Toward the infinitesimal

In Conversation with Kai Coggin, Part II

Billy Lezra

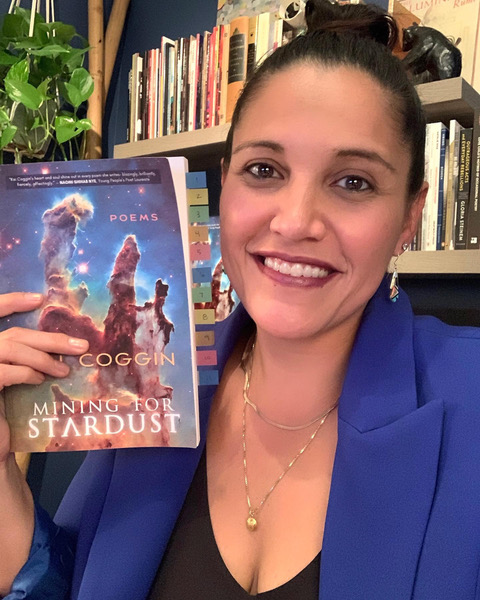

photos by Kai Coggin

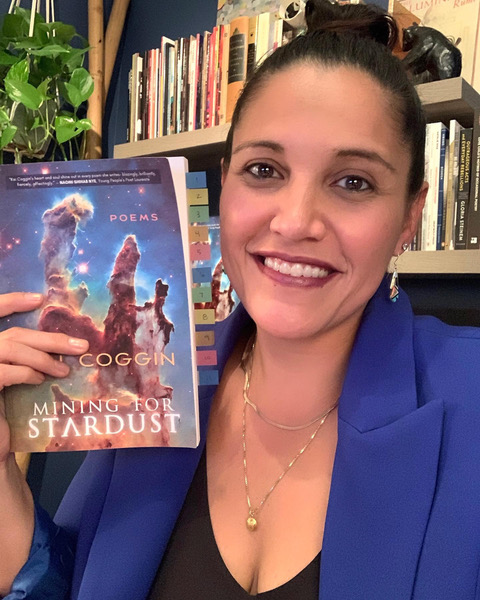

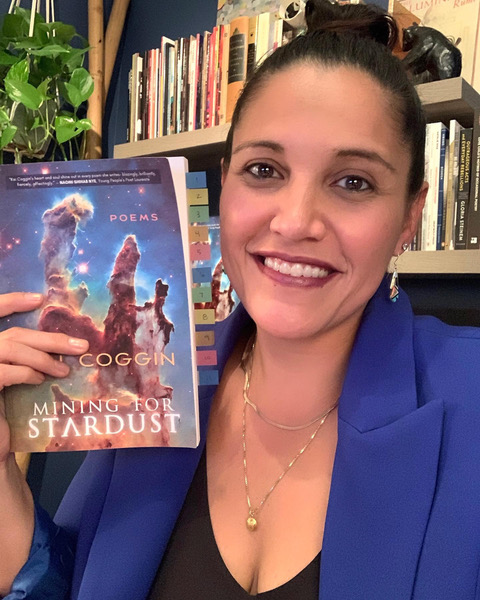

Kai Coggin is the author of MINING FOR STARDUST (FlowerSong Press 2021), INCANDESCENT (Sibling Rivalry Press 2019), WINGSPAN (Golden Dragonfly Press 2016), and PERISCOPE HEART (Swimming with Elephants Publications 2014), as well as a spoken word album SILHOUETTE (2017). She is a queer woman of color who thinks Black Lives Matter, a teaching artist in poetry with the Arkansas Arts Council, and the host of the longest-running consecutive weekly open mic series in the country—Wednesday Night Poetry. Recently awarded the 2021 Governor’s Arts Award and named “Best Poet in Arkansas” by the Arkansas Times, her fierce and powerful poetry has been nominated four times for The Pushcart Prize, as well as Bettering American Poetry 2015, and Best of the Net 2016, 2018, 2021– awarded in 2022. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in POETRY, Cultural Weekly, SOLSTICE, Bellevue Literary Review, Entropy, SWWIM, Split This Rock, Sinister Wisdom, Lavender Review, Luna Luna, Blue Heron Review, Tupelo Press, West Trestle Review, and elsewhere. Coggin is Associate Editor at The Rise Up Review. She lives with her wife and their two adorable dogs in the valley of a small mountain in Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas. Her most recent collection, MINING FOR STARDUST, is available here.

