy Grahn Award for Lesbian Nonfiction. A 2021 recipient of the Rabkin Prize in Arts Journalism, as well as a 2017 recipient of The Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant, Gutiérrez teaches in the Oregon State University-Cascades Low Residency Creative Writing MFA Program, as well as for The Institute of American Indian Arts’s (IAIA) Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing program. Gutiérrez gets to call Tucson, Arizona home.

Follow Raquel on Twitter.

In Brown Neon you write: “You need a lot to make a stable foundation, to build walls capable of holding difficult truths.” Although this line is in reference to making adobe, it reminded me of the act of writing. As you write, how do you go about building walls capable of holding difficult truths?

That’s a really powerful question. It’s one thing to write and then there’s another element of writing that involves meaning-making and co-authoring meaning with your reader. So writing is always this process, this act of faith. When you write something, you’re having a conversation with an imagined reader, and then that conversation gets corroborated by your editor, who is a much-needed guard at the post of legibility and comprehension. So once the work passes the editor and reaches the reader’s hands, you hope that you’re able to meet the reader where the reader is at, and that the reader is able to meet you where you’re at. When it comes to building walls, a foundation, you’re creating something that you can back up with a sense of your imagination, the imaginary, your lineages and influences, your vantage point, and the way in which the culture conditions your experience of it. You just write with hopes that you’re able to communicate these threads around culture and politics and the lyric, which all come together to maybe help launch someone into activation. I always struggle with this idea of, “Is it interesting?” But then I’m like, “Well, who’s my imagined audience?” or “Who’s my imagined chorus of disapproval?” And it’s always somebody situated in some sort of coastal metropole. And I’m just like, “Oh, well, no, we’re just going to have to challenge them and hope that they allow themselves to stretch.” I guess the stability of building these walls comes from finding an unshakable sense of self and purpose because it’s so easy to just stop writing.

What qualities does your ideal editor have?

My ideal editor has a light touch, a breadth of understanding, and a diversity of context. They are someone who has read outside of the established canons, someone who’s just like: “I’ve never read that before. I’ve never seen that before on the page,” but trusts the innovative impulse.

In Brown Neon you reference the Anzaldúan concept of nepantla– “the space in between, the locus and sign of transition, the place/space where realities interact and imaginative shifts happen.” When did you first start exploring this space?

Since birth. Since I stepped out of my parents’ house into a public space and realized that what happens in the domestic space is at odds with what happens in these shared collective public spaces that are governed by laws that seem to just stop at your doorstep. When you’re a child of immigrants and you’re brought or born into a new context, you’re a witness to the tensions and struggles and bureaucratic violences the governing figures in your life are dealing with. I think taking that into account at a very fundamental level is how I’ve been introduced to these dialectical moments of like, “Oh, these are two entities with varying power differentials encountering one another.” And that encounter produces a thing, a change. And these power differentials come and go, depending on where you’re at and who’s in the room with you. And so once you step out into the world on your own, you experience authority figures in different ways. There’s a constant flux: nothing is really fixed.

Would you speak about the presence of intertextuality in your work?

The intertextual impulse in my book has always been present in the sense that when you’re writing, you always have other writers’ voices in your head. You’re always moved by somebody else’s language in your mind, in your mouth, until you’re able to find the language for yourself. Someone’s providing you with language, especially if you’re writing about yourself or writing about whatever cultural quandaries and entanglements you’re a part of or adjacent to. You’re always writing from a prism that is refracting the other cultural artifacts that stayed on you or with you in your energetic field. So in a sense, intertextuality is getting these cues for how to live on your terms of engagement. And as you mature as a writer, you’re like, “Okay, let me just turn the volume down on that so that I can focus on turning the volume up on my own voice and hear how I would craft my own syntax.”

What was the process of taking these stand-alone essays and turning them into a book-length project?

When you’re writing for whatever range of platforms that appeal to your aesthetics, politics, and political commitments, you’re adhering to the creative editorial mandates of the magazine or publication. As I was writing my essays, I realized that there were connections and threads that served as connective tissue for a book project, a book-reading experience. So then I started writing for that experience. It’s kind of like putting on a curatorial hat, and thinking about the experience you want the reader to have when they come and spend their precious time with you. You’re offering anywhere between 7 to 15 hours on a text, and you want to give the reader a cohesive experience, a trip, a journey, a beginning to an end. I started with the end of a mentor’s life–death is this powerful occasion for unmooring. My mentor’s death marked the end of my relationship with her in her living embodiment, and the end of my relationship with Southern California. So I took that grief and animated my experience of living in the desert, trying to find community, making sense of heartbreak, mourning, loss, and starting this new life. And then I explored what the desert offered and meant on a literary level, an artistic level, on a queer level. So I just took my chisel and chipped away at this slab of marble until La Pietà revealed itself to me, my own La Pietà.

How do you know when a piece of work is finished?

I know that it’s finished if I feel okay enough with it, and it meets the deadline. Maybe one day I will have the luxury of time and just be like, “Oh my God, I’m so glad I waited those extra three months for that final brushstroke, that final flourish because it came when it came.” I wish I had to worry less about making ends meet and just be able to focus on syntax, on just getting better. I wish I had more time.

Would you speak about the relationship between being in community and being an artist?