Website | Instagram @skailight | Facebook @kaicoggin

Two years ago the world as we understood it had just stopped and we were all in the process of losing and gaining our bearings. On a cold March day, Kai Coggin appeared on my Facebook screen, dressed in blue, right hand raised, as if prepared to cast an oath, the oath being solace. “In case you are out there and you are going through this alone, I want to do this for you.” With these words she invited viewers across the world to touch her hand, as she opened a virtual installment of Wednesday Night Poetry– a weekly event that hasn’t missed a single week since February 1, 1989, come snow, floods, or city-wide blackouts.

Curious and enlivened, I wrote to Kai. Our subsequent conversation touched on politics, poetry, teaching, and nature.

As the pandemic raged and tore, as fear and grief mounted, Kai’s work and leadership served as a beacon, a reminder that “poetry is a safe place for our feelings,” which are the words she shares with young poets in classrooms all over Arkansas.

Two years since we first crossed paths Kai and I met again to discuss her new book, the intricate incantation: MINING FOR STARDUST.

One of the things that stood out to me about your most recent collection, MINING FOR STARDUST, is how it is a love letter to the natural world, how you dwell on these granular, beautiful details of the water and the light and the flowers. How did your relationship with nature develop?

I was a city dweller before coming to Hot Springs. Born in Bangkok, which was all city and traffic and heat. Houston, too, was a concrete jungle, spread out and tamed. Everything was paved. There were little parks that you could go to if you wanted to see a tree or sit in some grass, sure, but that just wasn’t my way of living. We were poor growing up. We stayed in our apartment complex and played touch football in the parking lot dodging cars. I never thought about nature much. My mother had planted on our balcony, dozens of plants, but I never paid much attention, because I think I was so busy just surviving.

It was so different, coming here, a completely new existence. There are three million acres of protected national forest in Arkansas, where I live. Three million acres. It is called “the natural state.” And I live specifically in Hot Springs National Park, AR, which sits in the Ouachita Mountains, located on constantly percolating 4,000-year-old geothermal spring water, bubbling up at 143 degrees. We drink it. Nature and its magic surround me on all sides now, it is inside me.

I can look out my window at any time and get away from what’s going on in the world. I’m in a valley of trees. There is freshwater. There is a freshwater pond I can swim in right outside my window, and no one will see me. How can I not reflect that in my work? It’s everything around me.

Also, my wife, Joann, is a Master Naturalist. She’s cultivated a literal wildlife sanctuary around us. We have an official plaque from the government that names it as such. Birds and wildlife can safely have their babies here. We have water, protection, and sheltering trees. We leave the lights off outside at night so the birds aren’t bothered. Love of nature is so much more who we are than any kind of conscious act, at this point.

It seems like, over the years, my focus has been getting closer and closer, zooming more microscopically toward the infinitesimal, because it has the infinite in it.

Last July, I wrote poems about the tiniest things, like the pollen that collects on the honeybees’ thighs; they have these little golden saddles. I zoom in because sometimes when I look at the bigger picture of the world… it’s just too much. But I can still find hope and continuity and purpose in these tiny things that are happening, despite what we, as humans, are doing. At what we are destroying. The honeybee continues, the butterflies continue. This year I watched tiny green caterpillars gorge themselves on milkweed, protected them over weeks, and sat in a tent as thirteen monarchs each emerged from their perfectly jeweled chrysalis.

When I put a poem about a hummingbird next to a protest poem, it’s about trying to build a bridge between them. The tiniest most beautiful seedling versus the 100,000 people that died today from COVID. It’s how I cope, how I make meaning. Survive.

How has your relationship with death and hope changed in this last year?

We lost our dear friend Beatriz to COVID because of a lack of access to vaccines. It was at the beginning of 2021. She was staying safe and isolated the whole time. She had a fall and broke her middle finger and had to go get a cast. She caught COVID at the doctor’s office and passed away not long after. Poetically, she died with her middle finger up.

It was unfair because it was an issue of access. Yet here in America, half the population chose negligence. They chose not to help. They chose not to get us out of this. It was and still is absolutely maddening.

I took it upon myself to write through it.

My relationship with death became that I had to name it, and write it.

In those early days of the pandemic, and since, I didn’t want all those people to have died in vain. I didn’t want them to have died just as numbers, because every day the numbers went up (and are still). They are more than just an uptick enumeration of loss. These are people’s parents, grandparents, children, and partners. They each had such exact intricacies and eccentricities about who they were as individuals, who they were as complete people, their likes and dislikes, how their voices sounded, what they cooked, their favorite songs, and what made them laugh.

Writing was an effort to try to humanize the dehumanization of their death. In the cruelty of those days, these souls became piles of body bags that didn’t have room to be buried. They became people who didn’t get to say goodbye to their families, who died alone in the ICU. I wrote about them. For them. I wrote a living archive of what we collectively went through.

Something that LIVED on.

Your book begins with a quote that says, “Pick a flower on Earth, and you move the farthest star.” The last words are, “let’s form a constellation.” What do stars mean to you?

I love that you noticed the first and last. You always show such attention to detail.

Stars are incomprehensible light reaching us here on Earth. They live for a billion years. They are not dead or dying like poets love to say. The stars we can see with our eyes are alive. So it gives me hope, this beauty of the infinite that I don’t necessarily have to understand. That’s what stars do. That’s what the planets do. The title poem of the book was written on the night of grand conjunction, the night of the 2020 winter solstice. Joann and I are very much into cosmic occurrences and meteor showers. She always takes me outside, makes a tent piled up with pillows and blankets, and we build a fire and watch the stars. Again, this was something I never had when I was in the city, a window she opened for me with her beautiful spontaneity. So there’s a literal love and appreciation for looking up and reaching for light that’s trying to reach us.

There’s also the concept of light in the darkness, little pinpricks of hope in the abyss. Only those who walk in the dark can see the stars. A candle burns brightest when it’s dark. All of these little quotes that I can remember from growing to uphold me in that space of hope. Our little existence here on earth is so small in the realm of everything that’s going on. I am one little tiny atom in a universe that’s all around us, insignificant, yet a part of the oneness of everything– that paradox alone blows my mind. I love being awestruck. I love not having words for things. I love being just completely dumbfounded by beauty or awe or wonder. These days, in order to survive, I really have to lean into that wonder, into being mystified.

When was the last time wonder left you speechless?

We went to this gorgeous dark sky campsite on the Buffalo River, where they turn off all the lights for miles around it seems, so you can see the Milky Way and all the stars. We were sitting on the trunk of the car, looking at this wall of trees, and suddenly thousands of tiny lights started twinkling. I mean thousands, and it was like all the trees were shimmering, glittering with some ethereal sparkling. And then, in a flash, all the twinkling lights rose up into the sky– it was fireflies! Fireflies rising up into millions of stars. Our eyes couldn’t tell the difference between the fireflies and the twinkling stars.

Then we kissed.

That’s the nourishment my soul needs. I can go back to that moment and feel the magic of the universe, feel loved, and held by something bigger, something divine. So many people don’t get to see things like that. They can’t stop their hectic lives long enough to slow down and see. So I write about it, even if I can’t encapsulate what it really, truly was like. I try. I’ll keep trying to give words to the incomprehensible beauty of moments like these.

The poem Not Enough Words for Light is about that glimmering night.

In the poem Essence, you write: “if only we trusted our own essence from birth / knew the transformations to come / were all part of the becoming— / that we had the imprint all along.”

How do you formulate that trust that you’re describing, and the hope?

It’s hard. We have to stretch, especially now, to look for and find commonalities. But what else is there but to keep reaching? I’d rather reach than not.

It’s the concept of the soul you’re striving toward. Your soul, the perfection of the soul from which you come. You already are perfect. But you’re going through this human experience and all of this pain and struggle and trauma to learn lessons. You’re that little seed that gets dropped into the dirt, into the mud, into the muck of everything. You ALREADY ARE everything that you’re going to be. Your essence is Divine. You just have to go through the process of remembering and becoming that.

We aren’t struggling for nothing. We aren’t suffering for nothing. There is perfection, enlightenment, and peace that could be attained even when we were little, even when we were just born. For me, that was hard to fathom, and hard to own, because my little seed was planted in some traumatic and dangerous gardens before this one.

But it was all a lesson. All learning. All growing and healing. All a building of tools and experiences I could use to help others.

In MINING FOR STARDUST, how did you decide to include the final blank page for the reader to write in?

I was putting together the end of the manuscript, and I saw how valuable it was for me to have the space to process what we had been through– this book. As a teaching artist, I hold space for my students to express their feelings. My mantra in the classroom is: “poetry is a safe place for your feelings.”

I wanted my readers to feel safe, too, somehow, especially after recalling the traumatic time to which this book speaks. A reader, for me, is someone who is influenced by my thoughts and words. Even if it’s only during the time they take to read my book– I’m holding them with my words, with my intention, with my heart.