I think we’re drawn to community because we have a set of values that we either are familiar with, we know about, we’ve consciously chosen, or maybe that we’re resistant to. Maybe family is a value that you have, but you’re a radical queer, and you’re just like, “No, family is not a value for me.” And you find ways to contradict or corroborate this value through the choices you make in the communities that you decide you want to be a part of, or drive by, drive through, flirt with, consider. So community is there, I think, to help you test drive your values.

You write this question: “Was I destined to enact my own chaos that comes with the territory of being an artist?” I was intrigued by the use of the word chaos–in the Greek etymology chaos is defined as the abyss or emptiness that existed before things came into being. For you, what is the relationship between being an artist and approaching the abyss?

I appreciate you going into that etymologically–the abyss and the unpredictability of chaos. Most people in my position would have gone into engineering, medicine, the stability careers. I went back to school late. Had I gone to college right out of high school, I would have just barely made it. My tuition would have been okay, I wouldn’t have needed to take out loans. But the way that predatory lending played out made it impossible to imagine the promise of “Hey, you go to school, you get your degree, you’ll get a good entry-level job” and all of the things that come with natural ascension in the workforce. All of that is an abyss. That’s chaos. That was unpredictable. I went in there thinking I was going to be a middle manager of this nonprofit organization and be making at least 60K in 2002. And that didn’t happen. So economics demanded something else from a college-educated workforce. When you give me chaos on a platter, that’s kind of where my mind goes; the chaos of trying to eke out a life from some sort of creative field was challenging and hard and sad and heartbreaking because there comes a point where you can’t be too creative.

In an interview you said: “There are many approaches to pain. Are you in it? Are you beside it? Are you with it? I think the prepositional dynamic is an interesting mode of entry into your pain because it just makes you slow down with it.” What is the relationship between writing, the process of documenting, and pain?

The occasion that makes people sit down and bang out a draft of a manuscript is often grief. When you lose someone very close to you, which is the classic example of grief–losing your dad or mom or your partner or your animal friend–there’s a spiritual pain that comes from the finality of their absence and the fact that you’ll never see them again in their human or material form. That’s a really hard fact of life, and it shows you what you’re made of. And a lot of people are able to come to the other side of it, but a lot of people are not. A lot of people self-medicate or enact suicide in small increments in the sense that you’re just like, “Well, I’m going to keep hurting myself today.” I think the reason we need artists and writers so badly is because they’re able to provide us with some language for mourning beautifully, some language for mourning simply, some language for mourning immediately, some relief. That’s the Mount Everest artists and writers are scaling for people who are unable to do that for themselves. A lot of people don’t know how to make language. When I teach an introduction to poetry class, I always try to coax students to think about, like, “Hey, one day you’re going to have to make a toast at a wedding. One day you’re going to have to write a eulogy at a funeral. One day a baby is going to come into your family’s life and it would be nice to have some language ready for these arrivals and departures.” I think poets and artists are there to acknowledge the moment of transformation. This is why we have dirges. This is why we have elegies. This is why we have ballads, sonnets. Somebody inspired this. And pain is something we can gather around for, if we are lucky.

Where do you go to find hope?

When I’m seeking hope, I like to take myself out of the context of my environment, because the context of my environment always feels heavy and burdened by whatever hopelessness is bumming me out. So I tend to just get in a car and go somewhere. That’s why people like to travel during a breakup or after a breakup or during a grief process. You plan for some escape. I remember planning to go see Lucinda Williams as I was taking care of my dying dog. I was like, “Oh, yeah, I’ll buy these tickets because in two months I know I’ll be sad and I’ll want to go do something different.” I think hope is always saddled with futurity. We hope for the best. We imagine ourselves in the future. If I’m driving to a place 4 hours away, 6 hours away, 12, 15 hours away, I know I’ll feel different when I arrive than how I’m feeling right now. For me, it has always just been hard to find hope in the present. I find hope in the not right now, in an imagined different place.

What is the best advice you have ever received?

Just take a breath, take a minute, take a time out. Not everything has to be decided in the here and now. Unless you have to call 911 and get an ambulance, not everything requires urgent action.

What makes you laugh?

I appreciate the absurd. I saw Bottoms a few weeks ago–I thought it was very genre-defying and really pushed the envelope. My dog makes me laugh in the sense that he’s very smart and he’s very big. So if I ask him if he wants a snack, he’ll just get on his hind legs and jump–I think it’s hilarious. The fiction of Sam Lipsyte makes me laugh. Gatekeepers make me laugh–the insane way people try to keep power. The fact that we all have to pay back our student loans makes me laugh; I have to laugh to keep myself from crying. My friends are really funny. My mom is hilarious: she’s an 80-something-year-old Salvadoran immigrant who’s had her fair share of violence and trauma, but, man, the deadpan is alive and well, and I feel like I get my humor from her.

What else makes me laugh? I think just making light of our shadow selves. I think the shadow self is a space to interrogate, humorously. This is why our most loved comedians aren’t just clowns–they’re Satan’s minions. They just go into the shadowy parts of the underworld of the self and battle their demons right in front of our eyes. And bless them, we’re just like, “Oh, thank you so much for saying the thing I didn’t even know how to access.”

How would you like to be remembered?

As a cult classic? (laughs) I want to be a shelter for people who are genuine outsiders, who struggle with authority and with being true to themselves in light of the many pressing demands of their impacted communities or their failing school systems. So maybe I’d like to be remembered as an icon of the underground.