They might just trudge on after the last page of the book, and go on with their day. That’s what capitalism trains us to do. We just keep trudging. But with that blank page, I am here to say: “Take this piece of paper and fill it up with what you’re feeling right now.”

Sometimes permission or agency to do something like that is all it takes to open someone’s flood gates. We hold so much inside, yet people wouldn’t normally just decide, “I’m going to go write in my journal after reading this book.”

I wanted to intentionally make space for my readers because I want them to be in my constellation. We are all a part of each other. We went through this time collectively as a human race. Be a part of my book. What did you feel through this? Who did you lose? What did you experience? Tell me. Write it here. Let go. Open. Heal.

One of my favorite questions that you ask is: “What do you take with you into tomorrow?”

What do you take with you into tomorrow?

Gratitude. It’s a conscious decision for me as a writer to reflect not only my inner world, but to reflect the outer world and speak about injustices and speak about atrocities and things that need to be named and to still have hope and believe in Beauty, Truth, and Light. I live in a space of gratitude for those in my inner world who hold my spirit, nourish my heart, and protect my soul.

I know it’s easy to stay in a dark place because I’ve lived there, and spent most of my twenties cut off from my own light. I made a home in the dark for a long time. Now, I have the creative tools to help someone out of that darkness. Even in the most difficult times, we can all find the light, little pinpricks of hope… we can use our tools, to dig deeper, to mine for stardust.

MINING FOR STARDUST is available for purchase here.

Toward the infinitesimal

In Conversation with Kai Coggin, Part II

Billy Lezra

photos by Kai Coggin

Kai Coggin is the author of MINING FOR STARDUST (FlowerSong Press 2021), INCANDESCENT (Sibling Rivalry Press 2019), WINGSPAN (Golden Dragonfly Press 2016), and PERISCOPE HEART (Swimming with Elephants Publications 2014), as well as a spoken word album SILHOUETTE (2017). She is a queer woman of color who thinks Black Lives Matter, a teaching artist in poetry with the Arkansas Arts Council, and the host of the longest-running consecutive weekly open mic series in the country—Wednesday Night Poetry. Recently awarded the 2021 Governor’s Arts Award and named “Best Poet in Arkansas” by the Arkansas Times, her fierce and powerful poetry has been nominated four times for The Pushcart Prize, as well as Bettering American Poetry 2015, and Best of the Net 2016, 2018, 2021– awarded in 2022. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in POETRY, Cultural Weekly, SOLSTICE, Bellevue Literary Review, Entropy, SWWIM, Split This Rock, Sinister Wisdom, Lavender Review, Luna Luna, Blue Heron Review, Tupelo Press, West Trestle Review, and elsewhere. Coggin is Associate Editor at The Rise Up Review. She lives with her wife and their two adorable dogs in the valley of a small mountain in Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas. Her most recent collection, MINING FOR STARDUST, is available here.

Website | Instagram @skailight | Facebook @kaicoggin

Two years ago the world as we understood it had just stopped and we were all in the process of losing and gaining our bearings. On a cold March day, Kai Coggin appeared on my Facebook screen, dressed in blue, right hand raised, as if prepared to cast an oath, the oath being solace. “In case you are out there and you are going through this alone, I want to do this for you.” With these words she invited viewers across the world to touch her hand, as she opened a virtual installment of Wednesday Night Poetry– a weekly event that hasn’t missed a single week since February 1, 1989, come snow, floods, or city-wide blackouts.

Curious and enlivened, I wrote to Kai. Our subsequent conversation touched on politics, poetry, teaching, and nature.

As the pandemic raged and tore, as fear and grief mounted, Kai’s work and leadership served as a beacon, a reminder that “poetry is a safe place for our feelings,” which are the words she shares with young poets in classrooms all over Arkansas.

Two years since we first crossed paths Kai and I met again to discuss her new book, the intricate incantation: MINING FOR STARDUST.

One of the things that stood out to me about your most recent collection, MINING FOR STARDUST, is how it is a love letter to the natural world, how you dwell on these granular, beautiful details of the water and the light and the flowers. How did your relationship with nature develop?

I was a city dweller before coming to Hot Springs. Born in Bangkok, which was all city and traffic and heat. Houston, too, was a concrete jungle, spread out and tamed. Everything was paved. There were little parks that you could go to if you wanted to see a tree or sit in some grass, sure, but that just wasn’t my way of living. We were poor growing up. We stayed in our apartment complex and played touch football in the parking lot dodging cars. I never thought about nature much. My mother had planted on our balcony, dozens of plants, but I never paid much attention, because I think I was so busy just surviving.

It was so different, coming here, a completely new existence. There are three million acres of protected national forest in Arkansas, where I live. Three million acres. It is called “the natural state.” And I live specifically in Hot Springs National Park, AR, which sits in the Ouachita Mountains, located on constantly percolating 4,000-year-old geothermal spring water, bubbling up at 143 degrees. We drink it. Nature and its magic surround me on all sides now, it is inside me.

I can look out my window at any time and get away from what’s going on in the world. I’m in a valley of trees. There is freshwater. There is a freshwater pond I can swim in right outside my window, and no one will see me. How can I not reflect that in my work? It’s everything around me.

Also, my wife, Joann, is a Master Naturalist. She’s cultivated a literal wildlife sanctuary around us. We have an official plaque from the government that names it as such. Birds and wildlife can safely have their babies here. We have water, protection, and sheltering trees. We leave the lights off outside at night so the birds aren’t bothered. Love of nature is so much more who we are than any kind of conscious act, at this point.

It seems like, over the years, my focus has been getting closer and closer, zooming more microscopically toward the infinitesimal, because it has the infinite in it.

Last July, I wrote poems about the tiniest things, like the pollen that collects on the honeybees’ thighs; they have these little golden saddles. I zoom in because sometimes when I look at the bigger picture of the world… it’s just too much. But I can still find hope and continuity and purpose in these tiny things that are happening, despite what we, as humans, are doing. At what we are destroying. The honeybee continues, the butterflies continue. This year I watched tiny green caterpillars gorge themselves on milkweed, protected them over weeks, and sat in a tent as thirteen monarchs each emerged from their perfectly jeweled chrysalis.

When I put a poem about a hummingbird next to a protest poem, it’s about trying to build a bridge between them. The tiniest most beautiful seedling versus the 100,000 people that died today from COVID. It’s how I cope, how I make meaning. Survive.

How has your relationship with death and hope changed in this last year?

We lost our dear friend Beatriz to COVID because of a lack of access to vaccines. It was at the beginning of 2021. She was staying safe and isolated the whole time. She had a fall and broke her middle finger and had to go get a cast. She caught COVID at the doctor’s office and passed away not long after. Poetically, she died with her middle finger up.

It was unfair because it was an issue of access. Yet here in America, half the population chose negligence. They chose not to help. They chose not to get us out of this. It was and still is absolutely maddening.

I took it upon myself to write through it.

My relationship with death became that I had to name it, and write it.

In those early days of the pandemic, and since, I didn’t want all those people to have died in vain. I didn’t want them to have died just as numbers, because every day the numbers went up (and are still). They are more than just an uptick enumeration of loss. These are people’s parents, grandparents, children, and partners. They each had such exact intricacies and eccentricities about who they were as individuals, who they were as complete people, their likes and dislikes, how their voices sounded, what they cooked, their favorite songs, and what made them laugh.

Writing was an effort to try to humanize the dehumanization of their death. In the cruelty of those days, these souls became piles of body bags that didn’t have room to be buried. They became people who didn’t get to say goodbye to their families, who died alone in the ICU. I wrote about them. For them. I wrote a living archive of what we collectively went through.

Something that LIVED on.

Your book begins with a quote that says, “Pick a flower on Earth, and you move the farthest star.” The last words are, “let’s form a constellation.” What do stars mean to you?

I love that you noticed the first and last. You always show such attention to detail.

Stars are incomprehensible light reaching us here on Earth. They live for a billion years. They are not dead or dying like poets love to say. The stars we can see with our eyes are alive. So it gives me hope, this beauty of the infinite that I don’t necessarily have to understand. That’s what stars do. That’s what the planets do. The title poem of the book was written on the night of grand conjunction, the night of the 2020 winter solstice. Joann and I are very much into cosmic occurrences and meteor showers. She always takes me outside, makes a tent piled up with pillows and blankets, and we build a fire and watch the stars. Again, this was something I never had when I was in the city, a window she opened for me with her beautiful spontaneity. So there’s a literal love and appreciation for looking up and reaching for light that’s trying to reach us.

There’s also the concept of light in the darkness, little pinpricks of hope in the abyss. Only those who walk in the dark can see the stars. A candle burns brightest when it’s dark. All of these little quotes that I can remember from growing to uphold me in that space of hope. Our little existence here on earth is so small in the realm of everything that’s going on. I am one little tiny atom in a universe that’s all around us, insignificant, yet a part of the oneness of everything– that paradox alone blows my mind. I love being awestruck. I love not having words for things. I love being just completely dumbfounded by beauty or awe or wonder. These days, in order to survive, I really have to lean into that wonder, into being mystified.

When was the last time wonder left you speechless?

We went to this gorgeous dark sky campsite on the Buffalo River, where they turn off all the lights for miles around it seems, so you can see the Milky Way and all the stars. We were sitting on the trunk of the car, looking at this wall of trees, and suddenly thousands of tiny lights started twinkling. I mean thousands, and it was like all the trees were shimmering, glittering with some ethereal sparkling. And then, in a flash, all the twinkling lights rose up into the sky– it was fireflies! Fireflies rising up into millions of stars. Our eyes couldn’t tell the difference between the fireflies and the twinkling stars.

Then we kissed.

That’s the nourishment my soul needs. I can go back to that moment and feel the magic of the universe, feel loved, and held by something bigger, something divine. So many people don’t get to see things like that. They can’t stop their hectic lives long enough to slow down and see. So I write about it, even if I can’t encapsulate what it really, truly was like. I try. I’ll keep trying to give words to the incomprehensible beauty of moments like these.

The poem Not Enough Words for Light is about that glimmering night.

In the poem Essence, you write: “if only we trusted our own essence from birth / knew the transformations to come / were all part of the becoming— / that we had the imprint all along.”

How do you formulate that trust that you’re describing, and the hope?

It’s hard. We have to stretch, especially now, to look for and find commonalities. But what else is there but to keep reaching? I’d rather reach than not.

It’s the concept of the soul you’re striving toward. Your soul, the perfection of the soul from which you come. You already are perfect. But you’re going through this human experience and all of this pain and struggle and trauma to learn lessons. You’re that little seed that gets dropped into the dirt, into the mud, into the muck of everything. You ALREADY ARE everything that you’re going to be. Your essence is Divine. You just have to go through the process of remembering and becoming that.

We aren’t struggling for nothing. We aren’t suffering for nothing. There is perfection, enlightenment, and peace that could be attained even when we were little, even when we were just born. For me, that was hard to fathom, and hard to own, because my little seed was planted in some traumatic and dangerous gardens before this one.

But it was all a lesson. All learning. All growing and healing. All a building of tools and experiences I could use to help others.

In MINING FOR STARDUST, how did you decide to include the final blank page for the reader to write in?

I was putting together the end of the manuscript, and I saw how valuable it was for me to have the space to process what we had been through– this book. As a teaching artist, I hold space for my students to express their feelings. My mantra in the classroom is: “poetry is a safe place for your feelings.”

I wanted my readers to feel safe, too, somehow, especially after recalling the traumatic time to which this book speaks. A reader, for me, is someone who is influenced by my thoughts and words. Even if it’s only during the time they take to read my book– I’m holding them with my words, with my intention, with my heart.

They might just trudge on after the last page of the book, and go on with their day. That’s what capitalism trains us to do. We just keep trudging. But with that blank page, I am here to say: “Take this piece of paper and fill it up with what you’re feeling right now.”

Sometimes permission or agency to do something like that is all it takes to open someone’s flood gates. We hold so much inside, yet people wouldn’t normally just decide, “I’m going to go write in my journal after reading this book.”

I wanted to intentionally make space for my readers because I want them to be in my constellation. We are all a part of each other. We went through this time collectively as a human race. Be a part of my book. What did you feel through this? Who did you lose? What did you experience? Tell me. Write it here. Let go. Open. Heal.

One of my favorite questions that you ask is: “What do you take with you into tomorrow?”

What do you take with you into tomorrow?

Gratitude. It’s a conscious decision for me as a writer to reflect not only my inner world, but to reflect the outer world and speak about injustices and speak about atrocities and things that need to be named and to still have hope and believe in Beauty, Truth, and Light. I live in a space of gratitude for those in my inner world who hold my spirit, nourish my heart, and protect my soul.

I know it’s easy to stay in a dark place because I’ve lived there, and spent most of my twenties cut off from my own light. I made a home in the dark for a long time. Now, I have the creative tools to help someone out of that darkness. Even in the most difficult times, we can all find the light, little pinpricks of hope… we can use our tools, to dig deeper, to mine for stardust.

MINING FOR STARDUST is available for purchase here.